An Exhibition curated jointly curated by the Islamic Studies Library and the Osler Library of the History of Medicine running from September 11th to December 22nd, 2023.

The practice of medicine in the region sometimes referred to as the Islamic World[1] predates the revelation of Islam: therapeutic practices before Islam relied heavily on Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Persian, Indian, and Greek medical knowledge. During the early and medieval periods of the Islamic era, physicians in the region achieved advancements and innovations that have had a lasting and significant impact on the evolution of medical practices around the world. This exhibition aims to show how medical knowledge first came to the Islamic World (pre-Islam until the 10th cent. AD/4th cent. AH), then circulated and developed within the region (between the 11th and 16th cent. AD/5th-10th cent. AH), before being exported to Europe (during the 17th and 18th centuries. AD/11th-12th cent. AH).[2] Visitors will learn how the translations of foreign medical texts (from Greek, Sanskrit, Syriac, etc.) into Arabic and Persian eventually led to the need to codify such a large body of knowledge for the purpose of dissemination. Visitors will also gain an appreciation for the wealth and depth of knowledge produced by physicians who practiced in Islamic lands, especially in fields like ophthalmology, pharmacology and surgery. Finally, visitors will understand the lasting and significant impact that medical knowledge produced in the Islamic World has had on modern Western medicine. Through the display of original manuscripts, books, and antique artefacts from the Islamic Studies Library (ISL), and the Osler Library of the History of Medicine, The rise and influence of Medicine in the Islamic World will take visitors on a fascinating journey into the world of Islamic medicine.[3]

Comprising two complementary displays -one at the Islamic Studies Library and other at the Osler Library-, the exhibition will be accessible during libraries opening hours from September 11th to December 22nd, 2023.

[1] For geographical location, contemporary denominations of countries have been used even if the national entities known today did not exist in their current frontiers at the time. The geography of the region was in constant flux during the long period covered by the exhibition and referring to today’s place-names appeared like the easiest way to situate individuals and events.

[2] For dating, both the Gregorian calendar (AD) and the Hijri calendar (AH) have been used most of the times. An exception was made for Greek and European physicians for whom only Gregorian dates are given.

[3]The rise and influence of Medicine in the Islamic World was jointly curated by Anaïs Salamon and Ghazaleh Ghanavizchian from the ISL, and Dr. Mary Hague-Yearl from the Osler Library.

