As we gaze upon Montreal’s snow blanket in mid-March, let us also fantasize of the spring that is promised to be near with a few verses from a 1814 chapbook titled Day, A Pastoral.

Now the pine-tree’s waving top

Gently greets the morning gale!

Kidlings, now, begin to crop

Daisies in the dewy vale.

By the brook the shepherd dines;

From the fierce meridian heat

Shelter’d by the branching pines,

Pendant o’er his grassy seat.

Now the flock forsakes the glade,

Where uncheck’d the sun-beams fall;

Sure to find a pleasing shade

By the ivy’d abbey wall

Not a leaf has leave to stir,

Nature’s lull’d serene, and still!

Quiet o’er the shepherd’s cur,

Sleeping on the heath-clad hill.

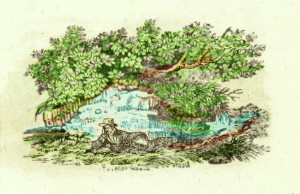

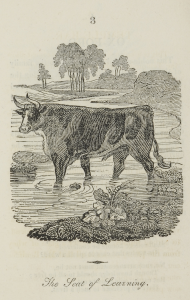

This English Pastoral Poetry was relatively refreshing to encode in the process of The Chapbook Digitization Project — especially in the winter term as it poetically describes the day of a shepherd dependent on nature. Amidst downtown Montreal in it’s coldest days, I am left, unlike the resting shepherd in the image, to ponder on brighter days.

The chapbook’s wood engravings were illustrated by Thomas Bewick without colour. The displayed picture was edited to convey the spring colours that are a product of my imagination 🙂