AN AMERICAN VOLTAIRE: The J. Patrick Lee Voltaire Collection at McGill

By: Nicholas Cronk, Voltaire Foundation, Oxford University

Published by Cambridge Scholars in 2009, with contributions by Nicholas Cronk and other Voltaire scholars.

Pat Lee, who died in 2006, was a life-enhancing friend as well as a Voltaire enthusiast and an avid collector of books. The J. Patrick Lee Voltaire Collection was acquired by McGill in 2013, and contains some 2000 books and 42 manuscripts, relative to Voltaire and his contemporaries. I recently had the huge pleasure of helping Ann Marie Holland organise in the Rare Books Library a small exhibit containing just a few of the highlights of this collection.

Like any great collection, this one has its share of precious printed books, as well as some remarkable manuscripts, not least a manuscript compilation of verse that belonged to Voltaire’s companion, Emilie Du Châtelet – this last item has been exhibited in Paris at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. The compilation also has its unique personality: Pat Lee, as an American- who loved Voltaire, was born in Kentucky, and wrote his doctorate on Voltaire at Fordham University in New York – clearly had a particular predilection for books by and about Voltaire that were in some way connected with America.

Americans were keen readers of Voltaire from the early years of the Republic, and the provenance of some of the items is startling: a volume of Voltaire that belonged to Theodore Roosevelt, and a manuscript collection of French poetry with the bookplate of … George Washington. But it’s not just the famous names that are interesting. A book called Fame and Fancy, or Voltaire Improved, published in Boston in 1826, provides an American take on Voltaire: but Pat Lee’s copy is also interesting because the bookplate records its American owner: ‘Daniel Green, Jr., Portland, Maine’.

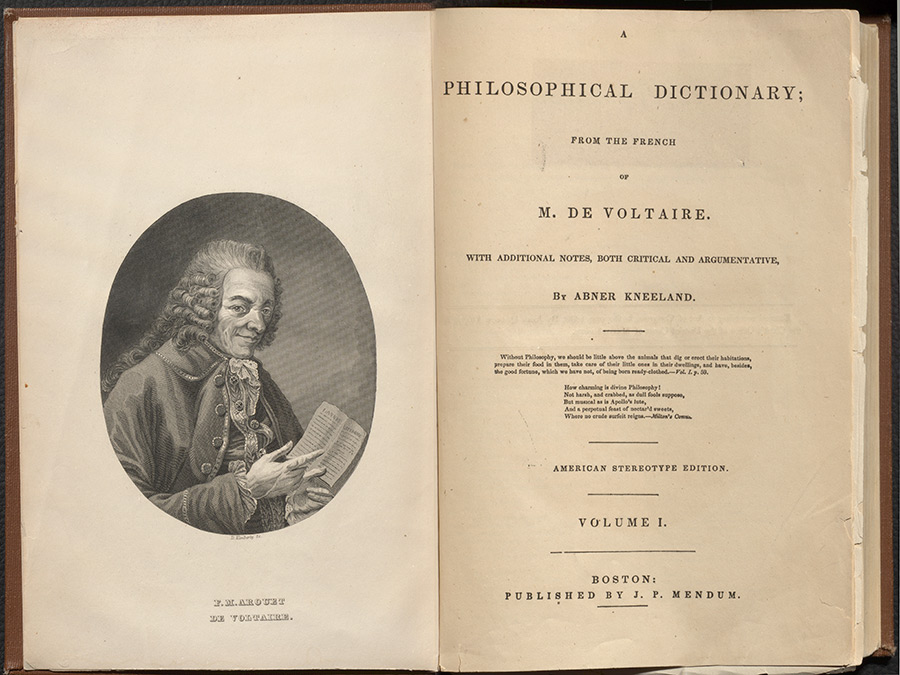

Another remarkable production from the same decade is Abner Kneeland’s translation of Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique, also published in Boston in 1836.  Kneeland (1774-1844) was an evangelist minister of radical views, remembered as the last man jailed in the United States for blasphemy – among his publications are The Deist (1822) and A Review of the Evidences of Christianity (1829). His edition of Voltaire’s Philosophical Dictionary was clearly a polemical gesture therefore, and one of the copies in Pat Lee’s collection is exceptional. The anonymous American owner has inserted two blank sheets in the middle of the volume, with pages headed ‘Births’, ‘Marriages’ and ‘Deaths’. It was common of course for families to own a ‘family Bible’ with such blank pages serving to record key events in a family’s history, a volume that would be handed down from generation to generation. In this (unique?) example, a nineteenth-century American has radically subverted the genre of the ‘family Bible’ by creating a ‘family Voltaire’. Only in America…

