To supplement the current exhibition in the lobby of Rare Books and Special Collections, “Sir Charles Sebright: The Book-Collecting Baron,” Jason Rovito (Master of Information Studies, Candidate) was invited to write the following text:

Thus counter to that ancient will’s malign,

Who them to the devouring river dooms,

Some names are rescued by the birds benign;

Wasteful Oblivion all the rest consumes.

—Orlando Furioso, Canto XXXV, as translated by W. S. Rose (1858).

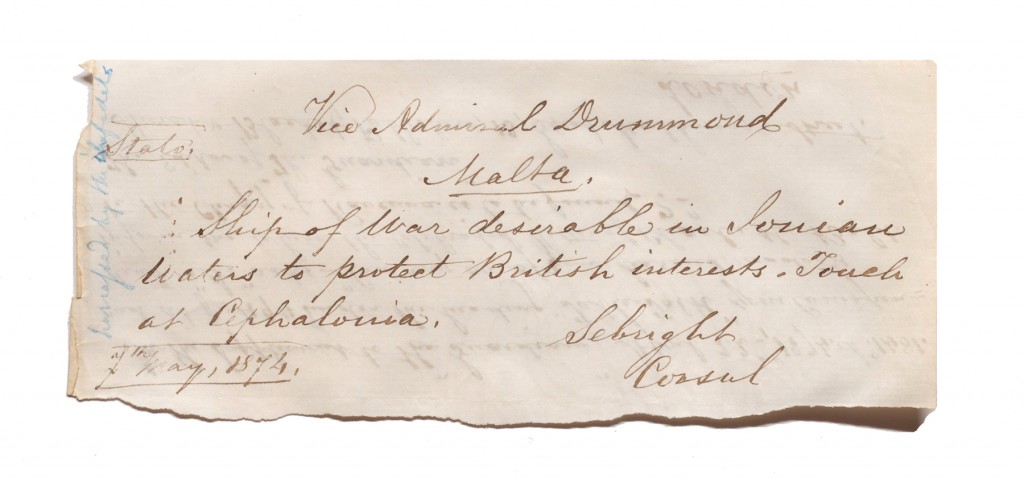

In 1848, on the turbulent Mediterranean island of Cephalonia, insurrection broke out. Amidst a wave of revolutions in Europe, citizens of the United States of the Ionian Islands declared themselves to be Greek. In the middle of this fray was Charles Sebright, the Baron d’Everton, whose book collection is currently being exhibited at McGill’s Rare Books and Special Collections.

Detail from Canto IV, Orlando Furioso (Venice, 1722); from the Sir Charles Sebright Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University.

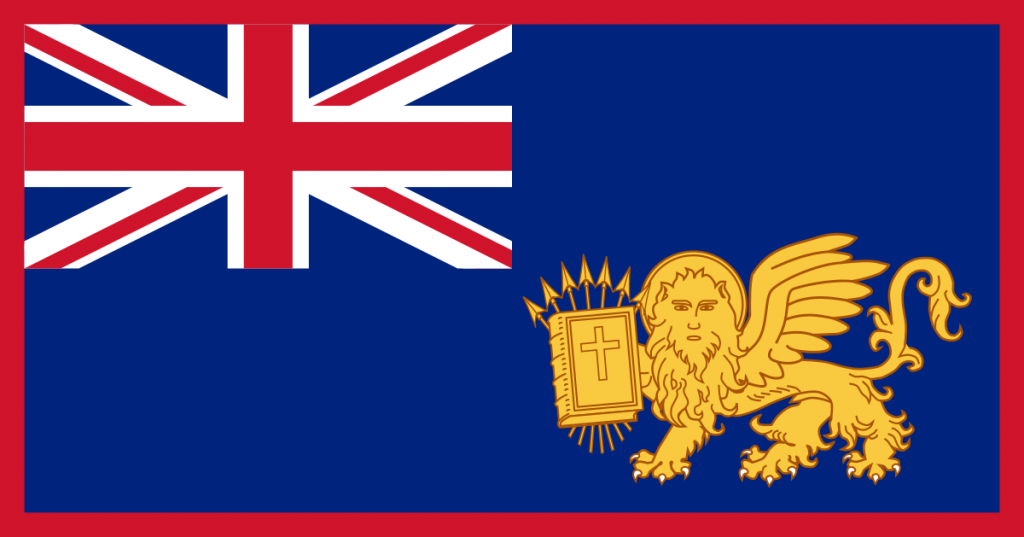

Since 1815, as one of the spoils of the Napoleonic Wars, Great Britain had governed these seven islands as a Protectorate. Prior to Napoleon, they had belonged to the Venetian Republic for almost five centuries. Italian persisted as the language of law, business, and administration, but the British granted the Islanders a constitution, a bicameral legislature, and their own flag. They were also granted British governors, who were called Residents. By the time of the 1848 insurrection, the Scottish-born Charles Sebright had been the Resident of Cephalonia for six years.