Pre- & early Islamic Medicine

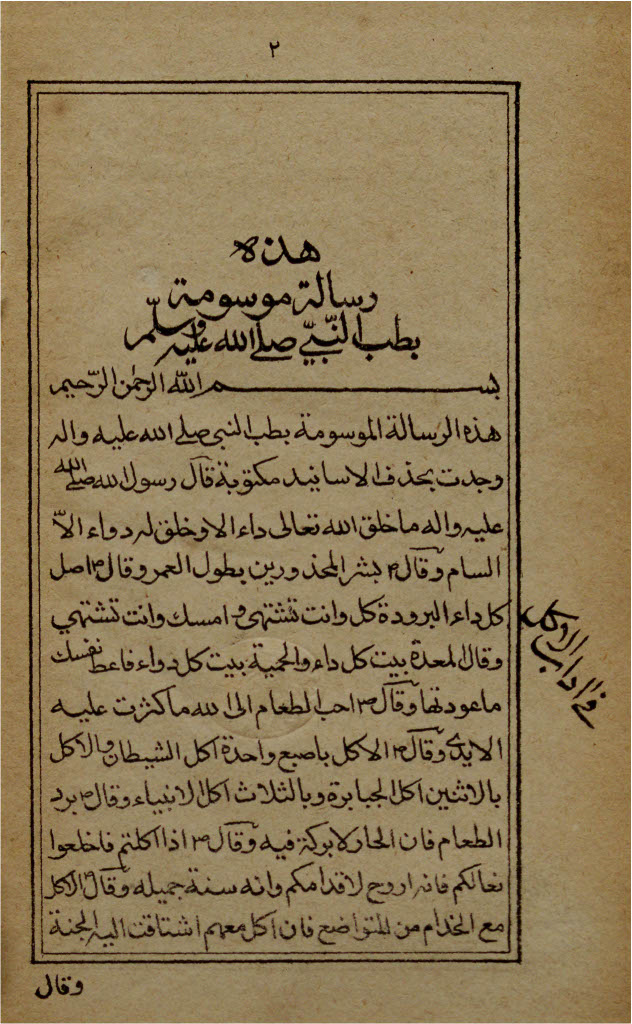

Medical practices before Islam came from Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Persian, Indian, and Greek physicians. After the rise of Islam (7th cent. AD/1st cent. AH), pre-Islamic medicine remained in use until the beginning of the Umayyad Caliphate (660-750 AD/40-132 AH). From the 9th cent. AD/3rd cent. AH onwards, a new type of medicine emerged by adopting Greco-Islamic medical knowledge and recorded as Ḥadīth [Reports from the Prophet Muḥammad]: This Prophetic medicine drawn from Ḥadīth co-existed with other types of medical care – like Greek humoral medicine – and kept developing until the 14th cent. AD/9th cent. AH.

The Translation of Foreign Texts

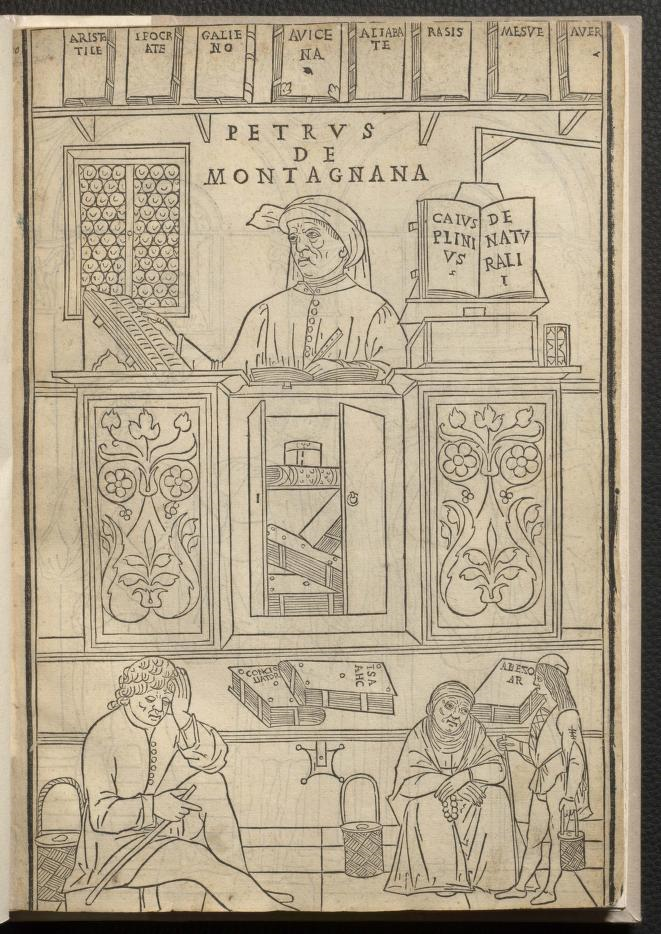

During the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258 AD/132-651 AH), significant effort went toward translating medical and scientific works from other cultures and languages. Established in the 9th cent. AD/3rd cent. AH in Baghdad (Iraq), Bayt al-Ḥikmah / بيت الحكمة [The house of wisdom] supported the translation of foreign texts into Arabic. Many Arab physicians started as translators before composing their own works. Two examples are the Arab Nestorian Christian Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq,[4] the author of a fundamental ophthalmological treatise, and the Syriac Christian Ibn Māsawayh,[5] the author of many works on fevers, leprosy, melancholy, and other topics. The most commonly translated texts at the time were the Compendium on materia medica by Dioscorides[6] as well as the works of Hippocrates[7] and Galen[8] in humoral medicine.

By the end of the 9th cent. AD/3rd cent. AH, Hellenistic humoral medicine – based on the balance between four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile – had become prominent in the region. However, prophetic medicine was still very popular, and physicians often blended the two approaches together when curing patients until the 14th cent. AD/9th cent. AH.