Kneeland (1774-1844) was an evangelist minister of radical views, remembered as the last man jailed in the United States for blasphemy – among his publications are The Deist (1822) and A Review of the Evidences of Christianity (1829). His edition of Voltaire’s Philosophical Dictionary was clearly a polemical gesture therefore, and one of the copies in Pat Lee’s collection is exceptional. The anonymous American owner has inserted two blank sheets in the middle of the volume, with pages headed ‘Births’, ‘Marriages’ and ‘Deaths’. It was common of course for families to own a ‘family Bible’ with such blank pages serving to record key events in a family’s history, a volume that would be handed down from generation to generation. In this (unique?) example, a nineteenth-century American has radically subverted the genre of the ‘family Bible’ by creating a ‘family Voltaire’. Only in America…

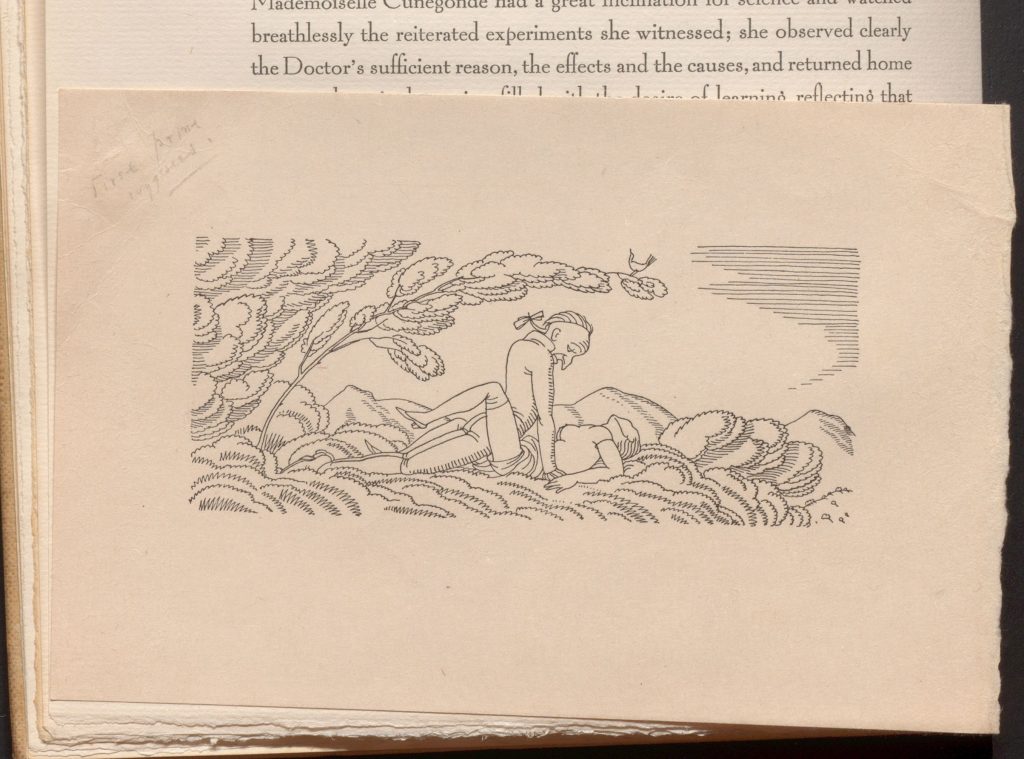

In the twentieth century, New York publishers were active in producing illustrated editions, and there are some remarkable illustrated Candide in this collection. The Rockwell Kent illustrations for Random House (1928) are justly famous – not least because the picture of Voltaire’s house in the colophon went on to become widely familiar as the Random House logo. Rockwell Kent’s first depiction of Pangloss conducting an experiment in natural philosophy in the shrubbery was deemed too shocking, and he had to replace it with a more anodine image:- the first edition in this collection is very special because it includes a real rarity -the ‘censored’ image has been tipped in to cover up its timid replacement.( See also the NYPL Candide website for more on Rockwell Kent)