“Flag of the United States of the Ionian Islands,” featuring the Venetian icon of the Winged Lion of St. Mark; recreated by ArnoldPlaton (Wikipedia).

With burnt vineyards and wrecked ships, the Lord High Commissioner John Colborne, 1st Baron of Seaton decided to intervene. Having earlier lead the defeat of the Rebellion of Lower Canada, Seaton punished the Islanders with public floggings and executions. For a while, he even suspected Sebright of conspiring with the people. Although these allegations were never proven, Sebright was nonetheless demoted to govern one of the smaller islands. It was here, at Santa Maura, that he would meet his future wife, the pioneering travel writer Georgina Muir Mackenzie, who had been touring the Balkans.

Of Sebright, the most direct account we have is from Viscount Kirkwall (Four years in the Ionian Islands, 1864), who declared: “Alone, perhaps, of all the Residents, he was truly the right man in the right place; both in his public and private capacity he maintained a very high character.” Much of that character survives in his book collection, which was originally donated by his brother to Montreal’s Presbyterian College in 1886. Over two accessions (1987 and 2014) it was transferred, along with an impressive collection of theological books, to McGill’s Rare Books and Special Collections, where it’s now being restored.

Photographs of the gravesite of Sir Charles Sebright and his wife Georgina Muir Mackenzie in Corfu. From the Sir Charles Sebright Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University.

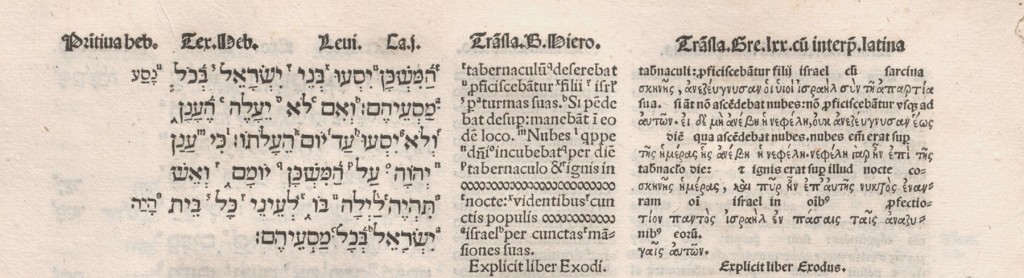

Sebright’s collection likely got its start in the Duchy of Lucca, where he was working as the Duke’s equerry and secretary since at least 1835. “The Duke” was Carlo Ludovico di Borbone Parma, who had previously ruled as the King of Etruria at the age of three. During these last years of the Italian aristocracy, as the Risorgimento bubbled, Carlo Ludovico ruled with a particular style. “The Countess of de Boigne described him as ‘so strangely brought up that he wept if he was obliged to mount a horse, was made ill by the sight of a gun, and when he was obliged one day to cross a ferry was overcome with an attack of nerves.’” And yet: “if as a ruler, he was to prove less able than his brother tyrants, and noticeably less so than the Duke of Modena with whom he was always compared and contrasted, he was certainly more cultured than they. He was an able linguist, a book lover, and something of a student of biblical and liturgical matters, ready to amuse himself with transcription and translation of texts. There are frequent references to his papers, his work in libraries, his progress in Arabic, and similar topics” (Jesse Myers, Baron Ward and the Dukes of Parma).

Detail from the first volume of the scarce Complutensian Polyglot (1514–1517), the first printed polyglot of the entire Bible, initiated by Cardinal Jiménez Cisneros. From the Sir Charles Sebright Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University.

The Duke was a great collector—of both books and paintings—and a long-time correspondent with Antonio Panizzi, who had fled the Duchy of Modena as a suspected Carbonaro to eventually become the controversial Keeper of Printed Books at the British Museum. The Duke also collected debts, which greatly increased after he financed one of the first inter-national railways (from Lucca to Pisa). When money ran short, he auctioned-off his collections. Eventually he would even trade the Duchy of Lucca for solvency, unwilling to rule under a Constitution. Following Italian unification, he would retire from public life as the “Count of Villafranca.”