In the late 9th – early 10th cent. AD/3rd – 4th cent. AH, the first hospitals appeared in Iraq and Egypt and then started spreading throughout the Islamic World. For sovereigns, such institutions were part of charitable endeavors and cam to symbolize political power. For physicians, hospitals were a place where they not only cured patients, but also taught and trained aspiring physicians.

[4] Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq al-ʿIbādī. حنين بن إسحاق العبادي (Iraq, 808–873 AD/192-259 AH) was the most famous translator of Greek texts into Syriac and Arabic. His translations formed a foundation for the continuation of Galenic medicine amongst Muslim physicians and, through their mediation, in the mediaeval West.

[5] Ibn Māsawayh. ابن ماسويه (Iraq, died 857 AD/243 AH) began his career translating Greek scientific works for the famous Bayt al-ḥikmah, but became a court physician, attending the high society around the caliph.

[6] Dioscorides (Greece, active in the first century C.E.) is Pedanius Dioscorides of Anazarbos, Greek physician and herbalist, and author of De materia medica that formed the basis of the pharmacological tradition of the classical Islamic world.

[7] Hippocrates (Greece, born after 460, died circa 379 B.C.E.) is considered in both the Muslim world and the West as “the father of medicine.” The Corpus Hippocraticum -writings attributed to him- comprises about seventy titles. However, the authorship of many of them has been a matter of dispute since antiquity. Hippocrates nevertheless drew the first outlines of humoral medicine.

[8] Galen (Turkey, 129-circa 216 C.E.) was a Greek-speaking physician born in Pergamum. His vast work (more than 20,000 pages in a standard 1821 edition) deals with all fields of medical science (anatomy, physiology, therapy, pharmacology, surgery), but also extends to philosophy, logic, ethics, etc.

The Organization & Dissemination of Knowledge

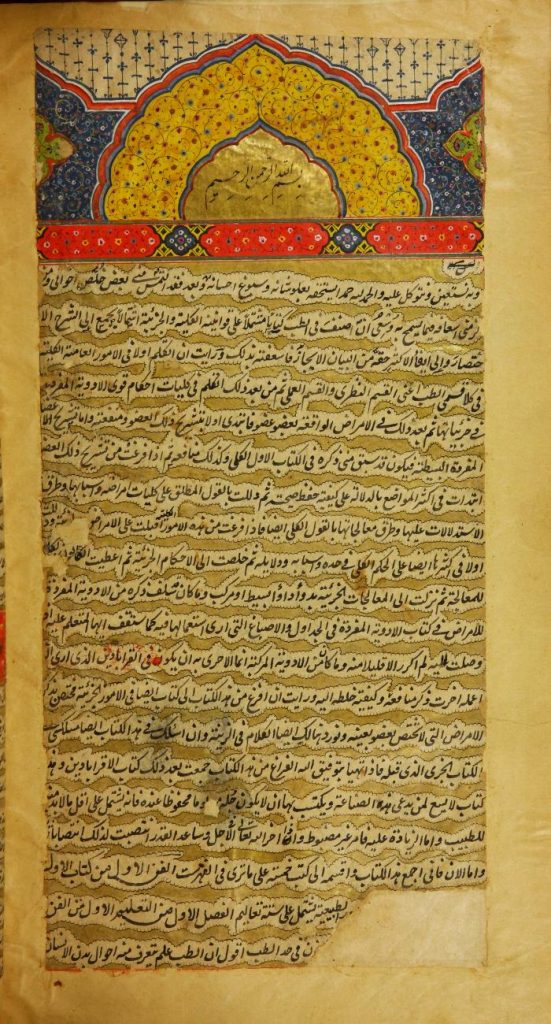

In the 10th and 11th cent. AD/4th – 5th cent. AH, compiling and organizing what had become a large body of knowledge became the priority. Thus, comprehensive influential encyclopaedias were composed: examples include/ كتاب المنصوري في الطب Kitāb al-Manṣurī fī al-ṭibb [The book on medicine dedicated to al-Mansur] and كتاب الحاوي في الطب / Kitāb al-Ḥāwī fī al-ṭibb [The Comprehensive Book on Medicine] both by Abū Bakr al-Rāzī,[9] and/ كتاب القانون في الطب Kitāb al-Qānun fī al-ṭibb [The canon of medicine] by Avicenna.[10] If such encyclopaedic works were not always well received by the medical community at the time of composition, they served as the foundation of later important works like those of Averroes,[11] Ibn al-Nafīs,[12] and many others.