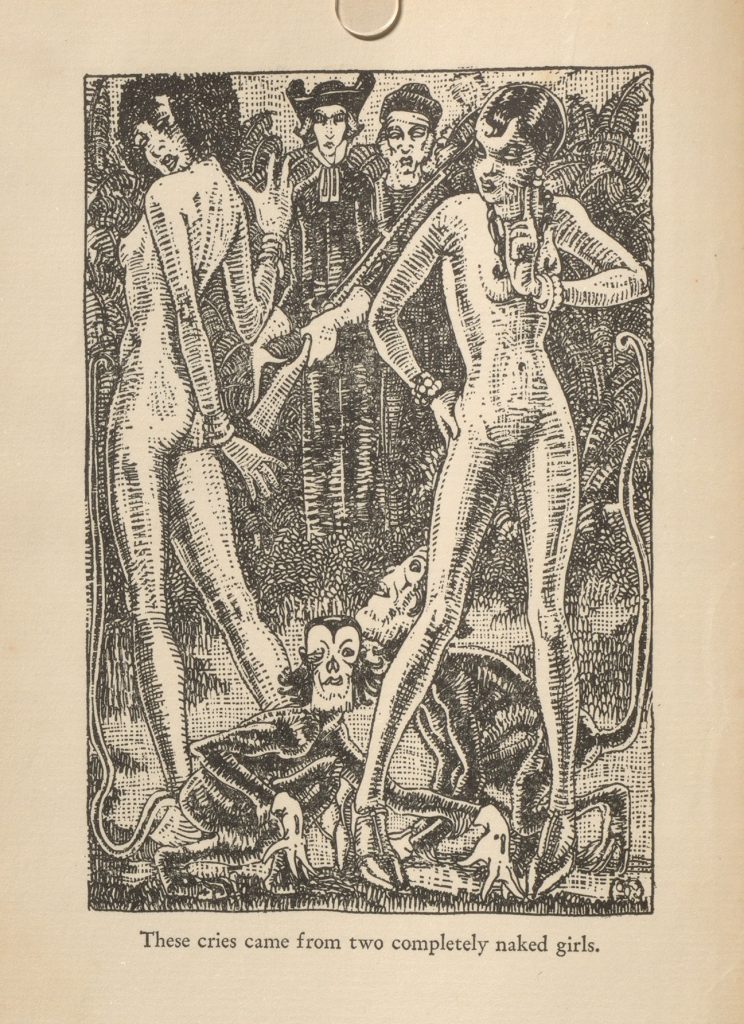

The Rockwell Kent Candide is a celebrated publication, but also remarkable is the fact that the year before, 1927, there had appeared an edition of Candide illustrated by Clara Tice, a bohemian figure known as the Queen of Greenwich Village (below left); and two years later, in 1930, there was an illustrated edition by Mahlon Blane (below right).

This is real testimony to the vibrancy of the American market for illustrated books: three major illustrated editions of Candide all published in New York within the space of four years – and all three in completely contrasting artistic styles.

