We aim to re-imagine publishing, telling new stories of West Asia and its diasporas through essays and emerging research.

Launched in 2011, Ajam Media Collective is an online forum designed to highlight representations of West Asia within Western media.

Ajam started as a blog for graduate students with an interest in West Asia. This is the collective effort of five people from different fi elds, ranging from academia to filmmaking, music and journalism. By employing diverse skills and knowledge, they provide greater access to the more complex and nuanced discussions and debates within in the academy in the region, which they refer to as Ajamistan. The underlining premise is that this region, while part of the Middle East, is under-represented in Western and online media.

elds, ranging from academia to filmmaking, music and journalism. By employing diverse skills and knowledge, they provide greater access to the more complex and nuanced discussions and debates within in the academy in the region, which they refer to as Ajamistan. The underlining premise is that this region, while part of the Middle East, is under-represented in Western and online media.

Ajam in Arabic means ‘otherness’ and for this reason the term ‘Ajamistan’ was coined to refer to a geographical area from Turkey in the West and to Iran, the Caucasus, Central Asia, Afghanistan and South Asia in th e East. A common thread among these countries is the influence of Persianate culture and heritage present during the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal eras until the 18th to 19th centuries. In addition, since Persian was the language of culture and literature, these countries were influenced and continue to reflect various elements of Persianate culture.

e East. A common thread among these countries is the influence of Persianate culture and heritage present during the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal eras until the 18th to 19th centuries. In addition, since Persian was the language of culture and literature, these countries were influenced and continue to reflect various elements of Persianate culture.

“Ajam Media Collective is committed to uniting authors from various backgrounds and disciplines to promote diverse critical views on culture, politics, and society, emphasizing the region’s importance as a thriving cultural center whose multiple realities are too often obscured by the popular Western and global media.”

Therefore, this online platform focusses on  covering cultural and society related matters in this region, as well as shedding light on contemporary and historical issues via informed analysis, by offering semi-scholarly resources from academics, activists and student input. Ajam also provides access to contemporary research and debates in various topics, such as, Urban Geography, Cinema, Gender Studies, literature, history and others.

covering cultural and society related matters in this region, as well as shedding light on contemporary and historical issues via informed analysis, by offering semi-scholarly resources from academics, activists and student input. Ajam also provides access to contemporary research and debates in various topics, such as, Urban Geography, Cinema, Gender Studies, literature, history and others.

Moreover, in order to offer a holistic insight and to cover the respective topics comprehensively, a diverse range of formats are used to present various topics and insights, such as podcasts, longer essays of film analysis, photo essays, blog articles and music. This vast range of information can be accessed by region as well.

Moreover, in order to offer a holistic insight and to cover the respective topics comprehensively, a diverse range of formats are used to present various topics and insights, such as podcasts, longer essays of film analysis, photo essays, blog articles and music. This vast range of information can be accessed by region as well.

