- Tell us a little about yourself. (Background, field of research, etc)

I work on pre-modern traditions of commentary in two fields: commentaries written on the Qur’an, a genre called tafsīr, and commentaries on works of balāgha, a field that encompasses aspects of Arabic linguistics, stylistics, and literary theory. The bulk of my research is in the period widely referred to in Islamic studies, for better or for worse, as the post-classical period, covering from around the twelfth century to modernity. I work on the content of commentaries from this period, as well as broader questions related to the history and development of that genre of writing, and the scholarly cultures and environments in which such practices of writing emerged. Much of the scholarly output from that period remains extant in manuscript form, and even when the works are published, their manuscripts contain a wealth of other types of information that is invaluable for reconstructing intellectual history. That is a roundabout way of saying that I also work quite a bit with manuscripts.

a. Follow up question: what drew you to this area of research?

I find commentary writing fascinating, especially in the fields of tafsīr and balāgha. The nature of commentary writing is that it is integrative, meaning that it brings in a number of other disciplines to bear on whatever it is discussing. In many ways, commentaries reflect the latest in the field from a variety of disciplines in the pre-modern period. As you get into more expansive commentary literature, you start to see what pre-modern scholars thought was the horizon of interpretive possibilities when it came to language use. Oftentimes – not always – you find that what they have to say about the Qur’an and language interpretation is directly relevant to theories that are being offered on these topics today.

I have long been interested in the language and style of the Qur’an, as well as issues related to how language is interpreted. How the Qur’an is and/or ought to be interpreted is of course a continuing matter of debate outside of academic circles. When I was an undergraduate, I began to write papers on some aspects of Qur’anic style, and I drew on the Qur’an commentary tradition, the natural place to look for insight on those matters. I wrote a paper on Qur’anic rhyme, and another paper on Qur’anic humour. Neither of those papers were very good, but both of them inform a larger project I am now working on related to the intertwined development of balāgha and tafsīr. It is nice to see these undeveloped ideas turn into something substantial much later. Sometimes you don’t know how what you are researching will come together or show its importance later.

I would go on to receive substantial training in reading commentaries. After my MA, I moved to the Middle East, where I was trained for many years in the close reading of a range of texts, including some texts in tafsīr and balāgha, and related fields like grammar, and made use of commentary and supercommentary writing, the latter being commentaries written upon commentaries. This was invaluable training for me because this type of close attention is a feature of traditional Islamic pedagogy and requires a large time investment from the end of both student and teacher. I am very grateful for those who invested substantial amounts of their time in me. I was able to study some medieval handbooks word for word, like al-Taftāzānī’s Mukhtaṣar al-maʿānī, a fourteenth century primer in balāgha that was central to balāgha and tafsīr. It engendered its own commentary tradition, and it is still studied to this day. That book is also an important piece of the research I do today. That kind of training had – and continues to have – a significant impact on my ability to read and engage with the texts in my field, and it also shaped how I think about the traditions from which those works derive.