[9] Abū Bakr al-Rāzī -or Rhazes-. أبو بكر محمد بن زكريا الرازي(Iran, 854-925 or 935 AD/240-313 or 323 AH), known to the Latins as Rhazes, was a physician, philosopher and alchemist. His medical handbook (Mansuri) and other writings were translated over a dozen times into Latin and other European languages.

[10]Ibn Sīnā -or Avicenna-.أبو علي حسين بن عبد الله بن سينا (Iran, 980-1037 AD/370-428 AH) was known primarily as a philosopher and physician, but he contributed to the advancement of many more sciences accessible in his day: astronomy, music, politics, religion, poetry, etc. Divided in five books (1. Generalities, 2. Pharmacology, 3. Special pathology, 4. Treatises, 5. Pharmacopeia), his Qanun is the clear and ordered sum of all the medical knowledge available at the time, augmented from his own observations. The Qanun served as a reference for seven centuries of medical teaching and practice.

[11] Ibn Rushd -or Averroes-. محمد إبن احمد إبن رشد(Spain, 1126-1198 AD/520-594 AH) was known primarily as a philosopher and theologian, but also specialized in the natural sciences (physics, medicine, biology, astronomy). He wrote several treatises about stroke, a neurological disease similar to Parkinson, and the anatomy of the eye. The encyclopaedia co-authored with Avenzoar – or Ibn Zuhr – (Spain, died 1162) entitled Al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb was translated into Latin in the 14th century A.D. and became a textbook in Europe for centuries (known as the Colliget).

[12] Ibn al-Nafīs. ابن النفيس (Syria, 1210-1288 AD/607-687 AH) is the author of one of the most widely read commentaries on Avicenna’s Qānūn fī l-ṭibb in the pre-modern Islamic world. He was also the first physician to propose that blood travels from the right side of the heart to the left through the lungs (pulmonary transit).

The Emergence of Specialties

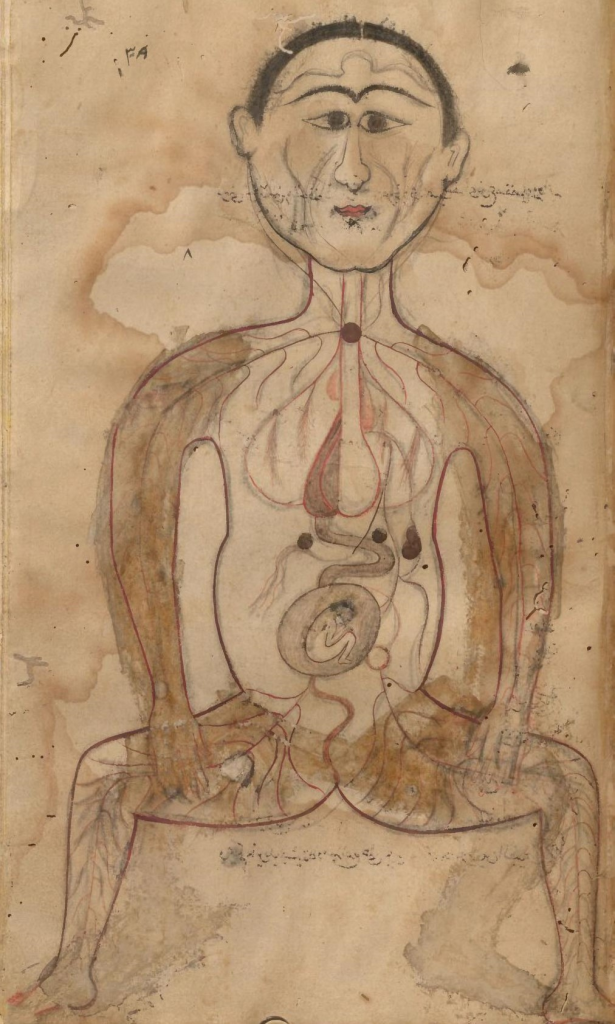

Ophthalmology, pharmacology and surgery quickly emerged as medical specialties in the Islamic World as demonstrated by the number of dedicated monographs. Other topics such as anatomy, bloodletting or embryology were also sometimes the subject of monographs, but these did not become as influential as encyclopaedias chapters on the same topics.

