by Jessica Lange, Scholarly Communications Librarian

Thinking about using open textbooks this fall?

3 easy steps: Find, Evaluate, Use!

The drastic shift to online in higher education has a lot of professors rethinking their instruction methods as well as their course materials. Substituting online materials for print, is becoming an attractive option.

Locating and using open content doesn’t have to be hard and the Library is there to support you along the way.

- Find

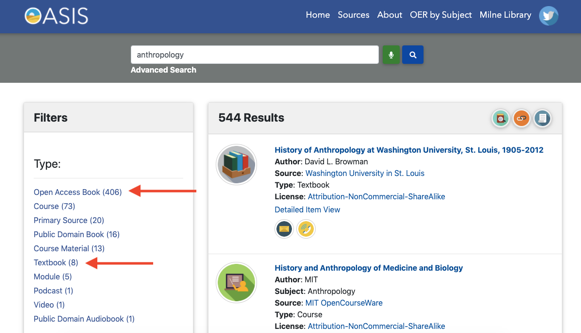

- SUNY has created a search engine dedicated to open textbooks and related materials. It’s a great place to start: https://oasis.geedu/

- Tip: Search and then limit to ‘open access book’ or ‘textbook’

- Evaluate

- BCCampus has developed a great checklist for assessing an open textbook:

- Use

Can’t find content for your course or subject area? Don’t hesitate to contact your liaison librarian.

Frequently-Asked Questions

- Won’t I be infringing on copyright if I use these materials?

- No. Open textbooks are licensed to allow reuse. The terms of the individual licenses will vary (see our guide Understanding licenses and copyright).

- What is the quality of these materials?

- As with any publication, quality will vary. However, many open textbooks are developed through rigorous peer review and production processes that mirror traditional materials. It is important to note that being open or closed does not inherently affect the quality of a resource.

- Do open textbooks require special technology to use?

- No. One of the great things about open textbooks is that users have the right to turn it into any format they wish (which is almost always forbidden with traditional resources). Therefore, open textbooks aren’t tied to a particular type of device or software, which gives students and schools more freedom in what technology they purchase. In cases where technology isn’t available, there is always the option to print.

- Does using open textbooks affect student learning?

- Studies to date have not shown a negative effect on student learning. A good summary of current research can be found on this guide.

- How do you tell if an educational resource is an open textbook?

- The key distinguishing characteristic of an open textbook is its intellectual property license and the freedoms the license grants to others to share and adapt it. If a book is not clearly tagged or marked as being in the public domain or having an open license, it is not open. It’s that simple. The most common way to release materials as open textbooks is through Creative Commons copyright licenses, which are standardized, free-to-use open licenses that have already been used on more than 1 billion copyrighted works.

- What is the difference between ‘free’ and ‘open’ resources?

- Free resources may be temporarily free or may be restricted from use at some time in the future (including by the addition of fees to access those resources). Moreover, free-but-not-open resources may not be modified, adapted or redistributed without obtaining special permission from the copyright holder.

FAQs adapted in part from SPARC’s FAQ: Open Educational Resources (Creative Commons Attribution (CCBY) 4.0 International License)

See also: McGill Library Open Textbooks guide.