March 25th is Tolkien Reading Day – a day significant for marking the vanquishing of the Lord of the Rings (Sauron), the destruction of the ring, and the completion of Frodo’s quest. In honour of Tolkien Reading Day, check out the March Redpath Book Display, Talkin’ Tolkien, located in the Humanities and Social Studies Library! There you’ll find curated picks about Tolkien and linguistics, mythology, religion, and more.

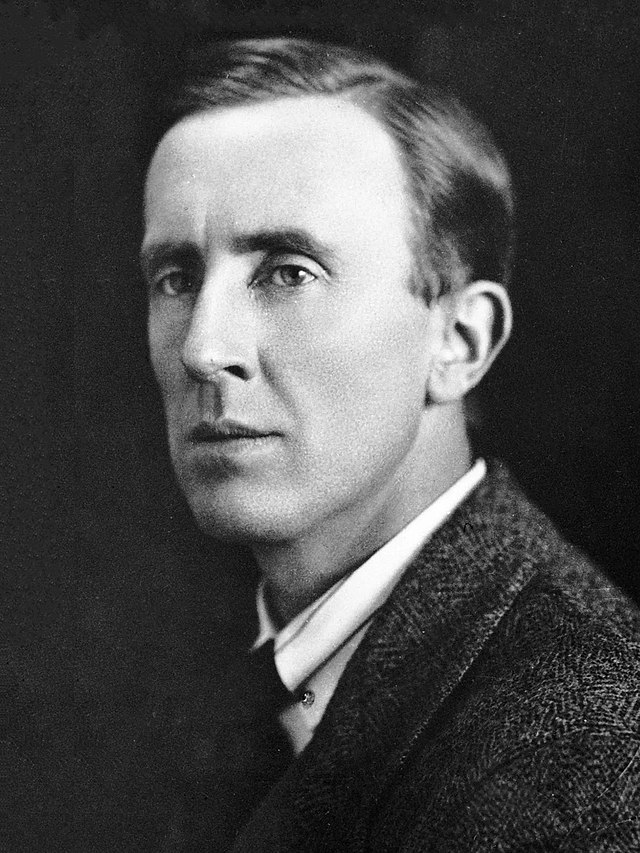

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born in 1892 in South Africa, moving to Birmingham, England at 4 years old. Tolkien, a name of German origin, means either foolishly brave or stupidly clever. Tolkien’s childhood home backed onto a railway yard, where his curiosity for linguistics took root as he saw trains bound for South Wales bearing names such as “Penrhiwceiber” and “Senghenydd.” At the very start of his career, Tolkien worked for Oxford English Dictionary – contributing to the definitions for “walnut,” “walrus,” and “wampum.” Throughout most of his adult life, Tolkien taught English literature and specialized in Old and Middle English. He studied and produced publications on works such as Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Along with C.S. Lewis, Tolkien was a part of the informal literary discussion group called the Inklings, which met at Oxford University over the course of the 1930s and 40s. He is most famous for being the author of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion (published posthumously by his son Christopher).

One of Tolkien’s earliest ambitions was to create a body of myth and legend for England. Being a devout Roman Catholic as well as a passionate scholar of world mythologies, he uniquely married Christian theology with paganism in his legendarium. This extensive collection of writings evolved over six decades of his life and the scope of his work is truly unparalleled.

Many of the names and story elements within the legendarium were influenced by Norse, Germanic, Finnish, and Celtic mythologies. The ring in the Norse Völsunga saga and the medieval German poem the Nibelungenlied are said to have inspired Tolkien’s one ring. However, the battle between good and absolute evil and the Christ-like sacrifice of Frodo are all thematically Christian. Although Tolkien avoids any explicit reference to religion or religious practice in the legendarium, he admits that the work is fundamentally religious and Catholic, but the religiosity is absorbed into the symbolism and grander story. Perilous Realms and The Ring and the Cross explore how Tolkien reconciled these two dichotomies amongst other complexities.

Tolkien was not only a prolific author, but also a linguist, and philologist– that is, a specialist in historical texts and languages. These academic interests informed his literary output: for instance, both the story of Isildur and the idea of the ‘Ring’ exist in 13th-century German literature, and the Rohirrim language is close to both Icelandic and Old English. Tolkien was fascinated by the construction of languages. He conceived the term “glossopoeia” and developed not one, but fifteen (15!) of the languages of Middle Earth. All of these languages are articulated together historically, and in Middle-Earth canon, all descend from the language of the Valar, the Gods. Tolkien put a great deal of effort into not only building structurally and grammatically cohesive languages but also creating the internal narratives and legends associated with these languages. He coined this idea “mythopoeia” (or “myth-making”): an invented language, to live, must be created alongside its history and stories.

An interesting tidbit here (for all the copyright enthusiasts in the room!) is that Tolkien’s languages – Quenya, Sindarin, Adûnaic – are his intellectual property, the rights of which passed to his estate. This means that Middle-Earth languages are copyrighted by the Tolkien Estate and can only be used with permission from the Tolkien Estate. There is an argument, however, that languages – once they are commonly used- cannot be copyrighted, and indeed a legal opinion published in 1999 noted (though not in a court of law) that under US copyright, systems cannot be copyrighted, and that an alphabet is a system. That being said: there has (so far) not been any court case where the Tolkien Estate has attempted to assert their rights to Elvish use, and there is a shared agreement that scholars and enthusiasts can disseminate information about Elvish, as long as no profit is being made, on sites such as elvish.org.

Many younger fans may have been introduced to Middle Earth through Peter Jackson’s film adaptations of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit – did you know that the library not only has DVD/Blu-ray copies of these, but they are also accessible (except the third Hobbit movie) through the free streaming service Criterion? Must be time for a movie marathon! If you’re interested in the reception of The Hobbit trilogy, you can check out Fans, Blockbusterisation, and the Transformation of Cinematic Desire: Global Receptions of the Hobbit Film Trilogy available by eBook through McGill Library.

Indeed, the world’s love of Tolkien is alive and well in the 21st century – there’s a (paid) app called Walk to Mordor that allows you to track your steps as you recreate Frodo’s journey to Mordor. For further immersion, check out the fan project “Minecraft Middle Earth” which has ambitiously set out to produce a faithful reproduction of Middle Earth in the hit videogame Minecraft. That’s a lot of blocks!

The book display and this blog post was curated by the Graduate Student Reference Assistants: Jenna Coutts, Lise Bourbonniere, Marianne Lezeau and Sarah Wood-Gagnon