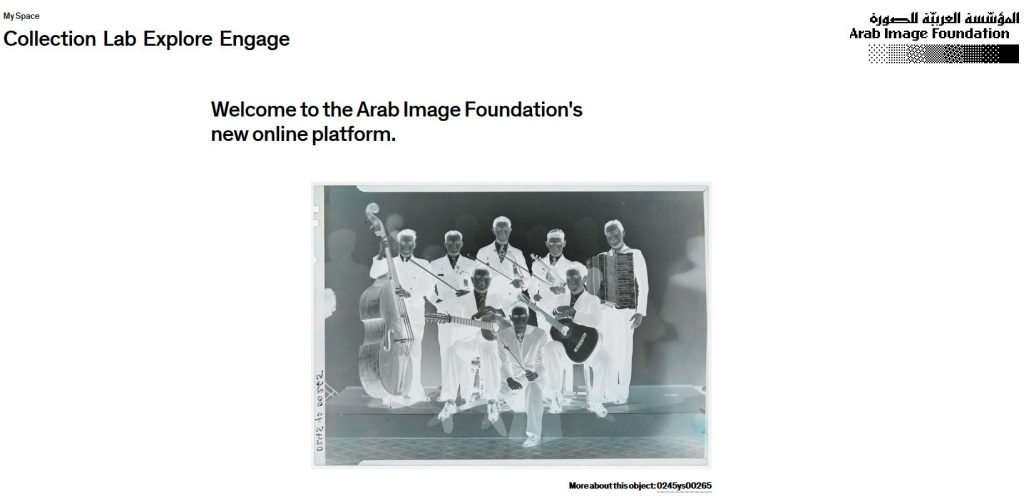

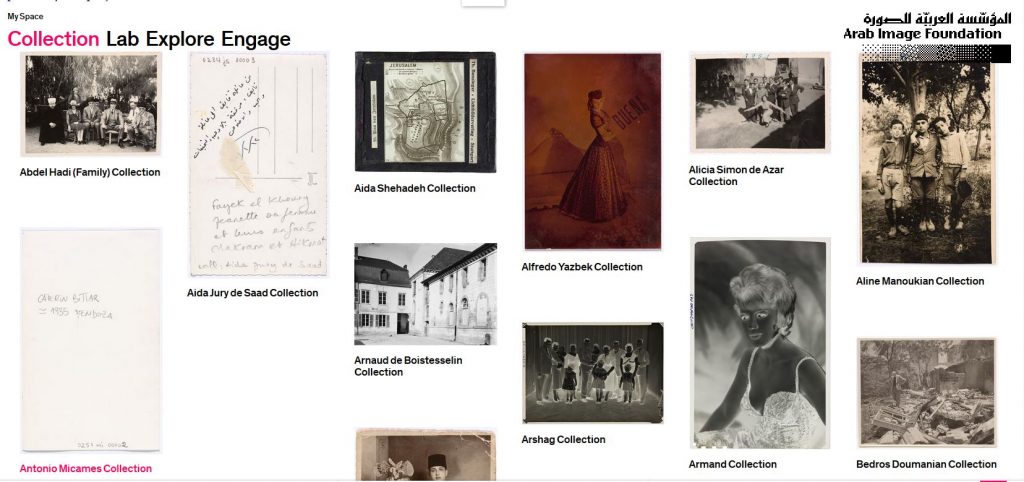

In 2016, the AIF embarked on a major drive to digitize its collection, which is housed in Beirut. Since then, 28,000 photographs from its collection have been digitized.

In 2016, the AIF embarked on a major drive to digitize its collection, which is housed in Beirut. Since then, 28,000 photographs from its collection have been digitized.

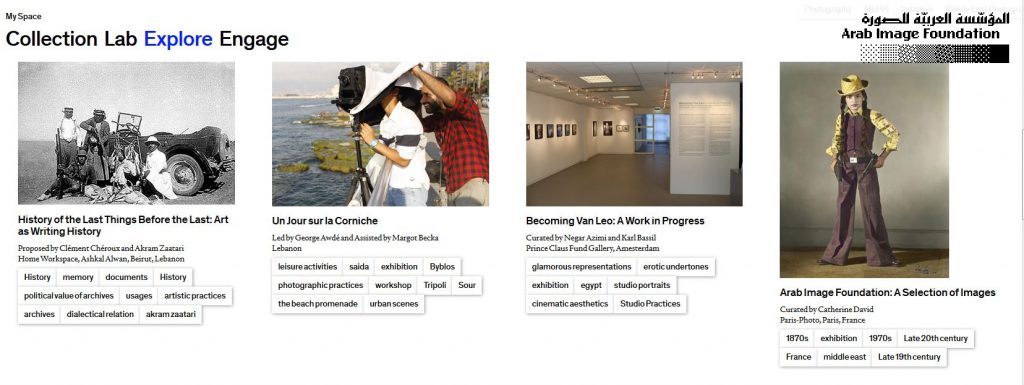

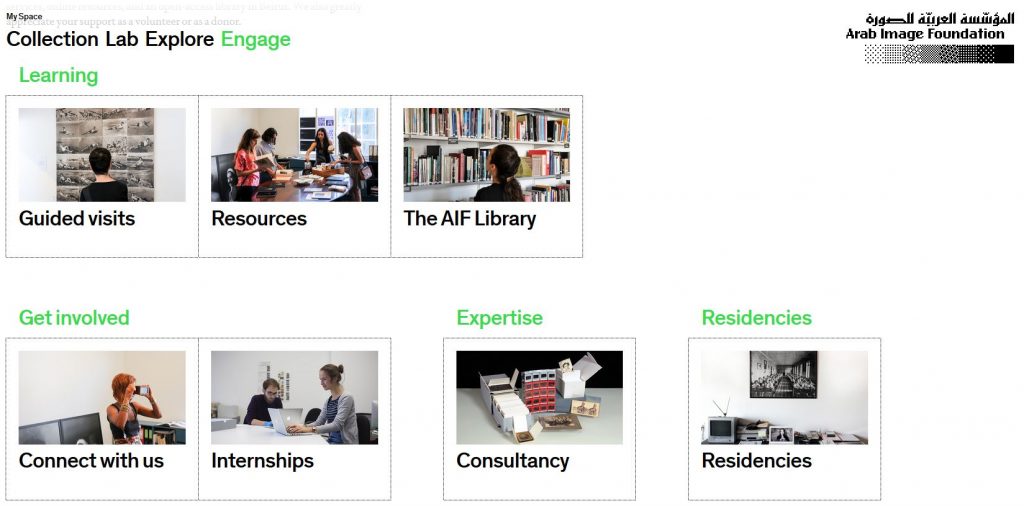

The Foundation hopes to generate critical thinking about photographic, artistic and archival practices, promoting its collection as a rich resource for research, reflection and the creation of new works, forms and ideas.

The Foundation hopes to generate critical thinking about photographic, artistic and archival practices, promoting its collection as a rich resource for research, reflection and the creation of new works, forms and ideas.