By: Pamela Casey

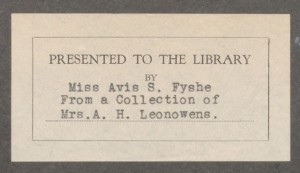

I spent the winter semester in a tucked-away part of Rare Books and Special Collections (RBSC) processing a collection of late 19th-century travel photographs as part of my practicum towards a Master’s in Library and Information Studies. Most of the photographs in the collection are unidentified, but a selection bear signatures of their photographers, including Antonio Beato, Francis Frith, and Samuel Bourne, while others carry donor markings. Recently, a donor name caught the attention of Dr Virr, Head of RBSC and Curator of Manuscripts. While showing him a collection of Cambodian photographs, he recognised one of the names on the donor label. The collection had belonged to Anna Leonowens, of King of Siam fame, a Victorian widow who worked as a governess at the Siamese court in Bangkok, teaching English to the king’s many wives and 87 children from 1862-1868. After a bit of digging, I discovered that Avis S. Fyshe, the actual donor of the photos to the library, was Leonowens’s granddaughter.

Avis Selina Fyshe was born in 1886 near Halifax, Nova Scotia. In 1897, she and her family settled in Montreal, and we know Fyshe attended Royal Victoria College in 1903-1904[1]. After her parents died, Fyshe was her grandmother’s caregiver after her stroke until her death in 1915[2]. Later, Fyshe lived abroad and became an artist. She studied art at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, as well as illumination and lettering in England, Germany and France. In 1933 she was back in Montreal, where she was active in the Montreal and Canadian artist communities and designed bookplates and Christmas cards[3].

“Bas relief along the corridors of Nakhon Wat, representing scenes from the Hindu Epic Rāmăyānă; the work of early Buddha missionaries to Cambodia”, John Thomson, 1866

It was Fyshe who provided author Margaret Landon with the material to write her 1944 bestseller, Anna and the King of Siam. Fyshe had been attempting to write her own book on her “fabulous grandmother,” but this had not been going well[4]. After a chance meeting in 1939, Fyshe gave to Landon her draft biography, all 200-typed pages of it, along with family letters and other papers. Landon used the material to write the hugely popular semi-fictional biography of Anna, a book that went on to inspire a famous Rodgers and Hammerstein musical and numerous film adaptations.

So what of the photos? Wonderfully, these are signed by their photographer: John Thomson, a Scotsman, and the first to photograph Angkor Wat in 1866. In 1867, Thomson published a book of his photographs of the temple ruins, The Antiquities of Cambodia: A series of photographs taken on the spot. In his introduction, he describes how he was inspired to make the arduous journey after reading Henri Mouhot’s writings about the site. Thomson travelled with all the “photographic apparatus and chemicals necessary for the wet collodion process”:

At Kabin we left our boats to begin a weary overland journey, lasting nearly a month, and completely exhausting our stock of provisions and our strength. About ten days before we reached our destination, I had an attack of jungle fever, which left me so weak that I was for some time unable to walk… Our mode of travel varied according to circumstances…ponies harnessed in the rudest fashion, buffalo waggons that were continually breaking down, and being repaired with the materials which the forest or jungle might supply, causing us to halt for hours, not infrequently at midday, in a stunted forest, or on a shelterless prairie, with the vertical rays of a tropical sun beating down upon our heads…[5]

A selection of the vivid results of Thomson’s efforts is now at RBSC, sixteen photographs in all, each mounted on thick white paper and together housed in an old manuscript folder, the orange inner folds of which have stained the top photograph. The photos are all labeled and identified as being Nakhon Wat, the “Temple of the Capital,” known as Angkor Wat[6].

In his book Thomson created a panoramic photo of the temple entrance, and some of our photos seemed to have formed part of it. Many of the RBSC photos are of the temple’s sculptural reliefs depicting key scenes from Rāmăyānă – Rama’s journey – an epic poem composed in Sanskrit about how Rama, with the help of an army of monkeys, battles to save his wife Sita who has been abducted by Ravana. Thomson’s photographs capture the calm and beauty of the place: “Sculptured Devotees”, carvings of the “Bountiful Lady”, an impressive exterior roof view, and the serenely smiling Triple-headed tower or roof of Nakhon Wat.

