By Fin Lemaitre*

This month marks the fortieth anniversary of Montreal’s Corridart exhibition—a project that promised to turn Sherbrooke Street into a linear, open-air art museum for just over a month in the summer of 1976. The centerpiece of the cultural programme of the XXI Olympiad, Corridart stretched from Atwater Avenue to Pie IX Boulevard. Organizer Melvin Charney, a Montreal-based artist/architect, envisioned the project as a critical intervention in Montreal’s recent urban development. From a pool of 306 submissions, the competition jury selected for inclusion 22 artists[1] whose proposals addressed collective life and its relation to the built environment.

![Cover of our copy of the limited edition, artist proof copy, of Corridart 1976-. [Montréal : Graff, 1982] 72x52cm.](https://blogs.library.mcgill.ca/rbsc/files/2016/07/Screen-shot-2016-07-02-at-6.10.15-AM.png)

Cover of our copy of the limited edition, artist proof copy, of Corridart 1976-. [Montreal: Graff, 1982] 72x52cm.

Charney, Melvin. Corridart dans la rue Sherbrooke. Montréal : Programme Arts et Culture du Comité organisateur des Jeux olympiques de 1976, [1976]. Pamphlet presenting Corridart on the occasion of the Olympic games, Montreal, in 1976.

Corridart’s participants worked to undermine such assertions. The sculptor Pierre Ayot built a half-scale replica of the monumental Mount Royal Cross (la croix du Mont-Royal sur Sherbrooke),[3] positioning it on its side, as though to lie prostrate before McGill University. Melvin Charney also took up dislocation as a theme. With Les maisons de la Rue Sherbrooke[4] he erected scaffolding-backed plywood replicas of the facades of two limestone heritage buildings. The materials lent the installation the appearance of a work mid-process, but Charney left the process itself ambiguous: the structure fit uneasily into narratives of construction or demolition, progress or decay.

Indeed, it was not only the object of critique that became ambiguous but also the critical apparatus. In Charney’s work, and in Corridart more generally, construction came to double as excavation and art/architecture as archaeology. In these terms we might understand Corridart’s hallmark exhibit, a series of street-side scaffolding installations, called “documentations.” These featured photographs, textual material, and large Mickey Mouse hands, cast in red plastic, pointing towards historically significant objects on the street.

Corridart’s critical politics won it few friends among Montreal’s leaders and power brokers. Mayor Jean Drapeau took personal offence to the exhibition. As if to give grounds for his authoritarian reputation, he ordered a crew of city workers to demolish it. The Mayor’s Office rationalized this course of action by portraying the exhibition as obscene and hazardous to the public. In using this rhetoric, it invoked the same cultural metanarratives of “beautification” and “modernization” that Corridart had critiqued—narratives that obscured the destructive effects of Montreal’s rapid development.

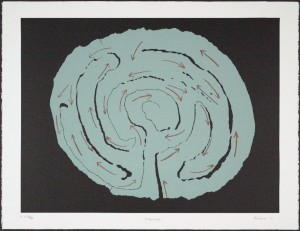

Françoise Sullivan, Labyrinthe. Limited edition print included in “Corridart 1976-“.

Twelve artists filed suit against the city. The lawsuit lasted five years, and failed, due largely to the court’s negative assessment of Corridart’s aesthetic value. In preparation for the cost of an appeal, the artists produced and sold a limited edition of 130 copies, including 21 “artist’s proof” copies in a linen-bound portfolio, Corridart 1976- [Montreal: Graff, 1982]. The tombstone-shaped covers offer a sardonic take on their prospects, but the contents celebrate the achievements of the exhibition. The portfolio contains signed silkscreen prints, excerpts of courtroom testimony, and anti-censorship statements by members of the art community. Our copy of Corridart 1976 (copy IX/XXI) is available for consultation in our reading room during opening hours. Rare Books also holds other materials related to the original exhibition. These include a pamphlet presenting Corridart on the occasion of the Olympic Games, artist submission forms, official invitations to the opening, and a series of posters from a related show, 1972-1976 directions Montréal, mounted at the artist-run gallery Véhicule Art. For those interested in doing further research, the Corridart archive is located at Concordia University.[5]

Update October, 2016: CBC Montreal article, “La croix du mont Royal recreates controversial 1976 exhibit”.

*Fin is a U3 English and history student, and a summer intern at the McGill Visual Arts Collection.

[1] http://archives.concordia.ca/P119

[2] Quoted in Donna Gabeline, Dane Lanken, and Gordon Pape. Montreal at the Crossroads (Montreal: Harvest House, 1975), 9.

[3] https://www.mbam.qc.ca/mirabilia/en/028.html

[4] https://artpublicsphere.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/les-maisons.jpg

[5] http://archives.concordia.ca/P119

Rights

The McGill University Library and Archives respects intellectual property rights as they apply to copyright holders and the public domain. Our use of the material we post is governed by the Canadian Copyright Act and considers both the copyright status of individual works as well as provisions for fair dealing. For any copyright questions or concerns, please contact us.