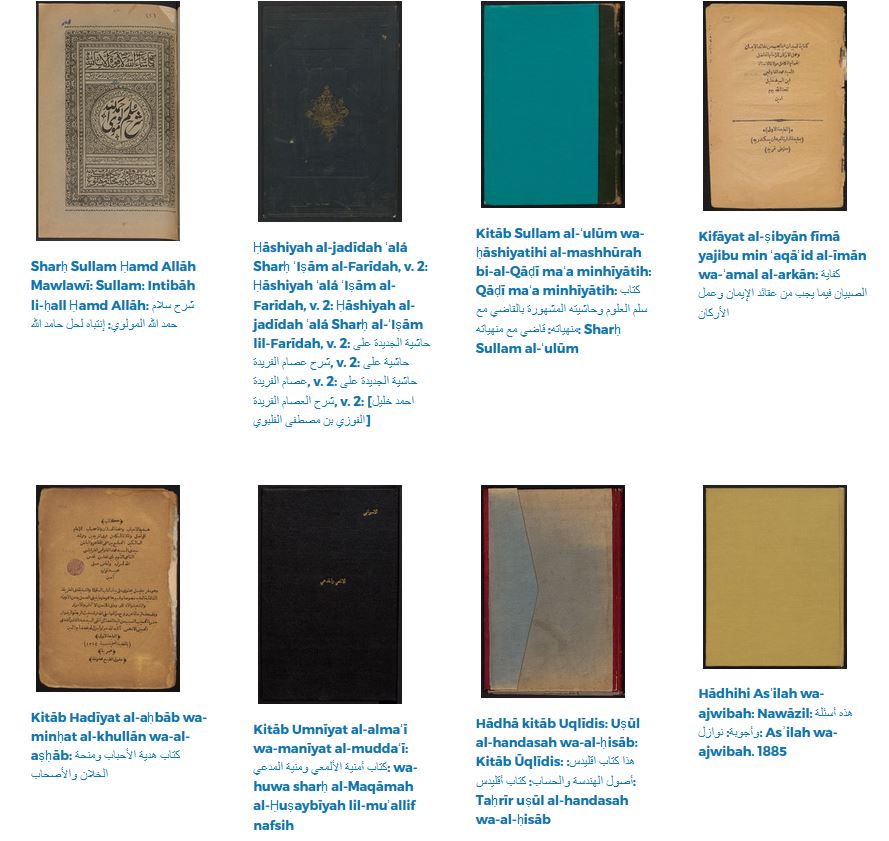

I am also drawn to these areas of research precisely because they are under-researched. This is in part because scholars have long been interested in origins in Islamic studies. As a corollary, works from later times have often been depicted as originating from a period of decline, and stamped by their period. For these reasons, most of the works in what we can call the post-classical period have received little to no attention. Just as an example, even though the Mukhtaṣar I just mentioned was central for hundreds of years, and even though there is probably no major manuscripts library without a copy of this work, if not dozens of copies, there is nothing substantial written on it in the western academy. This, at least to me, creates this strange dissonance in how we present and engage with the past, where works like this that were clearly important are understudied, while other works which were relatively less important enjoy the continued attention of scholars today. Even worse, the ideas and theories that developed in this long period of scholarship remain relatively unknown, which creates its own host of problems. For example, sometimes the same theories are assumed to have no precedent and are simply replicated today. The long and the short of it is that because of my training in these areas, I want to make substantial contributions to our knowledge of two fields which are critical and have relevance today but remain understudied.

I should say something about manuscripts. Using manuscripts is unavoidable in the field because so much of the heritage of Islamic scholarship is available only in manuscript form and restricting yourself to printed works severely limits the scope of your scholarship. Even before any type of formal training in manuscripts, I was using manuscripts for research or just for interest. A lot of the time when I would look for a book, its manuscripts would come up in internet searches; someone had helpfully uploaded a copy to some internet forum or site. Some of those forums have unfortunately gone defunct and have been replaced to varying degrees with other sites or types of social media. In my undergrad and MA, I started to work on some of Walid Saleh’s manuscripts projects related to tafsīr, and that was my first formal training in that area. For example, I read with him the entirety of a treatise he was editing by a Mamluk scholar named al-Biqāʾī, and did some work for Professor Saleh on the introduction another scholar, al-Aṣfahānī, wrote for his tafsīr. During my PhD, I worked on another manuscripts project with him; we edited a lacuna that was missed in a recent printed edition of an eleventh century tafsīr work by al-Wāḥidī. I also worked on a manuscripts project for Jeannie Miller on using marginalia in manuscripts of al-Jāḥiẓ’s Kitāb al-Ḥayawān, or Book of Animals, to trace the transmission of that work. That project informed some of the focus on paratexts in my dissertation. Those were some of the influences in my work on manuscripts.