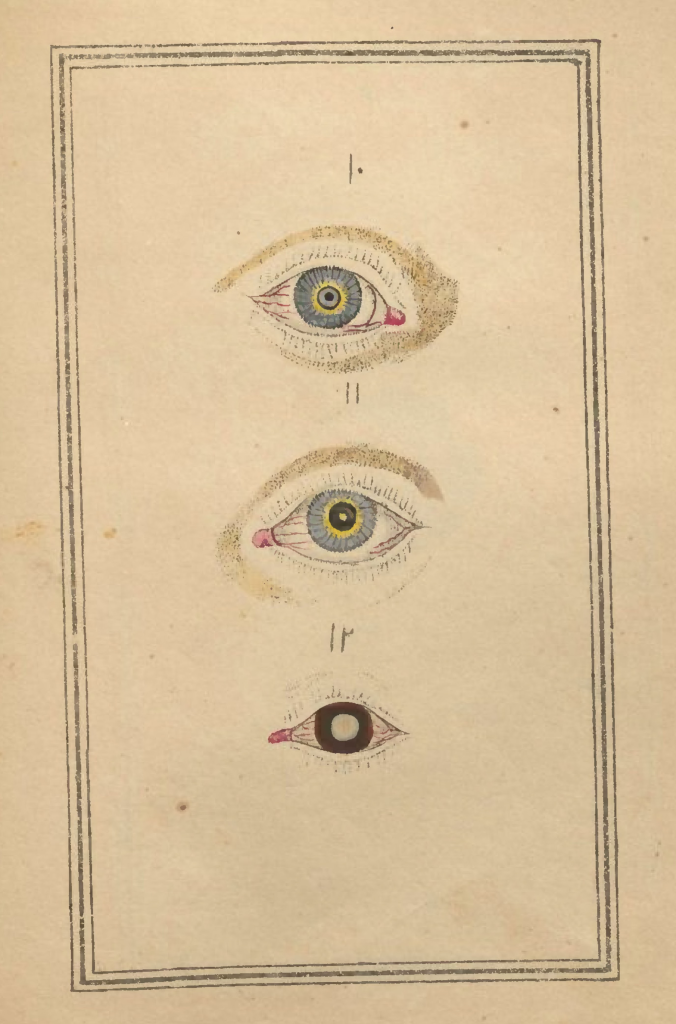

Ophthalmology

Ophthalmological works composed as early as in the 9th cent. AD/3rd cent. AH already show very advanced knowledge: grounded in theories inherited from the Hellenic World, they included intricate surgical procedures to treat common eye diseases like cataracts. One of the most renowned works from the early period is تذكرة الكحالين /Tadhkirat al-Kaḥḥālīn [Memorandum of the oculists] by ʿAlī ibn ʿĪsá[13] (11th cent. AD/5th cent. AH). A few centuries later, in the 14th cent. AD/9th cent. AH, Ibn al-Nafīs compiled in a systematic way the ophthalmological knowledge of the time in/ كتاب المهذب في طب العين Kitāb al-Muhadhdhab fī ṭibb al-ʿayn [Ophthalmology manual].

