Guest post by Patrick Outhwaite. Patrick is a PhD candidate at McGill University in the department of English under the supervision of Professor Michael Van Dussen. He holds an MSt in Medieval Studies from the University of Oxford, and an MA in Medieval English from King’s College London. In 2015-16 he was a placement student at the Wellcome Library. His research interests include the interplay between medieval theology and medicine, as well as palaeography.

La version française suit

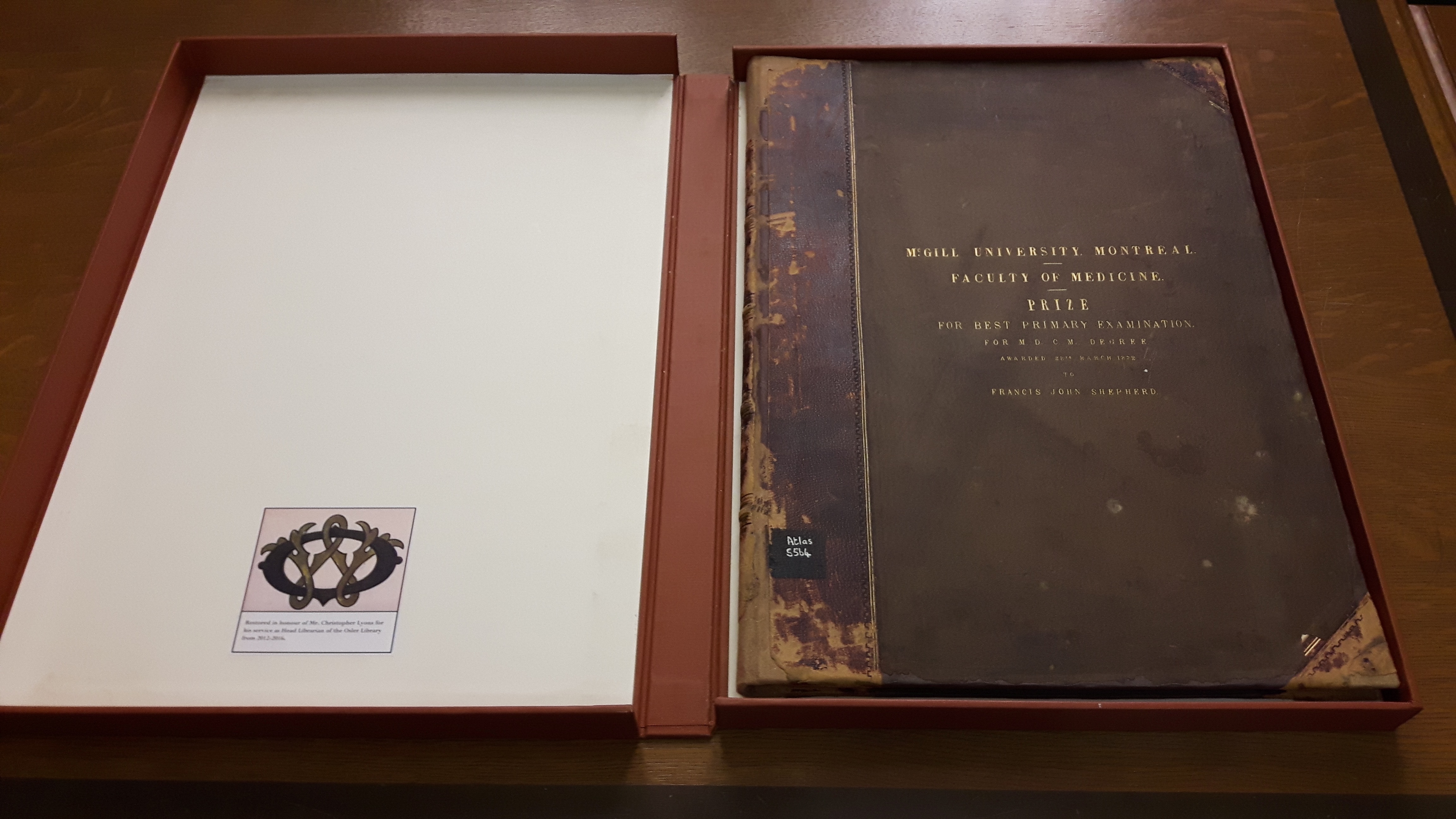

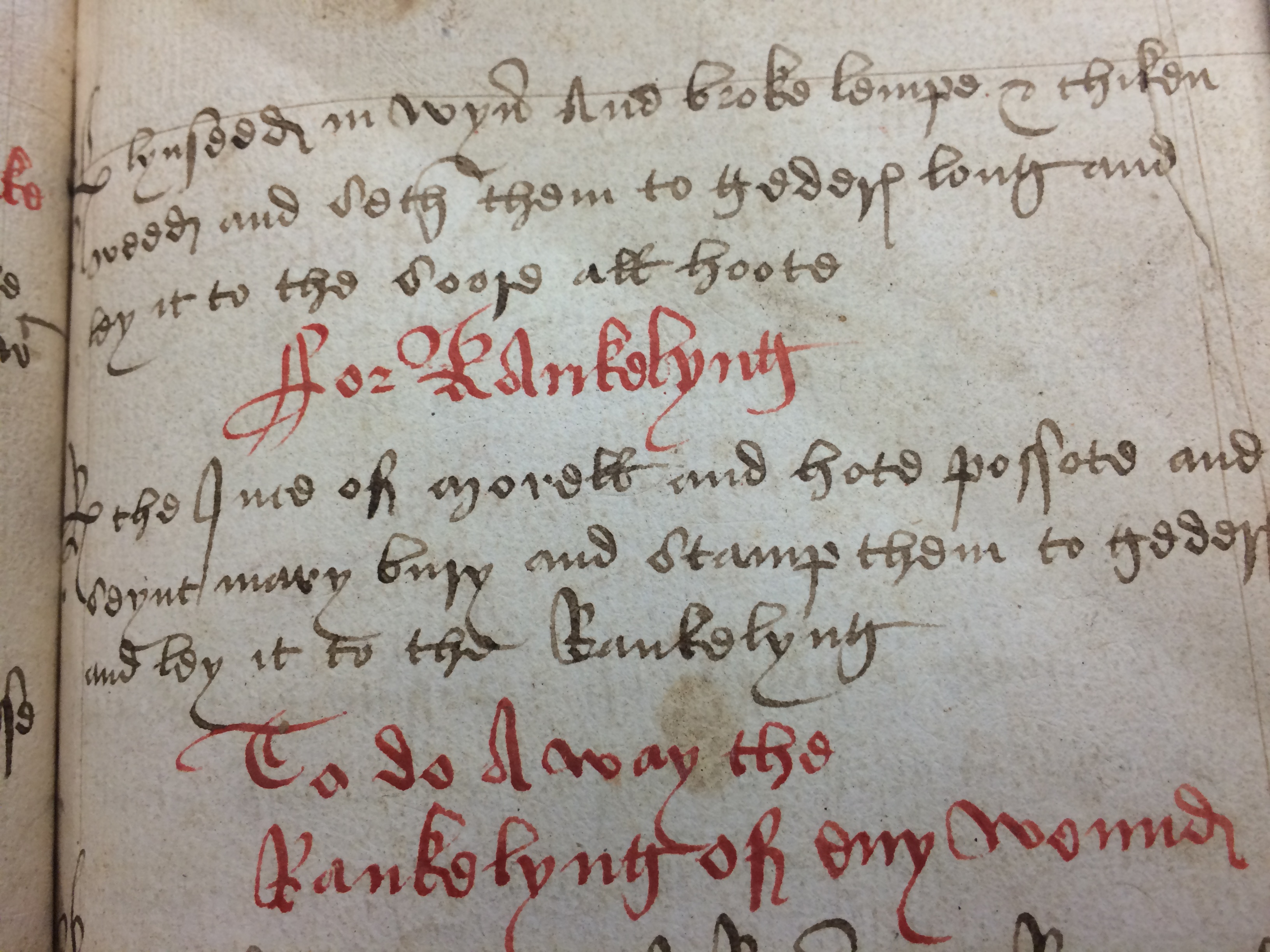

One of the most intriguing manuscripts of the Osler Library is Bibliotheca Osleriana 7591, a collection of Middle English medical recipes from the early sixteenth century. The recipes are from the Practica phisicalia composed by John of Burgundy (c. 1338–90), who was best known for his plague treatises. In his most famous tract, De epidemia, he identifies himself as ‘John with the beard’, practitioner of the art of medicine from Liège. As is typical of recipe collections of the period, John of Burgundy’s Practica covers treatments for the entire body, arranged from head to foot. The recipes treated everything from ‘the ffistula’ (p. 1) to ‘a charme for the tothake’ (p. 140).