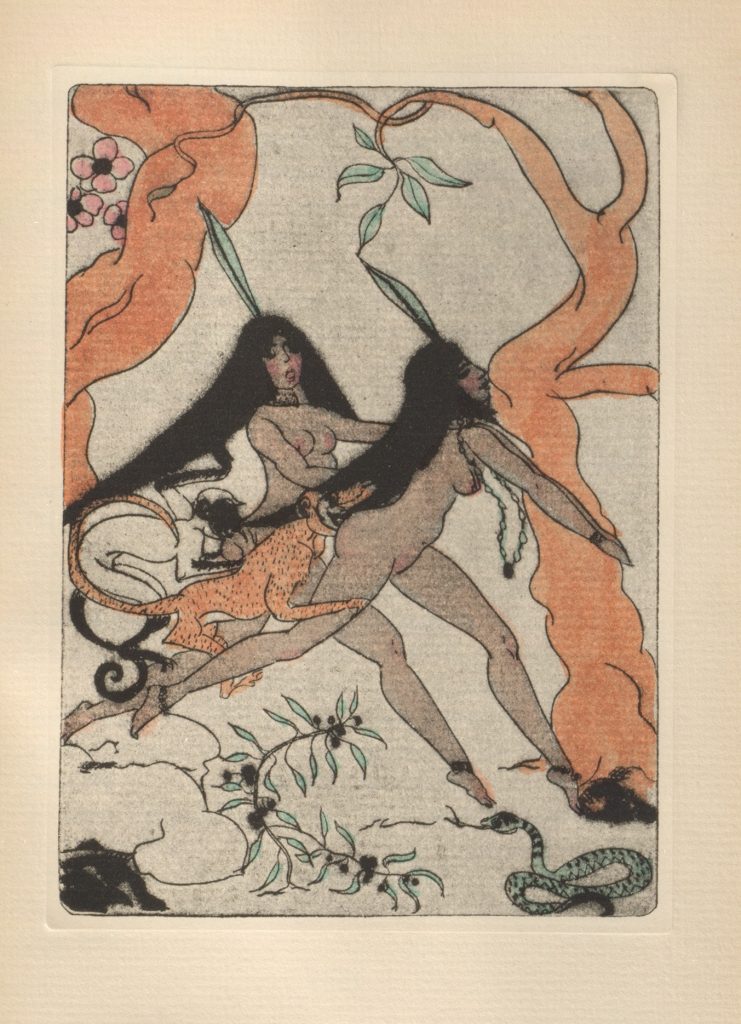

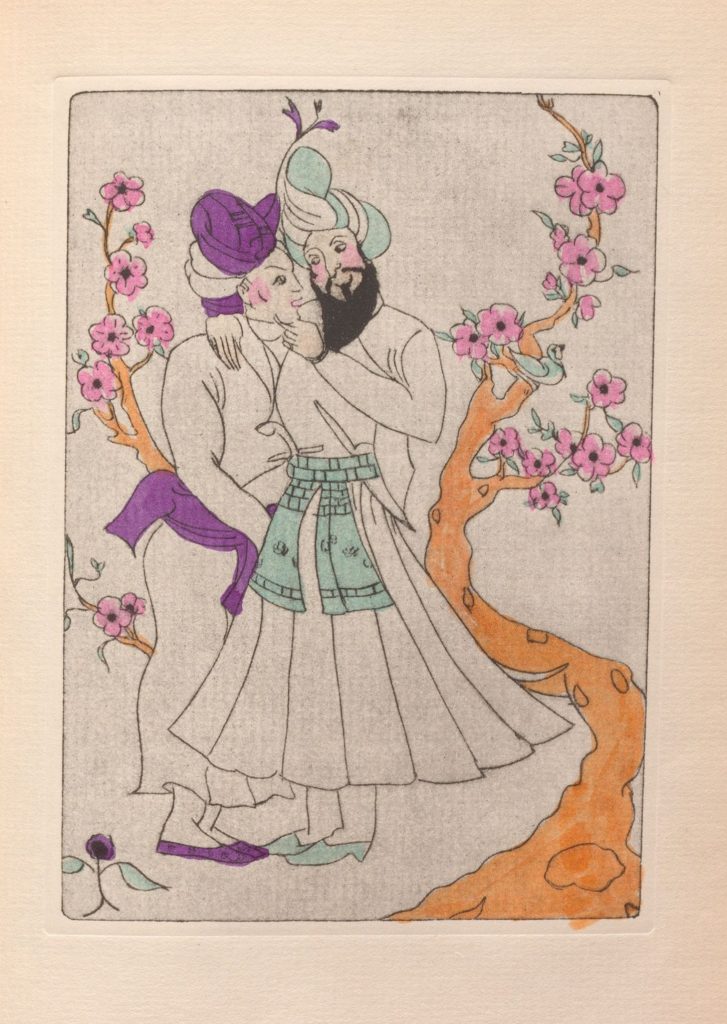

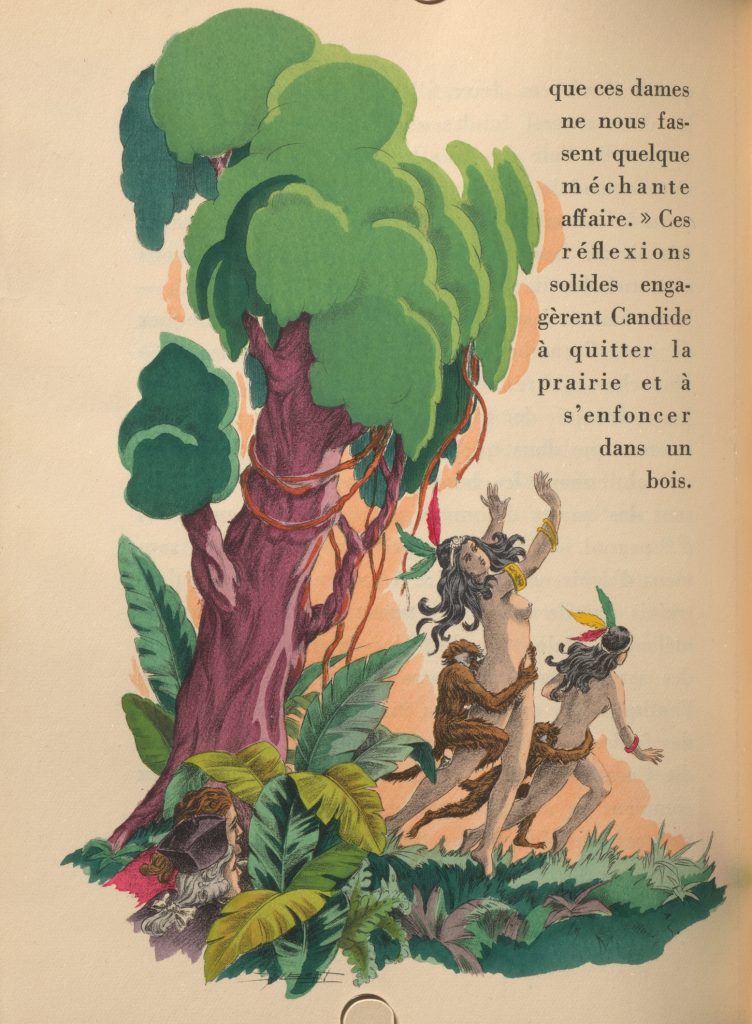

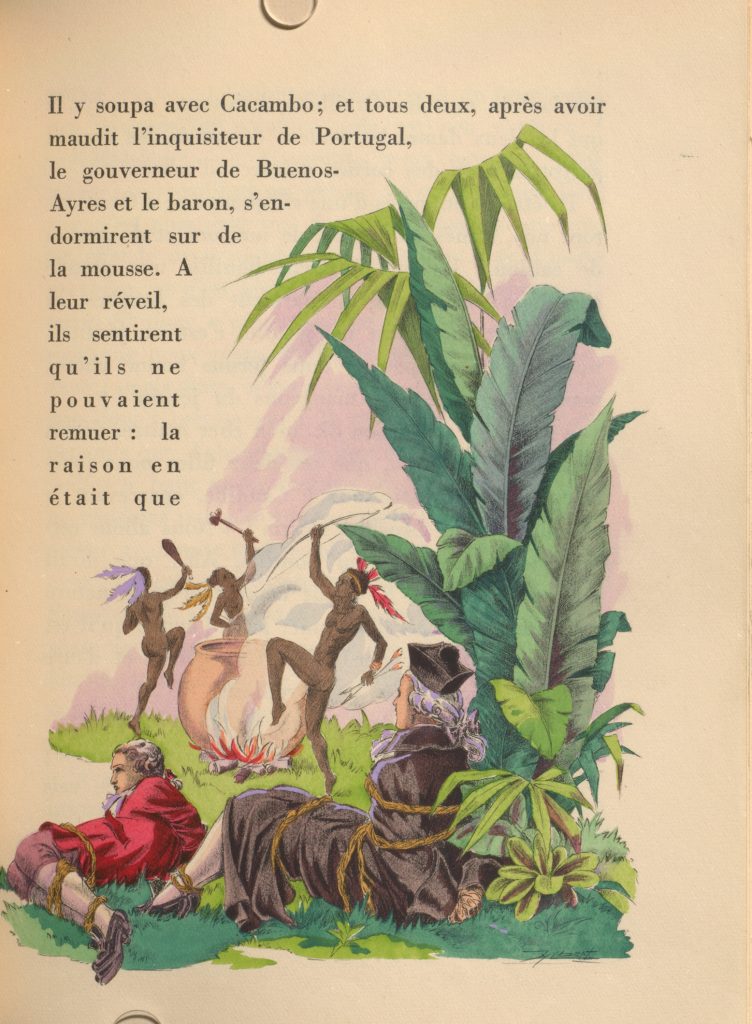

Following the hugely successful publication of Candide in early 1759, there appeared in 1760 a sequel, Candide, seconde partie – an amusing work that we now attributed to the abbé Dulaurens, but that at the time was widely attributed to Voltaire himself, so much so that it was not uncommon for the two parts of Candide to appear together as ‘one’ work by Voltaire. Gradually it became accepted that Voltaire was not the author of the second part, so this practice declined – except in the United States, where the two parts of Candide continued to be published together well into the twentieth century. This is another peculiarity of the American Voltaire – and this fidelity to the apocryphal Second Part of Candide gives illustrators like Clara Tice a wider range of scenes to depict – for example, Candide’s seduction by a lascivious Persian at the start of the Second Part.