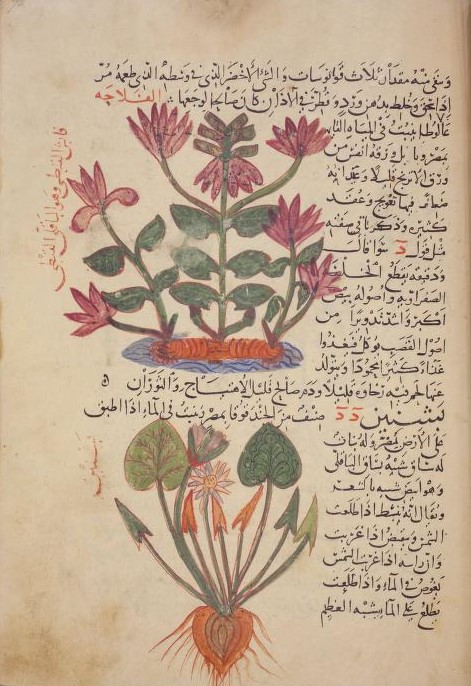

Pharmacology

Physicians in the Islamic Era commonly used the 500 substances described in Dioscorides’ Compendium in addition to drugs used in Indian and Persian medicine. The 10th cent. AD/4th cent. AH writings of Qustā ibn Lūqā[14] included drugs such as camphor or ammoniac that were unknown at the time to Greek and European physicians. In the 12th cent. AD/6th cent. AH, al-Ghafīqī[15] compiled a list of medicinal substances ordered alphabetically entitled كتاب الأدوية المفردة / Kitāb al-adwiyāʾ al-mufradah [The book of simple drugs].

This work served as a basis for a later manual authored by Ibn al-Baytar[16] (13th cent. AD/7th cent. AH) that presented a total of 1,400 medicaments and became a reference for many subsequent guides in the Islamic World and beyond.

Surgery

Many physicians in the medieval Islamic medical tradition were interested in surgery. One of the most famous surgeons was al-Zahrāwī[17] (11th cent. AD/5th cent. AH) whose thirty-volume encyclopaedia entitled/ كتاب التصريف لمن عجز عن التأليف Kitāb al-Taṣrīf li-man ʿajiza ʿan al-taʾlīf [The arrangement of medical knowledge for one who is not able to compile a book himself] was quoted over 200 times by 14th cent. AD/9th cent. AH French surgeon Guy de Chauliac.[18]

Another important contributor to surgical knowledge was Abū al-Faraj ibn al-Quff[19] (13th cent. AD/7th cent. AH) who composed a substantial monograph on surgery, كتاب العمدة في صناعة الجراحة / Kitāb al-ʿUmdah fī ṣināʿat al-jirāḥah [The mainstay in the art of surgery], which comprised twenty chapters covering anatomy, physiology, general surgical principles, and a pharmacopoeia (recipes for compound drugs used in surgery).

[13] ʿAlī ibn ʿIsá al-Kaḥḥāl. علي بن عيسى الكحال (Iraq, died 1038 or 1039 AD/429 or 430 AH) was the best known oculist (kaḥḥāl) of the Arabs. His work, the Tad̲h̲kirat al-Kaḥḥālīn , is the oldest Arabic work on ophthalmology that survived in the original. This comprehensive treatise was translated into Hebrew and Latin in the 15th century A.D.

[14] Qustā ibn Lūqā. قسطا ابن لوقا (Syria, died 912 or 913 AD/299 or 300 AH) worked as a physician and translator -he was fluent in Greek, Syriac and Arabic-. His medical works include treatises on gout, infectious diseases, insomnia, fevers, types of crises in illnesses, the pulse, paralysis-types, causes and treatment, the four “humours”, and phlebotomy.

[15] Al-Ghāfiqi. أبو جعفر أحمد بن محمد الغافقي (Spain, 12th cent. AD/6th cent. AH) was regarded as the best expert on drugs of his time.

[16] Ibn al-Bayṭār. ابن البيطار (Spain, died 1248 AD/646 AH) was a botanist and pharmacologist. Some historians consider he plagiarized al-Ghafiqi’s Kitāb fī l-adwiya al-mufrada to compose his al-Jāmiʿ li-mufradāt al-adwiya wa-al-ag̲h̲d̲h̲iya.

[17] Abū al-Qāsim al-Zahrāwī -or Abulcassis-. أبو القاسم الزهراوي (Spain, 936-1013 AD/ 324-404 AH) was an innovative physician, surgeon and chemist whose influence continued for centuries and extended far beyond the frontiers of the Muslim Worlds.