The Osler copy of the Practica phisicalia is a relatively small and cheap production written in a fluid cursive script. It is likely that the manuscript, or perhaps the scribe, was from the northern part of England, as the text contains northern dialectical features. The codex survives in a good condition, although it has been rebound in a modern binding, and a few pages have been damaged.

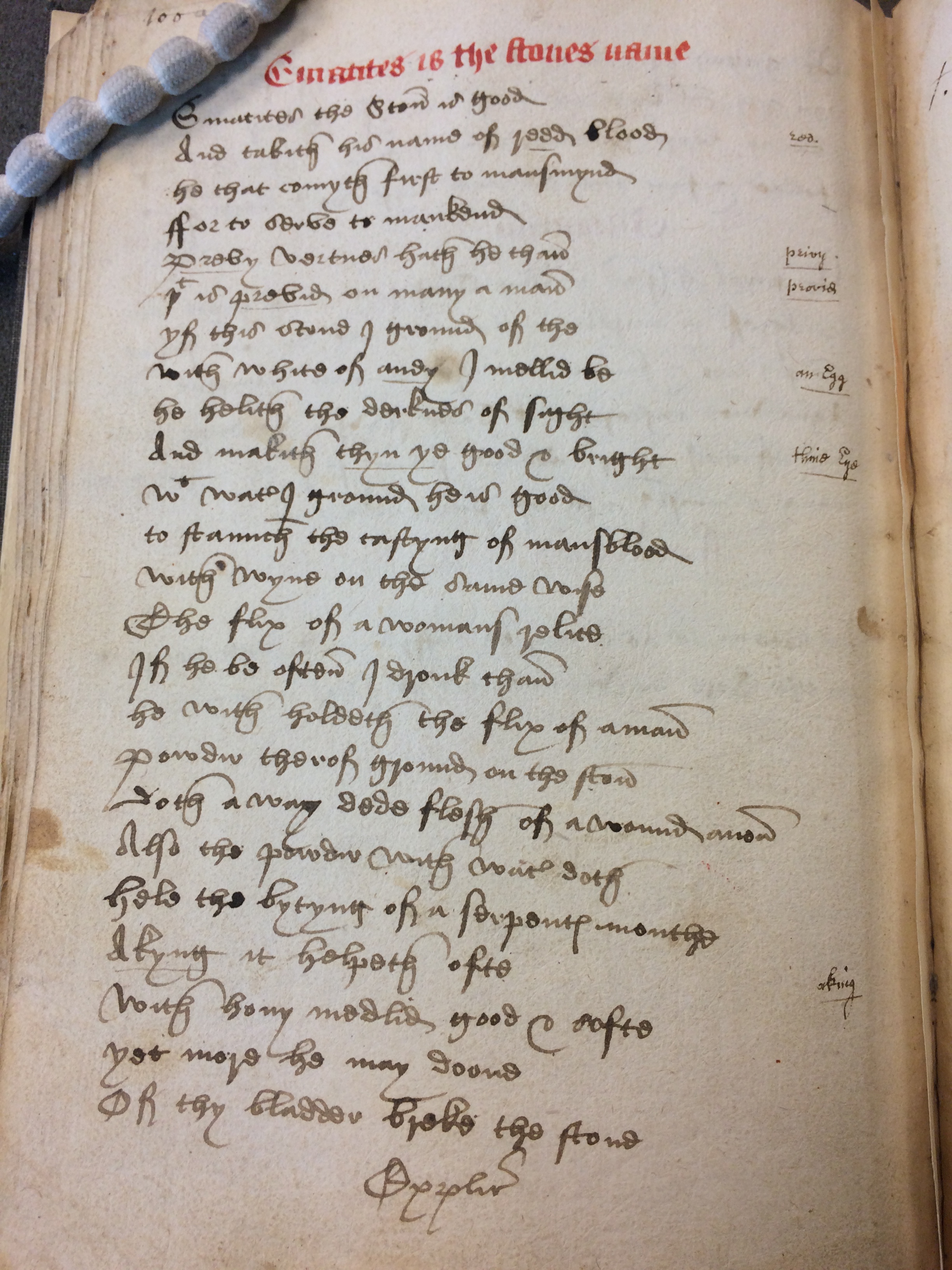

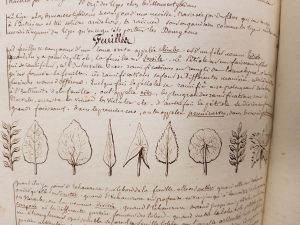

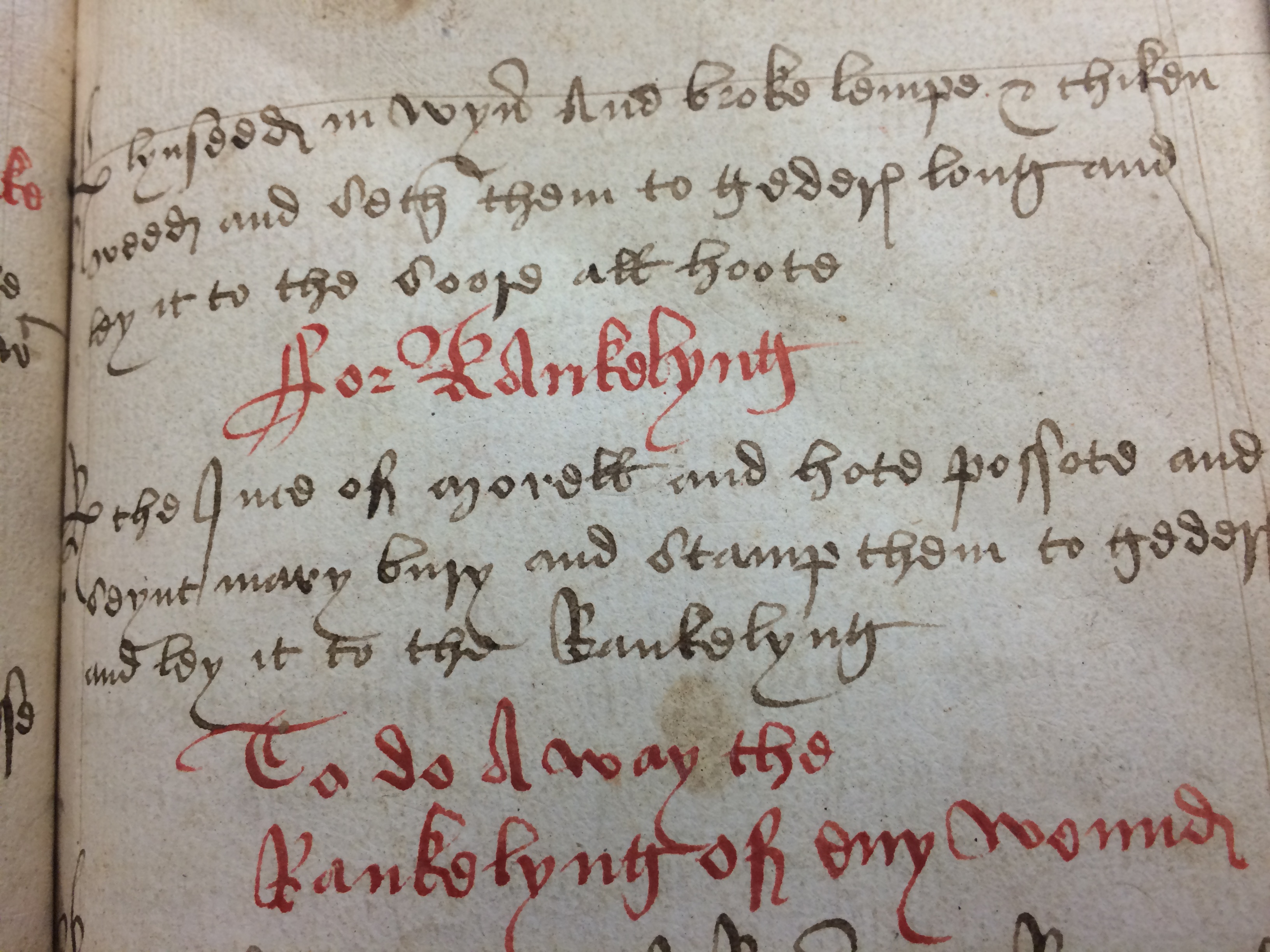

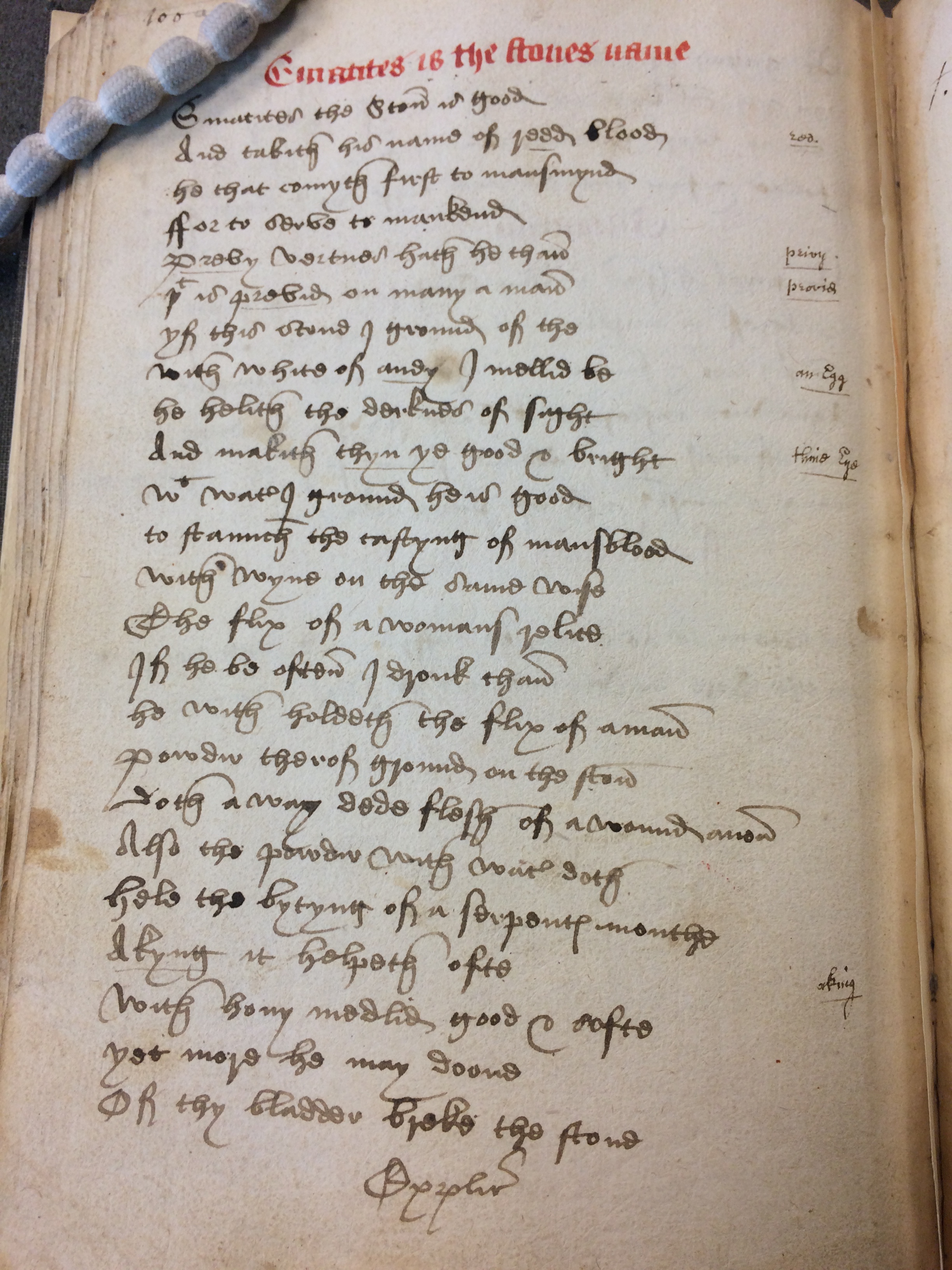

The codex does not only contain the Practica, as it also contains lists and lyrics on the practical uses of particular ingredients. On page 20 there is a list of the uses of ‘Wateris’ added by the hand of the main text into the bottom margin. This list comments, for example, that: ‘Water of calamynt is good for the stomake’ and ‘Water of violette is good to hele aman & for the peynes & for the lyver.’ Osler 7591 also contains a poem entitled ‘Ematites is the stones name’ (p. 100a) in 24 lines of iambic tetrameter.