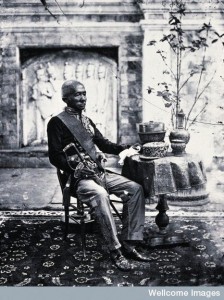

“Part of the roof of Nakhon Wat, with Siamese standing near the entrance to the Buddhists’ sacred Baptismal font”, John Thomson, 1866

Thomson was supported by the King of Siam on his travels, and also famously took his portrait. Thomson’s dates coincide with Leonowens’s time at the Siamese court, so it seems likely that they met. That Leonowens valued Thomson’s photographs is evident from her first book, The English Governess at the Siamese Court, with its prefatory mention of the “able English photographer, James Thomson”[7] (we have no idea how he took to being called English, never mind James), and her use of illustrations that are direct, unattributed copies of his photographs (the title page credits them as “Illustrations, from photographs presented to the author by the King of Siam”)[8]. Where Thomson’s actual photographs appear in her later book, The Romance of the Harem, the photographer is simply left uncredited.

The esteem Leonowens might have held for the able photographer does not appear to have been mutual, judging from the irritable commentary Thomson makes the few times her name pops up in his own writings. “Mrs Leonowens,” Thomson sniffs, referring to her version of the events depicted in a photo he took at the Siamese court, “ought to have known better.” He drily questions her descriptions of Angkor Wat: “From Mrs Leonowens’s account of her expedition…I gather that she must have travelled along the same route as ourselves; but I cannot make out, if that was the case, how her elephants could have ‘pressed on heavily, but almost noiselessly, over a parti-coloured carpet of flowers.’”

“The 1st King of Siam, King Mongkut, in western style state robes, Bangkok, Siam”, John Thomson, 1865-1866. Wellcome Library, London V0037055. http://wellcomeimages.org/ indexplus/image/V0037055.html

The flowers in this jungle, he explains, are extremely rare and highly prized, and so unlikely to have had guides allow them to be trampled. Thomson even suggests that Leonowens’s descriptions of the site were lifted directly from Henri Moulot’s, and he can’t help but interject while quoting from one of Leonowen’s florid descriptions: ‘The Wat stands like a petrified dream of some Michael Angelo [what is a petrified dream?]…”

I am perhaps reading too much between the lines, but I sense a spat between the author of these photographs and their subsequent owner. The two perhaps saw each other as competitors, each determined that their vision and experience of this place, exotic and still largely unknown to the West, should hold sway. Either way, the John Thomson photographs in the RBSC holdings are among the first ever taken of Angkor Wat, one of the world’s most important archeological sites, and wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for Anna Leonowens and Avis Selina Fyshe.

Notes:

[1] McGill University Archives.

[2] Susan Morgan, Bombay Anna: The Real Story and Remarkable Adventures of the King and I Governess (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

[3] Avis Selina Fyshe, National Gallery of Canada Artist Information Form, 1943. Copy sourced at the Canadian Women Artist History Initiative.

[4] Morgan, 214.

[5] John Thomson, The Antiquities of Cambodia. A Series of Photographs Taken on the Spot with Letterpress Description. Edinburgh: Edmonston & Douglas, 1867, p. 7-8.

[6] I have been unable to find information to explain why the name Nakhon Wat was used instead of Angkor Wat.

[7] Anna Harrietta Crawford Leonowens, The English Governess at the Siamese Court: Being Recollections of Six Years in the Royal Palace at Bangkok. Boston: Fields, Osgood & Co., 1870, p. vii.

[8] Leonowens, The English Governess at the Siamese Court: Being Recollections of Six Years in the Royal Palace at Bangkok, first title page.

[9] John Thomson, The Straits of Malacca, Indo-China, and China: or, Ten years’ travels, adventures, and residence abroad. New York: Harper & brothers, 1875, p. 97.

[10] Thomson, Straits, 129.

[11] Thomson, Straits, 130.