[18] Guy de Chauliac (France, 1300-1368 AD) was a physician and surgeon famous for his treatise Chirurgia Magna that was translated in numerous languages and served as a reference until the 16th century.

[19] Abū al-Faraj ibn al-Quff. أبو الفرج بن يعقوب بن إسحاق ابن القف (Jordan, 1233-1286 AD/630-685 AH) was a Christian physician and surgeon better known as a writer and educator than as a doctor.

Knowledge Exchanges

The medical community in the Islamic World remained quite productive through the 14th cent. AD/9th cent. AH, especially in Syria and Egypt. In the latter half of the 16th cent. AD/10th cent. AH, early modern European medical ideas, techniques, and drug therapies started filtering into the Islamic World. Dāʾūd al-Antakī[20] included 1,712 mineral, animal and plant substances from Egypt, Europe, India, China, the Levant, North Africa, and Asia Minor. In hisتذكرة أولي الألباب والجامع للعجب العجاب / Tadhkirat ulī al-albāb wa al-jāmiʿ li al-ʿajab al-ʿujāb [Memorandum book for those who have understanding and collection of wondrous marvels] (1568 AD/975 AH), followed the European practice of using China Root (Chub-chini) to cure syphilis. In a treatise dedicated to syphilis written in 1569 AD/ 977 AH, ʿImād al-Dīn Masʿūd Shīrāzī[21] also prescribed China Root as a cure.

In the 17th cent. AD/11th cent. AH, Ibn Sallūm’s[22] treatise entitled غاية الاتقان في تبدير بدان الانسان / Ghāyat al-itqān fī tadbīr badān al-insān [The culmination of perfection in the treatment of the human body] originally composed in Arabic and later translated into Ottoman Turkish, included translations of several Latin writings by Paracelsus.[23] But knowledge also circulated in the other direction: Europeans became interested in learning of the medical practices then current in the Islamic World. In 1681 AD/1092 AH, Joseph Labrosse[24] published Pharmacopoea Persica ex idiomate Persica in Latinum conversa which consisted of the Latin translation of a Persian book on compound remedies with personal notes and comments.

[20] Daʾūd al-Antakī. داؤود الأنطاكي (Egypt, 16th cent. AD/10th cent. AH) was a blind physician and pharmacist who authored a three-part medical encyclopedia that included descriptions of over 3,000 medicinal and aromatic plants.

[21] ʿImād al-Dīn Masʿūd Shīrāzī. عماد الدین مسعود شیرازی (Iran, mid-16th cent. AD/ mid. 10th cent. AH) was a physician who composed a number of treatises in Persian and Arabic on the therapeutic values of Opium and China root (species of smilax). European influence is visible in his works.

[22] Ṣāliḥ b. Naṣrullāh Ibn Sallūm al-Ḥalabī. صالح بن نصر الله بن سلوم الحلبي (Syria, died 1670 AD/1081 AH) was the head physician of the Ottoman Empire whose writings are often seen as instrumental in the introduction of European Renaissance medicine to the Middle East.

[23] Paracelsus (Switzerland, 1493-1541 AD) was a physician, alchemist, theologian, and philosopher. He is one of the first scientists to introduce chemistry to medicine advocating for the use of inorganic salts, minerals, and metals for medicinal purposes. Instead of the four humour of Hellenistic medicine, he believed there were three humours: salt, sulphur, and mercury respectively representing stability, combustibility, and liquidity.

[24] Joseph Labrosse (France, 1636-1697 AD), also known as Father Angelus of St. Joseph, was a French Carmelite missionary and writer. He played a role in transmitting Persian medical terminology to Europe, and was the first European to make a serious study of Iranian medicine. He also compiled a Persian dictionary with translations into Latin, French, and Italian.

The Rise of European Medicine as the Reference

In the middle of the 18th cent. AD/12th cent. AH, traditional Islamic medicine seemed unable to combat the plague epidemic in Istanbul. The Ottoman sultan Mustafa III ordered a Turkish translation of two treatises by Hermann Boerhaave.[25] These translations, soughing to reconcile and harmonize Boerhaave’s ideas with traditional Islamic medicine, were completed in 1768 AD/1182 AH.

