By Claire Grenier

This post is about the current display in the Redpath Library Exhibition Case, curated by IMPRESS intern Claire Grenier. The Indigenous Stories Exhibition will be on display in the library until the end of September.

The only accurate way to title this display was Indigenous Stories. For Indigenous cultures oral traditions and storytelling are integral to our preservation. In this display I have tried to pull a variety of these stories from varied sources and disciplines. The selections include theory, non-fiction, fiction, poetry, art, plays, graphic novels, vintage dictionaries, decolonial guides… all of which demonstrate the ongoing scope of Indigenous talent. I also wanted to offer up explanations on the Indigenous land on which McGill occupies and information on the three distinct Indigenous groups in what we call Canada. First Nations, Inuit, and Métis all have unique histories and practices which contribute to the diverse makeup of Indigenous people from coast to coast to coast. Short explanations of the land and the Indigenous groups within Canada are dispersed through the display and also available here:

“McGill University is on land which has long served as a site of meeting and exchange amongst Indigenous peoples, including the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabeg nations. We acknowledge and thank the diverse Indigenous peoples whose presence marks this territory on which peoples of the world now gather.”

McGill must pursue an unedited truth about its historical and contemporary relationship with First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples to meaningfully inform its goal of reconciliation.

As Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Report emphasized, reconciliation must begin with the truth. This must include proper and ongoing consultation with Indigenous peoples, and the recognition of the Indigenous traditional territory upon which McGill is situated.

Who are the First Nations?

First Nations have existed on the land we now call Canada since time immemorial. There are over 600 nations and 50 languages across Turtle Island, each with unique histories, traditions, and practices.

Who are the Inuit?

Inuit have lived and thrived across Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit homeland encompassing 36 per cent of Canada’s landmass and 50 per cent of its coastline. The four regions include Nunatsiavut, Nunavut, Nunavik, and Inuvialuit.

Who are the Métis?

The Métis are a post-contact group descended from European men and Indigenous women along the routes of the fur trade who created a distinct culture and language. The Métis settlements span across the prairies and parts of Ontario and British Columbia. The Métis have fought for centuries for their rights and recognition.

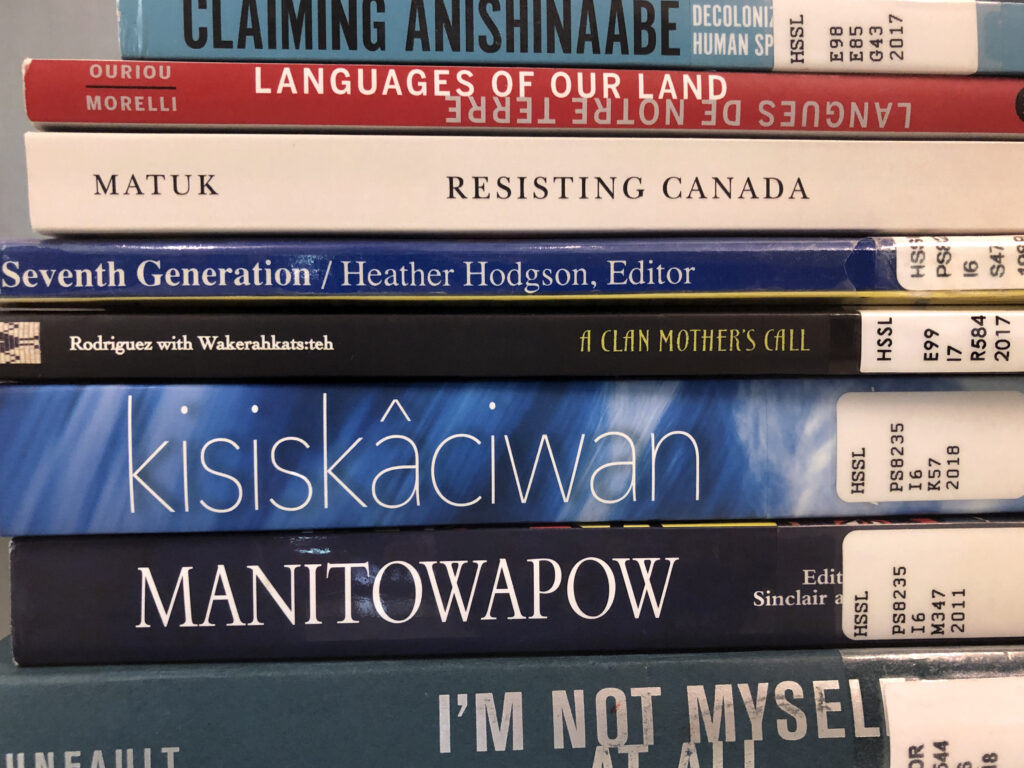

Indigenous Stories Book Display

Now I would like to discuss some of the featured works in the display.