2. What can you tell us about your dissertation?

I wrote my dissertation at the University of Toronto, although from home would probably be more accurate, because I actually researched and wrote it almost in its entirety during the worst of the pandemic. I had received a grant from U of T to do some manuscripts research at the Süleymaniye library in Istanbul, which I did for a couple of months in the fall of 2019. When I was there, I looked at manuscripts of the two main works of an eleventh century grammarian, ʿAbd al-Qāhir al-Jurjānī, his Dalāʾil al-iʿjāz (Markers of Inimitability) and his Asrār al-balāgha (Secrets of Eloquence), because I was working on ʿAbd al-Qāhir for a larger project. During the pandemic, in the Spring of 2020, I began to work on these manuscripts in earnest, thinking that the research on their paratexts would result in an article. But that one article became two, then morphed into three, and then I realized I had a whole new project. I think that’s probably a common experience for scholars doing continued research in the humanities. And that became my dissertation. It recently won the Malcolm H. Kerr dissertation award, honorable mention for the humanities.

The dissertation itself was meant to show how we can trace an intellectual history, in this case primarily related to balāgha and tafsīr, through the use of paratextual material. In this case, I made use of paratexts, here meaning any written material other than the main text itself, taken from over thirty manuscript copies of ʿAbd al-Qāhir’s works. ʿAbd al-Qāhir’s works, especially the Dalāʾil, were foundational for the emerging discipline of balāgha. They would serve as the basis for later textbooks and commentaries in that field.

I used paratextual evidence – ownership notes, colophons, and substantive marginal notes written by scholars who owned copies of his works – to show how these classic works were not lost, as is sometimes claimed, but were rather used, engaged with, and reintroduced throughout the postclassical period up to the modern era. In a specific sense, my dissertation was about these two works, and balāgha and tafsīr, and commentary writing in the post-classical period. However, because I was primarily using paratextual evidence, the project was in a larger sense about broader concerns in book history, scribal and scholarly communities, and intellectual history.

3. What are you working on right now, any specific project?

I have a few projects occupying me. I am currently working here at McGill on the tradition of supercommentary writing on the Qur’an and what it meant to practice Qur’an commentary by the seventeenth century in the pre-modern period. Supercommentaries, by this time, had become a massive endeavour and had become their own genre of writing: they had their own set of concerns and references. I am working on a type of pre-modern footnoting, which is one strategy to manage the information in these large projects. I discovered this strategy in manuscripts of a supercommentary in tafsīr by a seventeenth century scholar, Shihāb al-Dīn al-Khafājī, who wrote his commentary on the tafsīr of al-Bayḍāwī, a fourteenth century scholar. This dovetails nicely with my dissertation, because supercommentary writing is part of that engagement with ʿAbd al-Qāhir, and also because Shihāb al-Dīn al-Khafājī, coincidentally, is one of the most famous owners of ʿAbd al-Qāhir’s works. I am also working on a monograph that traces the interrelated history of balāgha and tafsīr, with a focus on some broader issues, including verbal irony and rhyme in the Qur’an. That is a project that focuses on the content of the commentary and supercommentary traditions in those disciplines, and so it complements the focus on paratexts in my other project. Finally, I am working on revising my dissertation into a monograph for publication.

4. Is there anything else you would like to share with us?

I received a grant from the Max Weber Foundation to do some manuscripts research this year in Italy, Istanbul, and India, so I am very excited about that. I am presently in Rome now. I saw a massive flock of starlings swarming by the Vatican, which was my first time seeing that. It’s spectacular! I am examining copies of commentary works in my two primary fields for their paratextual evidence. I am optimistic that they will contain a wealth of evidence useful for reconstructing how these works were transmitted and used. In general, I hope that even more scholars will study the content of commentary writing and manuscripts from this period. It is mostly untouched material, and there really is no shortage of amazing discoveries awaiting the unsuspecting researcher.

At the end, we would like to thank you for participating in this interview for the library blog, this is greatly appreciated. And we wish you the best of luck in all of your endeavors!

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the Islamic Studies Library nor McGill University

2. The

2. The