The 19th cent. AD/13th cent. AH witnessed profound changes in the teaching of medicine in the Islamic World as European medical expertise became the reference point. In 1825 AD/ 1240 AH, the Egyptian army hired French physician Antoine-Barthélémy Clot[26] as surgeon-in-chief. A few years later, Clot established a medical school near Cairo which French, Italian and German professors. Similarly, a military medical school, دار الفنون / Dār al-Funūn [The house of arts] founded in Tehran (Iran) in 1850 AD/ 1266 AH offered instruction in French based on European medical texts translated into Persian.

Nevertheless, aspects of medieval Islamic traditional medicine continued to coexist alongside modern European medicine. In the late 19th cent. AD/13th cent. AH, treatises of Ibn Sīnā and Ibn al-Bayṭār, among others, were still printed at the بلاق / Būlaq Press ( / المطبعة الأميريةal-maṭbaʿah al-amīrīyah) in Cairo because they continued to represent a vital tradition.

[25] Hermann Boerhaave (Netherlands, 1668-1738 AD) was a Dutch botanist, chemist and physician considered to be the founder of clinical teaching and of the modern academic hospital, and sometimes referred to as “the father of physiology”. He is best known for demonstrating the relation of symptoms to lesions.

[26] Antoine-Barthelemy Clot (France, 1793-1868 AD) also known as Clot Bey is a French physician and medicine professor who spent most of his life working in Egypt.

Bibliography

Abel-Halim, R. E. (2018). Surgery. In Pormann, P. E. (Ed.), 1001 Cures: Contributions in Medicine & Healthcare from Muslim Civilisation. London: Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation. https://www.1001cures.net

Arnaldez, R. (2012). “Ibn Rus̲h̲d”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0340

Bowen, H. (2012). “ʿAlī b. ʿĪsā”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_0512

Brockelmann, C. and Vernet, J. (2012). “al-Anṭākī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_0681

Carra de Vaux, B. (2012). “Ṭibb”, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, First Edition (1913-1936), edited by M. Th. Houtsma, T.W. Arnold, R. Basset, et. al. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2214-871X_ei1_SIM_5758

Goichon, A.M. (2012). “Ibn Sīnā”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0342

Goodman, L.E. (2012). “al-Rāzī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_6267

Grenon, P. (2018). Compete or complete: a contextualist approach on prophetic medicine (dissertation). McGill University Libraries. https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/j6731645v

Hamarneh, S. K. (2012). “Ibn al-Ḳuff”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_8659

Hill, D.R. (2012). “Ḳuṣtā b. Lūḳā”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_4567

Meyerhof, M. and Schacht, J. (2012). “Ibn al-Nafīs”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_3319

Savage-Smith, E. (2013). “al-Ghāfiqī, Muḥammad”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, edited by K. Fleet, G. Krämer, D. Matringe, et. al. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_27421

Savage-Smith, E. (2012). “al-Zahrāwī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_8089

Savage-Smith, E., Klein-Franke, F. and Zhu, Ming. (2012) “Ṭibb”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1216

Shahpesandy, H., Al-Kubaisy, T., Mohammed-Ali, R., Oladosu, A., Middleton, R., and Saleh, N. (2022) A Concise History of Islamic Medicine: An Introduction to the Origins of Medicine in Islamic Civilization, Its Impact on the Evolution of Global Medicine, and Its Place in the Medical World Today. International Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13, 180-197. https://doi.org.10.4236/ijcm.2022.134015

Shefer, M. (2011). An Ottoman Physician and His Social and Intellectual Milieu: The Case of Salih bin Nasrallah Ibn Sallum1, Studia Islamica, 106(1), 102-123. https://doi.org/10.1163/19585705-12341254

Strohmaier, G. “Ḥunayn b. Isḥāḳ al-ʿIbādī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0300

Vadet, J.-C. (2012). “Ibn Māsawayh”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_3289

Veit, R. (2010). “Dāʾūd al-Anṭākī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, edited by K. Fleet, G. Krämer, D. Matringe, et. al. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_23481

Vernet, J. (2012). “Ibn al-Bayṭār”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_3115