The first feature is a book called Àbadakone, which is based on a celebrated exhibit in The National Gallery of Canada which opened in the Fall of 2019. This book features over 70 artists’ work from the exhibit, including those of the McGill Indigenous Studies and Community Engagement Initiative (ISCEI) 2021 and 2022 artists-in-residence Caroline Monnet and Danya Danger. The other art book on display is Desire change : contemporary feminist art in Canada, which is open to a photograph of Anishinaabekwe artist Rebecca Belmore’s 1991 piece Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother.

The next spotlight belongs to the 2021 ISCEI writer in residence, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. There are several works by Simpson in the display, the most prominent one being Noopiming: the cure for white ladies. The cover features anther work of Belmore’s – an installation piece from 2008 called Fringe. “Noopiming” is Anishinaabemowin for “in the bush.” Simpson chose this title as a direct response to Canadian settler author Susanna Moodie’s 1852 memoir Roughing it in the bush. As a novel, Noopiming takes place in the same time as Moodie’s memoir providing a cure for “Moodie’s racist treatment of Mississauga Nishnaabeg in her writing” (book listing). Simpson is one of the most clever Indigenous contemporary writers working today. Another of her books included in the display is A short history of the blockade: Giant beavers, diplomacy, and regeneration in Nishnaabewin. Portions of this book made up Simpson’s 2020 Kreisler lecture at the University of Alberta. The lecture, The Brillianchttps://youtu.be/8Jbp7uzj_YMe of the Beaver: Learning from an Anishnaabe World, has been integral to my own practice as an Indigenous academic and knowledge seeker in addition to influencing the structure of this display. In her lecture, Simpson explains that:

My people are constant storytellers throughout the day and throughout the seasons. Stories are the fabric of daily life. My ancestors woke up each morning and created an Anishnaabe world. They animated their political system of governance and diplomacy. They built their collective philosophical and ethical understandings. They made processes for solving conflicts and reestablishing balance. And they built their economy with the consent of plant and animal nations. They built, maintained and nurtured systems for sharing knowledge and taking care of each other. They worked collectively to produce, reproduce, replicate, amplify and share Indigenous life because if they did not, Anishinaabe worlds wouldn’t exist.

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, “The Brilliance of the Beaver: Learning from an Anishnaabe World”, CLC Kreisel Lecture (University of Alberta), March 12, 2020, link.

The next major grouping of works in the display fall under the category of knowledge keeping and evaluation. These books range from environmental theory to classic surveys of methodology. Given the spotlight here is Margaret Kovach’s revolutionary work Indigenous Methodologies. This book was one of the first of its kind in the field. In it, Kovach expresses the necessity of storytelling to the practice of Indigenous research. “By listening intently to one another, story as method elevates the research from an extractive exercise serving the fragmentation of knowledge to a holistic endeavour that situates research firmly within the nest of the relationship” (98).

Many of the environmental texts selected for the display follow this principle too. Climate change: linking traditional and scientific knowledge (2006, edited by Roderick R Riewe and Jill E Oakes), Ancient pathways, ancestral knowledge: ethnobotany and ecological wisdom of Indigenous peoples of northwestern North America (2014, edited by Nancy J Turner), and When the caribou do not come: Indigenous knowledge and adaptive management in the western Arctic (2018, edited by Brenda Parlee and Ken J Caine) all use Indigenous stories and practice to open up a dialogue with climate and environmental scientists to see how their history and experiences can help combat the ongoing climate crisis.

