This volume of medieval theology offers a rare window into some of the difficulties encountered by scholars in Germany in the years leading up to the Second World War.

As a young scholar at the University of Heidelberg in the early 1930s, historian of philosophy Raymond Klibansky (1905-2005) planned a critical, multi-volume edition of the Latin works of medieval theologian and philosopher Meister Eckhart (d. 1327). Eckhart’s Latin works were less known than his German writings, and because the more scholastic style of these Latin writings involved formal referencing, part of Klibansky’s aim was to underline to a German audience the range of Eckhart’s influences, including Arab and Jewish thinkers. What may look now like an esoteric subject was at the time deeply political, as Eckhart was viewed by Nazi ideologues like Alfred Rosenberg as a father of Aryan thought.

Several obstacles eventually led to the abandonment of Klibansky’s Eckhart edition project after only the first few volumes were published (Vol. 1; Vol. 2; Vol. 13 [=third]). Reasons for the termination of the project included Klibansky’s dismissal as a Jew from Heidelberg University, the seizure of his papers, his move to England, and obstructive measures taken by German authorities against his use of German-held manuscripts. At the same time, a second team was assembled within Germany to produce a complete edition of Eckhart’s works, in this case with the approbation of the government. This edition, the “Stuttgart edition”, produced the now standard critical edition of Eckhart’s works.

The volume shown here, part of McGill’s Raymond Klibansky Collection, is the third volume of the Stuttgart edition, published in 1936. The text is Eckhart’s commentary on the Gospel according to John (Expositio sancti Evangelii secundum Iohannem), a text that Klibansky and his team had begun preparing but had not published before the project was halted.