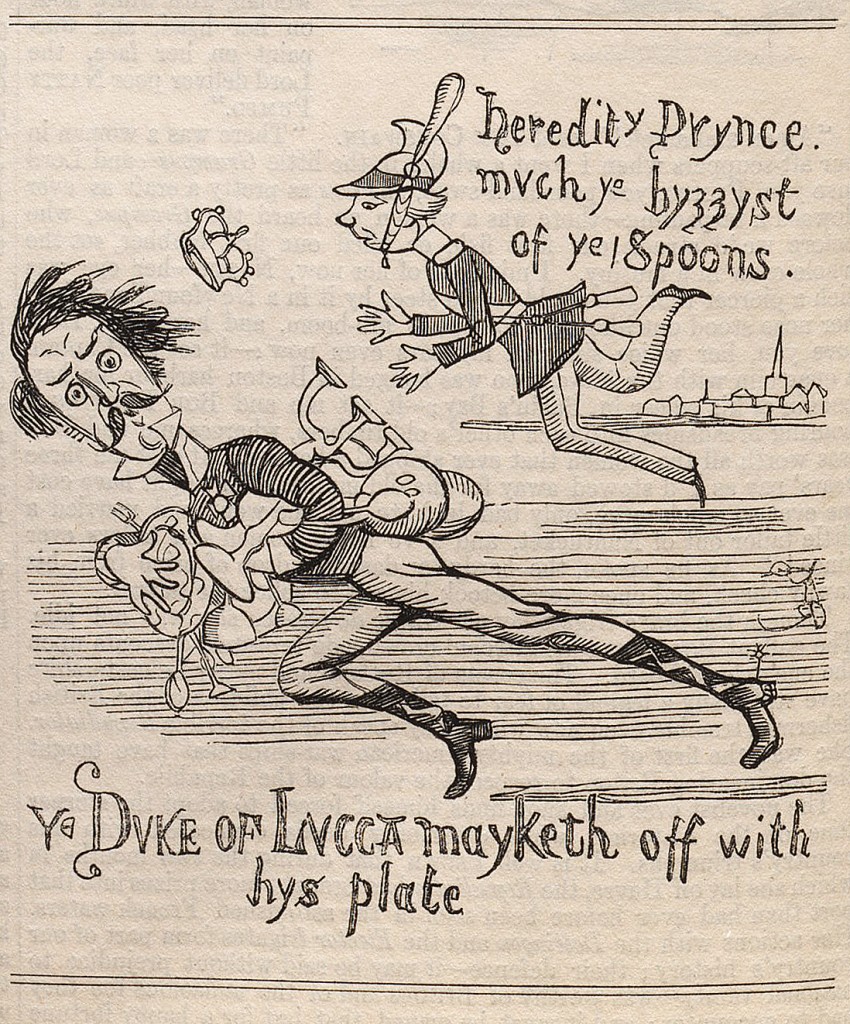

Detail from Issue XIII of Punch, in which the Duke’s 1847 flight from protesters in Lucca was lampooned. From the Serials collection at Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University.

Around 1842, before turmoil in Lucca properly began, the Duke created Sebright as “il Barone d’Everton,” in honour of Sebright’s birthplace near Aberdeen. Sebright was now free to venture south to pursue a career with the British Crown as an Ionian Resident. After twenty two years of service, with the Protectorate finally ceded to Greece, the Baron was knighted as Sir Charles Sebright, KCMG by Queen Victoria and appointed Consul to Cephalonia. By 1870, he was promoted to Consul General for all seven islands and moved, one last time, to Corfu. By all appearances, his book-collecting continued.

The current exhibition showcases a variety of concentrations from Sebright’s collection of nearly 400 books (mostly printed between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries), including incunabula, Italian historiography and literature, and an impressive number of illustrated folios. One of the cases is particularly intriguing, displaying a sample of Sebright’s texts on archaeology, antiquities, and numismatics that seem to conjure his milieu as a mid-nineteenth century collector.

Detail (manipulated) from Le Memorie Bresciane (1693). From the Sir Charles Sebright Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University.

In the 1830s, a newly independent Greece sought to put an end to the exportation of its antiquities. At this time, the Ionian Islands remained a British Protectorate, and thus represented something of a loophole to such export regulations (as did the Aegean Islands that remained under Ottoman control; cf. L. P. Gunning, The British consular service in the Aegean and the collection of antiquities for the British Museum). With increased motivation, British Museum officials openly communicated with their Consular colleagues about undertaking excavations; many of those Consuls had worked as traders with the Levant Company before its absorption by the Crown.

In the middle of such schemes, it’s no surprise to find the name of Antonio Panizzi—the correspondent of Carlo Ludovico di Borbone Parma, whose secretary was once Charles Sebright, the future Consul General of the Ionian Islands. Panizzi was a constant innovator in the pursuit of collection development, which had largely remained an aristocratic pursuit. And yet, while he leveraged the power of the State, Panizzi was a bibliographer, not a bureaucrat. Prefacing his 1834 edition of Orlando Furioso with an introduction of 176 pages, he took great pains to prove that Ariosto’s epic poem was no mere collection of random episodes. Instead, “concealed from the eye by their own luxuriate foliage,” Panizzi names a dizzying series of relations that coil around the chivalrous theme of Love, as counter to the wasteful oblivion of War.

Detail from Francesco Scipione’s Musem Veronese (1749). From the Sir Charles Sebright Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University.

The current exhibition “Sir Charles Sebright: The Book-Collecting Baron” continues until January 2016 in the lobby of Rare Books and Special Collections (4th floor, McLennan Library Building).