The most personal work I chose for the display is Chester Brown’s 2003 “comic-strip biography” Louis Riel. The subject of Brown’s book, Louis Riel, was the leader of the Métis’ Red River Resistance. For Métis like me, Riel is not just a hero, he is the reason that we are recognized as a distinct group. In the eyes of many Canadian settlers, he is a “traitor” who deserved his sentence of hanging for treason. Chester Brown shows these settlers the passion, drive, and charisma of Riel and the sacrifices and battles he fought for his people. I read this book for the first time when I was 12 after my 7th grade teacher insisted that Riel had been a traitor not a martyr. It was one of the first times I remember feeling connected to my history outside of the semi-annual Harvest Dinners hosted by my local Métis organization. Riel made it possible for the Métis to not only exist, but to be constitutionally recognized as we are today. Riel believed that “we must cherish our inheritance. We must preserve our nationality for the youth of our future. The story should be written down to pass on.”

Also featured in the display is another graphic novel: Moonshot which is a collection of Indigenous comics edited by Elizabeth LaPensee and Michael A Sheyahshe and published in 2020. This particular volume focuses on how Indigenous futurism interacts with traditional knowledge and culture. Some equally fun picks are the two works which highlight two-spirit and indigiqueer identity. Two-spirit acts: queer Indigenous performances, which was edited by Jean Elizabeth O’Hara and features one-act plays by Waawaate Fobister, Muriel Miguel, and Kent Monkman, provides space in the genre of theatre to openly and unapologetically explore what it means to be queer and Indigenous. Similarly, Joshua Whitehead’s 2017 work of poems, Full-metal Indigiqueer “focuses on a hybridized Indigiqueer trickster character named Zoa who brings together the organic (the protozoan) and the technologic (the binaric) to re-beautify and re-member queer Indigeneity.”

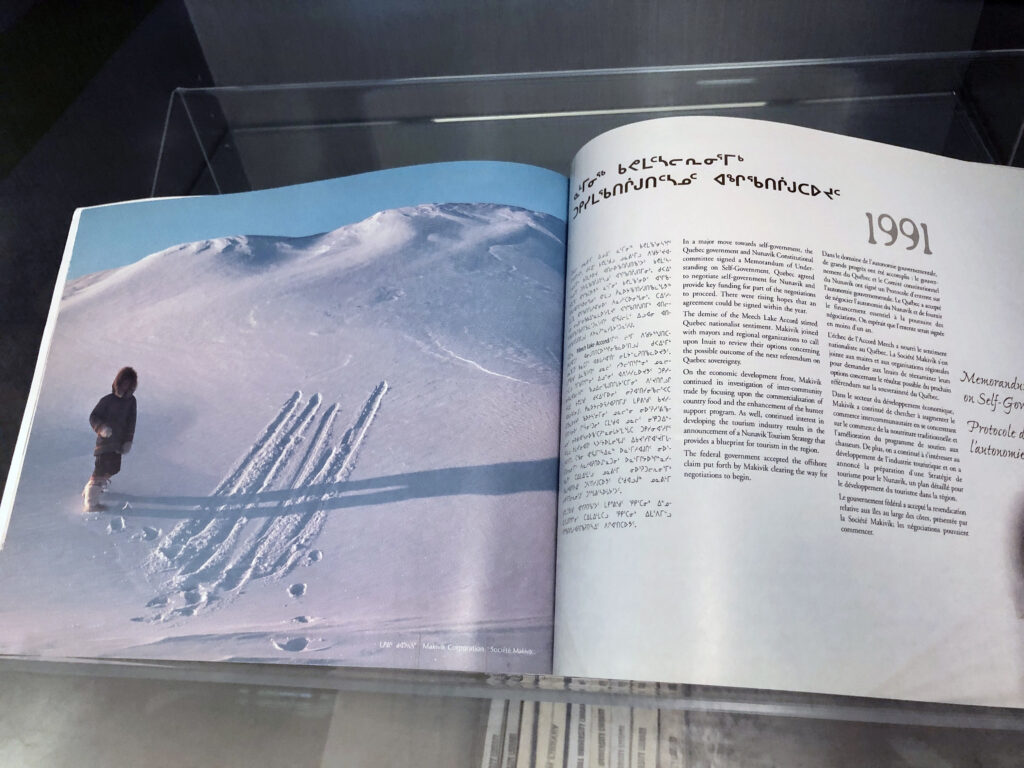

There are also selections in the display which are specific to Inuit culture, history, and future. Amun is a collection of Inuit poetry in French and features work from ISCEI’s 2022 writer in residence Maya Cousineau-Mollen. There is also a special photo book used in the display which depicts life in the north. Arraaguit 25 nalliutivut taimanngat Jaims Pai ammalu Kupait tarranga angirkatigiigutaulilaursimatillugit is a celebration by the Makivik corporation for the 25th anniversary of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement.