Pat Lee’s Voltaire collection contains many of these beautiful objects – another is the illustrated edition by Jylbert, published by the aptly named: Editions du charme. The date here gives us pause for thought, though: the edition appeared in 1941, in occupied Paris. Does the scene with the monkeys in any way reflect what was happening on the streets of the capital?

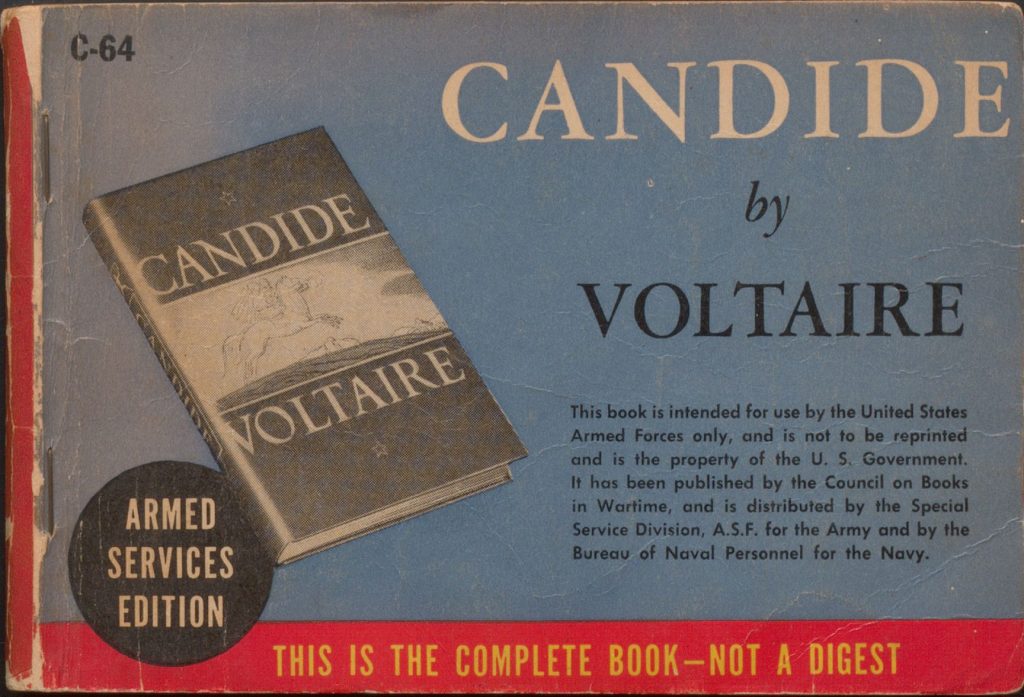

Alongside this precious work, Pat Lee’s collection also includes a humble and modestly printed translation of Candide which appeared in the Armed Services Edition in 1943 – part of a series of books made available to American servicemen and women. In Chapter Three of Candide we remember how both sides in the war have a Te Deum sung, in the certain knowledge that God is on their side… And among the troops who liberated Paris, was there perhaps a serviceman who had Candide in his backpack? The Pat Lee collection gives us a specifically American take on Voltaire and his impact in North America, and as such, it is unique.

Alongside this precious work, Pat Lee’s collection also includes a humble and modestly printed translation of Candide which appeared in the Armed Services Edition in 1943 – part of a series of books made available to American servicemen and women. In Chapter Three of Candide we remember how both sides in the war have a Te Deum sung, in the certain knowledge that God is on their side… And among the troops who liberated Paris, was there perhaps a serviceman who had Candide in his backpack? The Pat Lee collection gives us a specifically American take on Voltaire and his impact in North America, and as such, it is unique.

Click here for more about the Voltaire Foundation

Click here for more about the Voltaire Foundation