This series features Schulich School of Music faculty presenting a selection of books and music that they are exploring – for edification, inspiration, or distraction – during these long months of social isolation. These short interviews seek to emulate the spontaneous interactions that our patrons enjoyed in the Music Library discussing their current reads or the recordings that they had recently discovered (or rediscovered!). Tune in to learn about new works and old favourites, and let us know what you are reading and listening to!

Our first post in this series features Edward Klorman, Associate Professor, Music Theory.

Q: What are you currently reading?

A: Lately, I’ve been reading about how universities operate and trying to understand how students, faculty, and staff can influence a more inclusive culture within large institutions. I recently read a fascinating book called Black Racialization and Resistance at an Elite University by rosalind hampton. The author is a professor of social justice education at the University of Toronto, and the book is based on research she conducted during her doctorate at McGill University, examining what she calls “colonialist ideology” and “a culture of whiteness” endemic to the university. The book is about McGill, but it could be about any number of North American universities, and as a relative newcomer to Québec, it gave me a lot of helpful context. I first encountered the book last summer as part of an anti-racist discussion group in the Music Theory Area, and I reread it when the author recently visited McGill (virtually) for a discussion event sponsored by the Subcommittee on Racialized and Ethnic Persons and the Black Students’ Network.

Next on my reading list is The Fall of the Faculty: The Rise of the All-Administrative University and Why It Matters, by Benjamin Ginsberg, about the shrinking role of faculty self-governance in the affairs of institutions of higher learning, a book that several of my colleagues have recommended.

Q: What are you listening to these days?

A: For almost a year now, I’ve been going on daily walks for at least an hour a day. A lot of my listening lists are podcasts hosted by women and BIPOC hosts, since I enjoy encountering perspectives beyond my own experience. Lately, I’ve been listening to podcasts focusing on history (or alternative versions of familiar history) that go beyond what I learned in school. One of my favorites is NPR’s Throughline.

One podcast I’ve listened to lately is called “The Test Kitchen” from Reply All. It focuses on issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion at the magazine Bon Appetit over the past decade and why the workplace culture promoted white writers, editors, and chefs, while keeping others in subordinate positions. It’s very well reported, offering perspectives from many employees who worked at the magazine, and it may offer some insights into work cultures and barriers to cultural change at some musical and academic institutions. One complication around this podcast, though: some of the producers who developed it have themselves been accused by co-workers of undermining diversity and equity efforts at their own company. I still recommend the podcast series, but a lesson learned for me is that it’s always important to listen to and amplify the most marginalized voices in discussions around diversifying our workplaces and institutions.

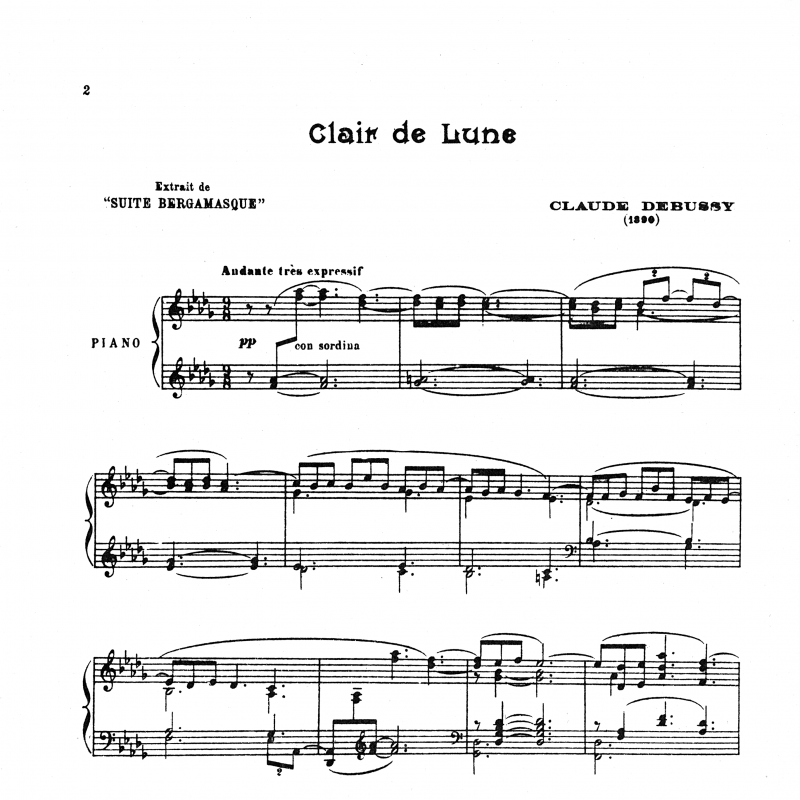

I’ve also been listening a lot to Bach’s cello suites, since I’m currently at work on a book on those pieces and am keen to hear different performance approaches. And I’ve also been listening to musicians who’ve passed away during the pandemic. This week, I’ve been listening to the folk singer and activist Anne Feeney, who is probably best known for “Have You Been to Jail for Justice?” and “Union Maid,” and who sadly succumbed to COVID earlier this month.

Q: Have you been able to attend any virtual concerts or conferences? If so, can you tell us about one?

A: It’s been fascinating to see the creative ways my musician and scholar friends have stayed active in new ways during this period of physical distancing! One highlight this year was Diversifying Music Academia 2020, sponsored by Project Spectrum, a graduate student-led coalition with a mission of bolstering community and shifting the culture within our disciplines toward confronting racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination. A few things really struck me about this (virtual) symposium: the grassroots organizing and coalition building led by graduate students, the engagement across subdisciplines (such as historical musicology, ethnomusicology, and theory), and the focus on identifying forms of exclusion or injustice that can often be hard to recognize.

Q: What are you most looking forward to post-Covid?

A: Like everyone else, I’m looking forward to visiting with friends and family and to attending live music, theater, and dance. I’m keenly aware of how challenging this extended period of physical distancing and remote interaction has been for so many students, in terms of straining our social connections, challenges to physical and mental wellbeing, financial precarity, and so on. So I’m looking forward to a time when these concerns will be less acute and we can focus more on learning, making music, and building our community together.