Welcome back! As an introduction, or reintroduction, to your friendly, neighborhood history of medicine library, here are some questions I get asked frequently in the tours and classes I do here in the library. I’ve answered them here for your enjoyment and edification!

Do people actually use the books here?

Absolutely! We have lots of readers come in to consult our rare books and archives, from various levels and fields. Many McGill profs use our collections in their research and McGill students use them for theses and research projects. We also receive visiting scholars from all over, some of whom are winners of our travel grants. You are not required to show academic credentials to use our collection, but if you are unused to working with fragile rare items, we will instruct you in how to use them in a way that doesn’t damage the books and contribute to their deterioration. Please feel free to write to us about your research project and make an appointment to consult our materials.

Absolutely! We have lots of readers come in to consult our rare books and archives, from various levels and fields. Many McGill profs use our collections in their research and McGill students use them for theses and research projects. We also receive visiting scholars from all over, some of whom are winners of our travel grants. You are not required to show academic credentials to use our collection, but if you are unused to working with fragile rare items, we will instruct you in how to use them in a way that doesn’t damage the books and contribute to their deterioration. Please feel free to write to us about your research project and make an appointment to consult our materials.

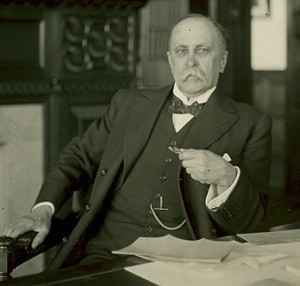

How did William Osler manage to collect all these books? Was he ridiculously wealthy?

From the William Osler Photo Collection.

Osler was a successful doctor, but certainly didn’t have the means it would take to accumulate a comparable collection today. 19th century physicians were generally paid according to what we would call a sliding scale. And since Osler was a famous physician in his day (he wrote one of the most famous medical textbooks), he had many well-to-do patients who remunerated him accordingly. Still, his love of books was so overwhelming that he describes in letters borrowing money from a rich brother to pay for his habit. Beyond that, though, the end of the 19th century and before WWI was something of a golden age for book collectors—rare books were still pricey items, but not nearly as expensive as they are today.

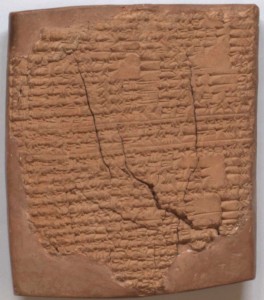

What is your oldest book?

Our oldest “book” is actually a clay tablet, probably written sometime during the 8th century BCE in Assyria (an ancient kingdom in modern day Iraq). The tablet is an example of one of the earliest forms of writing, done by forming tablets out of clay, impressing letters into them with a sharpened stick (called a stylus) in an alphabet called cuneiform, and letting the tablets bake in the sun so the writing is fixed. This tablet lists medical recipes made out of plants and animals. Here’s one particularly appealing example, a treatment for eye problems: “slay a scorpion, pull out its tongue, cut off its head, and with its blood anoint the inflamed eye; [the patient] will live.”

What is your most expensive book?

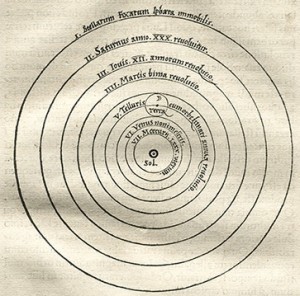

Copernicus (1473-1543), De Revolutionibus orbium coelestium (The Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), Nuremberg, 1543. B.O. 566. Woodcut f.9v depicting the heliocentric model.

It’s hard to say exactly, but this might be a contender: have a look at what this first edition copy of Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres sold for at auction last year. We also have a first edition of this 1543 work in which Nicolaus Copernicus, the famous Polish Renaissance astronomer, describes for the first time in modern history the revolution of the planets around the earth. The Ptolemaic, or geocentric, model of the universe that dominated scientific had by the Renaissance period become extremely mathematically complicated in order to explain the movement of the planets that had been observed and recorded for generations. In this book, Copernicus demonstrated that his heliocentric model could simply and elegantly explain planetary motion.

Why is there one window in the stained glass that is different from the others?

Good question! This window was designed along with the rest of the Osler Room by Montreal architect Percy Nobbs in the 1920s. It features two symbols with medical significance. First is the staff of Asclepius, the Greek patron god of medicine. Asclepius was thought to be a son of Apollo. Temples to Asclepius were found throughout the classical world, and sick petitioners would visit them to sacrifice to the god, spend the night in the temple’s inner sanctum, and receive ritual healing from the temple priests. The symbol’s serpent and staff are thought to represent healing and rejuvenation. The second symbol is a book held out by a heavenly hand. The book represents the university, learning, scholarship, and the idea of medicine as knowledge transmitted through the ages. So why is there one book that has no writing on it? What do you think: mistake or message?

Why aren’t you wearing white gloves?

Generally, it’s no longer the accepted practice in the rare books world to wear white gloves when handling materials, except in some particular cases (like delicate photographs). The theory behind gloves was that the natural oils on peoples’ fingers would wear down the books over time. This may be true (we still try to avoid touching the written and printed text itself and only touch the blank margins of a book’s pages), but it’s counterbalanced by the fact that pages are a lot harder to turn in bulky gloves and the risks of tearing a page are a lot higher. Better to just come with clean hands.

Generally, it’s no longer the accepted practice in the rare books world to wear white gloves when handling materials, except in some particular cases (like delicate photographs). The theory behind gloves was that the natural oils on peoples’ fingers would wear down the books over time. This may be true (we still try to avoid touching the written and printed text itself and only touch the blank margins of a book’s pages), but it’s counterbalanced by the fact that pages are a lot harder to turn in bulky gloves and the risks of tearing a page are a lot higher. Better to just come with clean hands.

Are Osler’s ashes really there?

Yes. But no, sadly, you can’t see them.