-

-

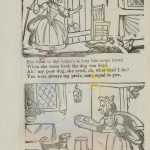

Dumpty Humpty

-

-

When You and I Were Young, Maggie

-

-

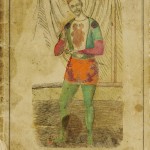

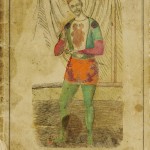

The Clown’s Song Book

Looking for the right thing to say? These stories of love and loss are found in The Clown’s Song Book (published by the Torrey Brothers of 13 Spruce-Street, New York), found in the Sheila R. Bourke Collection of chapbooks.

When You and I were Young, Maggie.

I wandered, to-day, to the hill, Maggie,

To watch the scenes below ;

The creek, and the creaking old mill, Maggie,

As we used to, long ago.

The green grove has gone from the hill, Maggie,

Where first the daisies sprung;

The creaking old mill is still, Maggie,

Since you and I were young!

CHORUS :

And now we are aged and grey, Maggie,

And the trials of life nearly done ;

Let us sing of the days that are gone, Maggie.

When you and I were young !

A city so silent and lone, Maggie,

Where the young and the gay and the best,

In polished white mansions of stone, Maggie,

Have each found a place of rest,

Is built where the birds used to play, Maggie,

And join in the songs that were sung—

For, we sang as gay as they, Maggie,

When you and I were young !

They say I am feeble with age, Maggie,

My steps are less sprightly than then ;

My face is a well-written page, Maggie,

But time alone was the pen !

They say we are aged and grey, Maggie,

As sprays by the white breakers flung ;

But to me you’re as fair as you were, Maggie,

When you and I were young !

Dumpty Humpty.

I’m a proken-hearted Dutchman, A boor old blayed oud Dutchman :

My vife’s she’s vent und gone, Und run avay, und giftf to me der shake.

She’s gone and jined Sorosis, Der Yommen’s Righd’s Sorosis :

Und vile she’s hafing pully dimes, I dink my heart vill preak.

CHORUS :

Oh ! my Dumpty Humpty’s gone oud from my sighd, Und ve mighd hafe peen so habby, yes ve mighd,

Put now she’s gone avay to peen a vommen’s righd, Und I bed dat she’s got a dozen husman’s more.

She vas so nice und poody, So shblendid und so poody—

Ven I married her I nefer dinked, Dat she can use me so.

Pud she’s goned avay und greaved me, Gone righd off und leaved me,

Und now my heart’s dat pusted, I vant you all to know.

Put I must go und find her, Go on der shly und find her,

Bhust go righd up pehind her, Und to her I vill say:

“You dought dat I vas shooken, Pnt you find you are mistooken ;

You can’t fool me, Louisa, ‘Cause I voon’d pe fooled dat vay.”

Now, my friends, took a varning, Led my fade pe a varning ;

Dem vommens dem is all alike, Und I ped you dad its drue.

You can loaf dem and caress dem, Fix dem up und dress dem,

Dey vill bead you if dey got a shance, Und go vay und shook you, too.