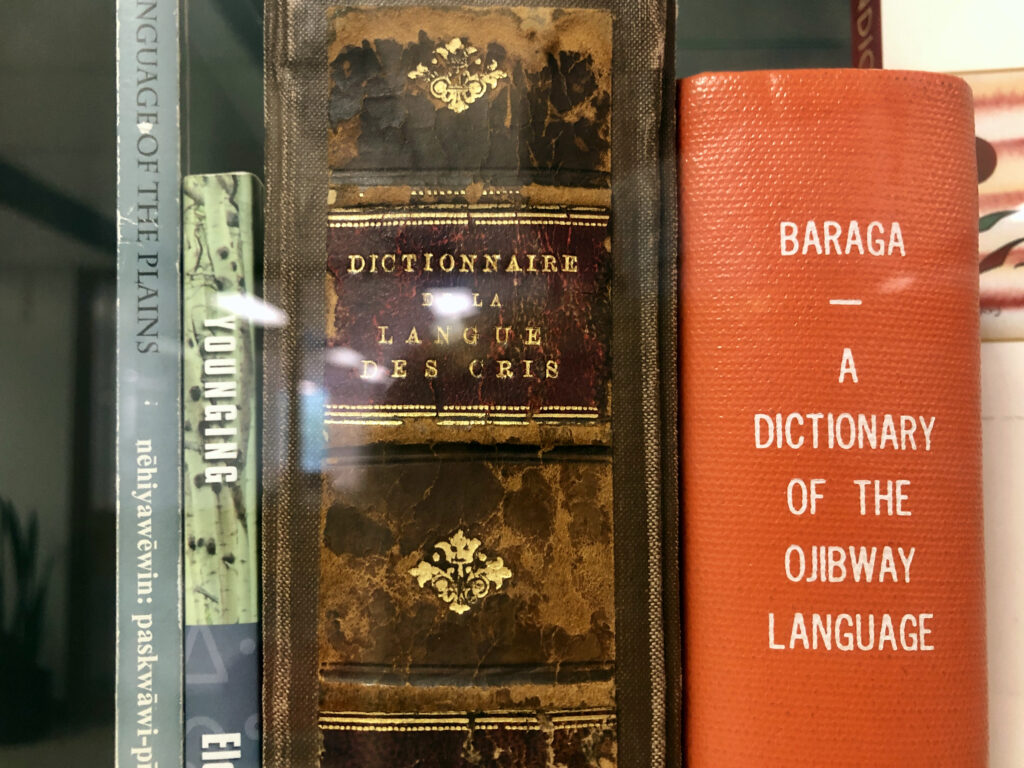

Lastly, I would like to turn to one of my favourite things I encountered while putting this display together. The piece in this display which I find the most interesting is not by an Indigenous author, but by a 19th century French missionary. It’s a French/Cree dictionary from 1874. The author of the dictionary is Albert Lacombe, one of the best-known missionaries in Canada’s history. Lacombe had a special interest in evangelizing the Cree and Blackfoot populations in Canada’s west. To do this, he needed to understand the language. For me, the reason this dictionary is so interesting is because it is such a clear tool of colonialism, yet it is also casual. While it’s just a dictionary, the reason why Lacombe created a dictionary of French to Cree was to more effectively convert and colonize Indigenous peoples. It’s a symbol of the power of language, of how for so long outsiders learning Indigenous dialects did so with malicious intent and with the goal of having not just the language, but the ways of life, erased and replaced with Western ideals.

This dictionary holds so much tragedy and history, and it was just sitting in the stacks of McLennan! In my last two months at the library, the discovery of this dictionary helped me explore an integral line of inquiry for my work as a Métis academic: who decides which knowledge and stories are worth keeping record of?

Through this display I’ve tried to curate a selection of many different Indigenous stories currently held by the library. By putting all these different works from different fields on an equal footing I hope I have shown you the diversity of Indigenous knowledge and convinced you of the importance of preserving all these stories, including the ones of trauma, and especially the ones about joy.

Maarsi

All of the books in Claire’s Indigenous Stories book display can be found on this booklist.