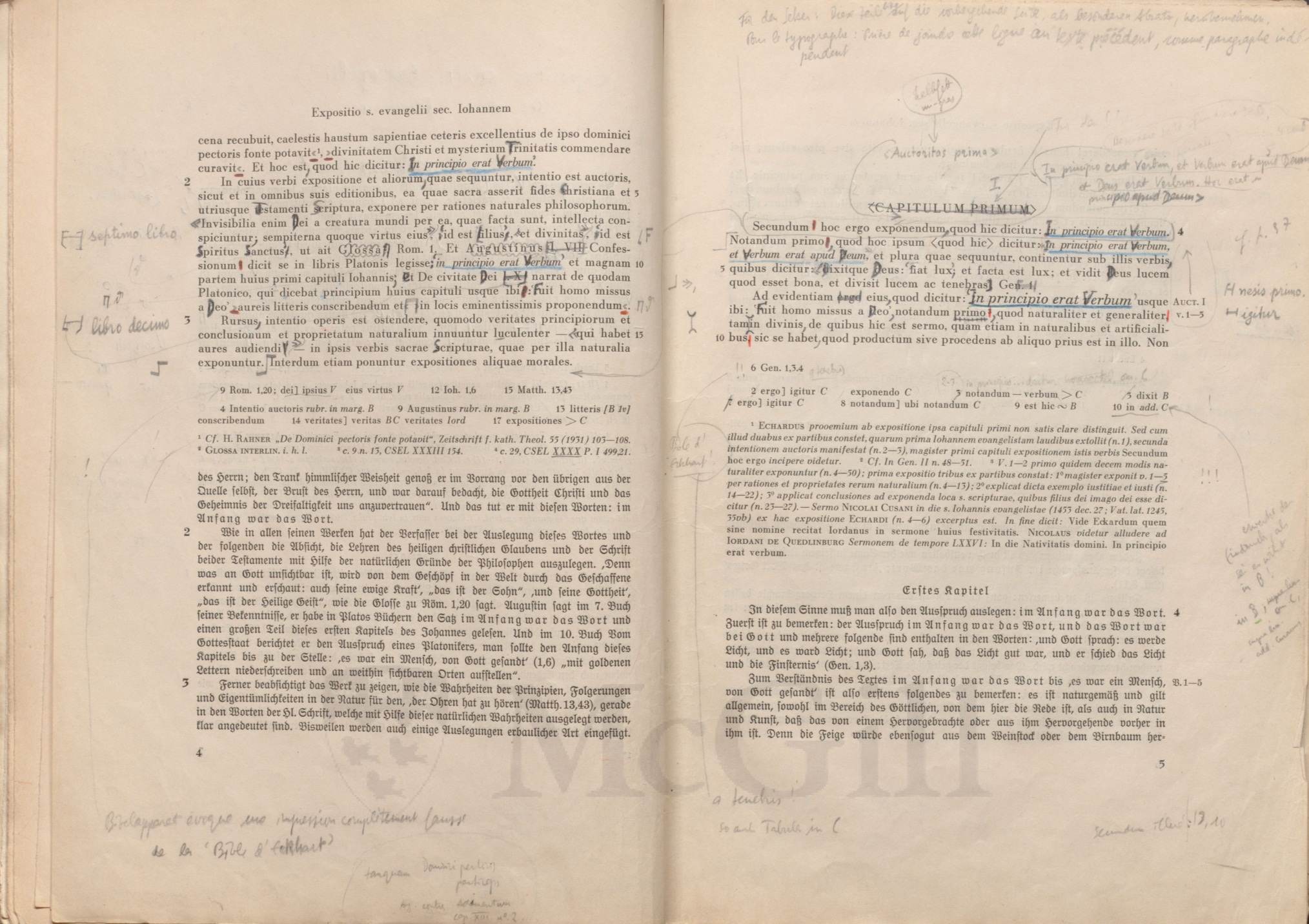

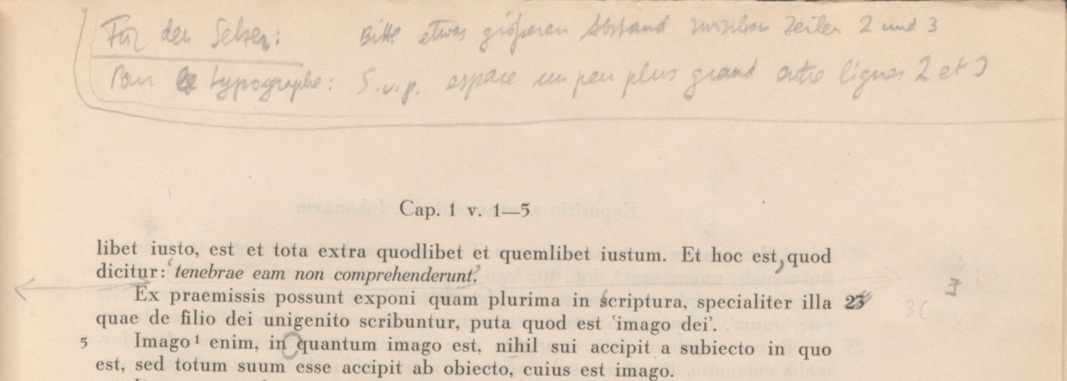

The annotations are in Klibansky’s hand, and are extraordinary both in terms of Klibansky’s own habits and on account of their content. Klibansky did not normally annotate his books heavily. Here, however, nearly every page of the introduction and text, about 80 pages, is marked or annotated in some way. He comments, for example, “Consequentia falsa” (p.xii), “Nonsens!…” (p.3), or “Stupidité de note…” (p. 8). Also, strikingly, there are several handwritten instructions for a typesetter—in both French and German—to reorganize bits of text, as if this were a manuscript in preparation for new publication.

This document offers extraordinary access to an author’s scholarly but also emotional response to a contentious publication. The volume has not yet been the subject of detailed study, and can be consulted in RBSC; this particular text is in volume 3, part 1 (3. Bd., Lief. 1).

Learn more about Klibansky and the Raymond Klibansky Collection.