These lyrics explain the uses of Hematite, a red iron ore. This page features an annotation hand that updates the spelling of certain words in the poem and provides comments. On the following page (p. 100b) the annotator explains that the lyrics are ‘a specimen of the poetry in those / Days; bring the virtues of the lapis / Hamatitis set forth in stylish verse.’ The fluid cursive secretary hand of the annotations match a signature at the beginning of the codex: ‘Ed. Cooper 1726.’ Cooper comments at other points throughout the manuscript, such as on page 61 where he explains that he owns a small octavo insert that he believes to have been composed by the same scribe.

These lyrics explain the uses of Hematite, a red iron ore. This page features an annotation hand that updates the spelling of certain words in the poem and provides comments. On the following page (p. 100b) the annotator explains that the lyrics are ‘a specimen of the poetry in those / Days; bring the virtues of the lapis / Hamatitis set forth in stylish verse.’ The fluid cursive secretary hand of the annotations match a signature at the beginning of the codex: ‘Ed. Cooper 1726.’ Cooper comments at other points throughout the manuscript, such as on page 61 where he explains that he owns a small octavo insert that he believes to have been composed by the same scribe.

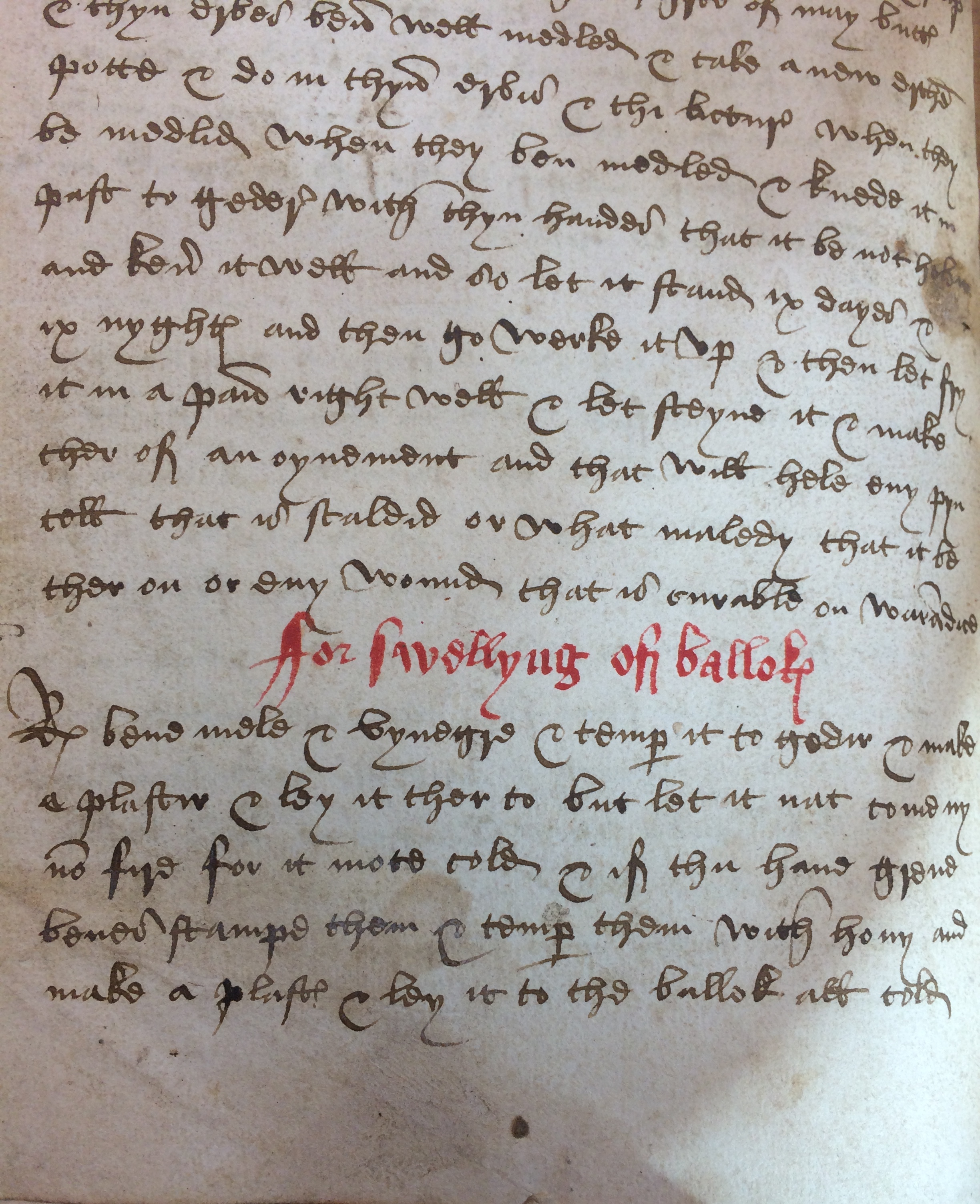

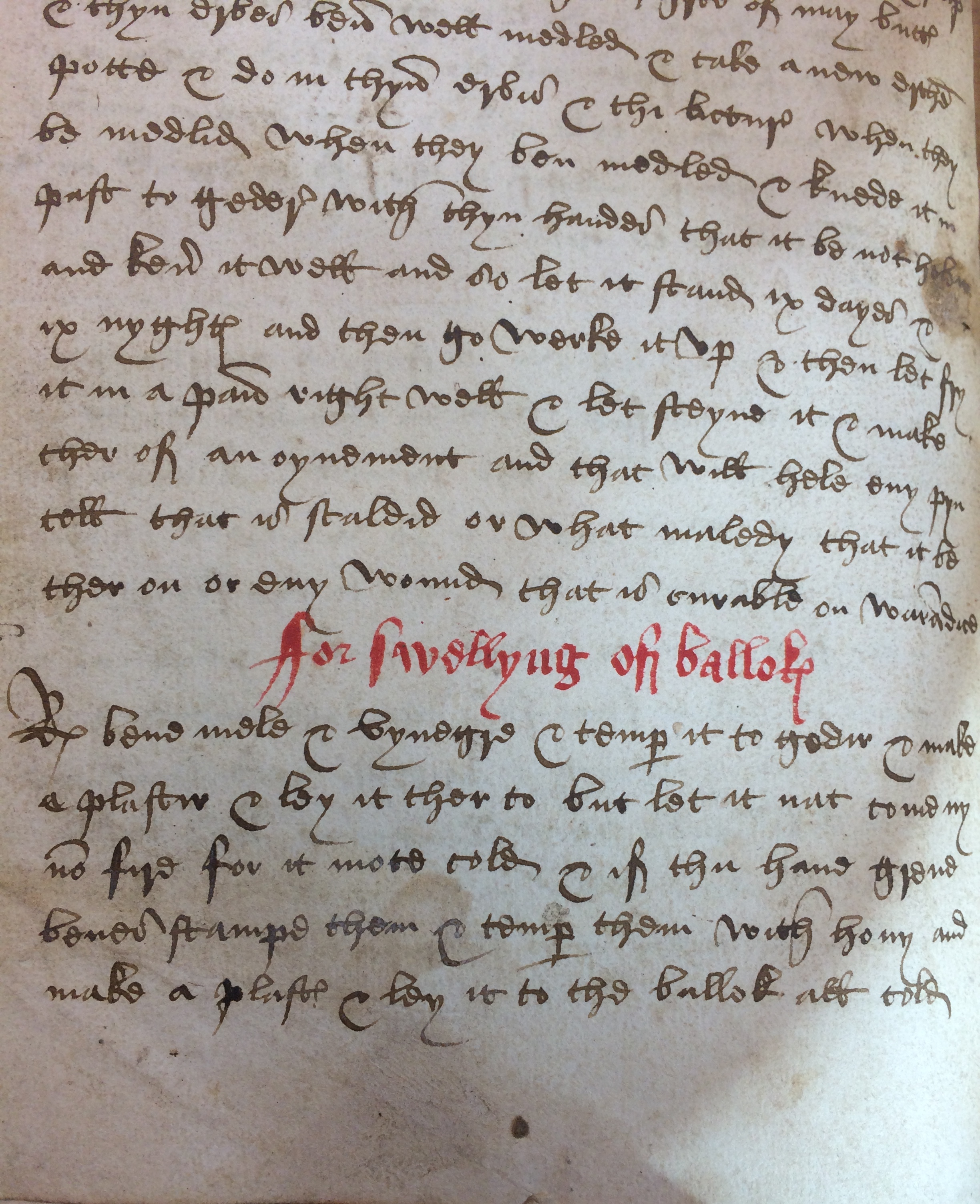

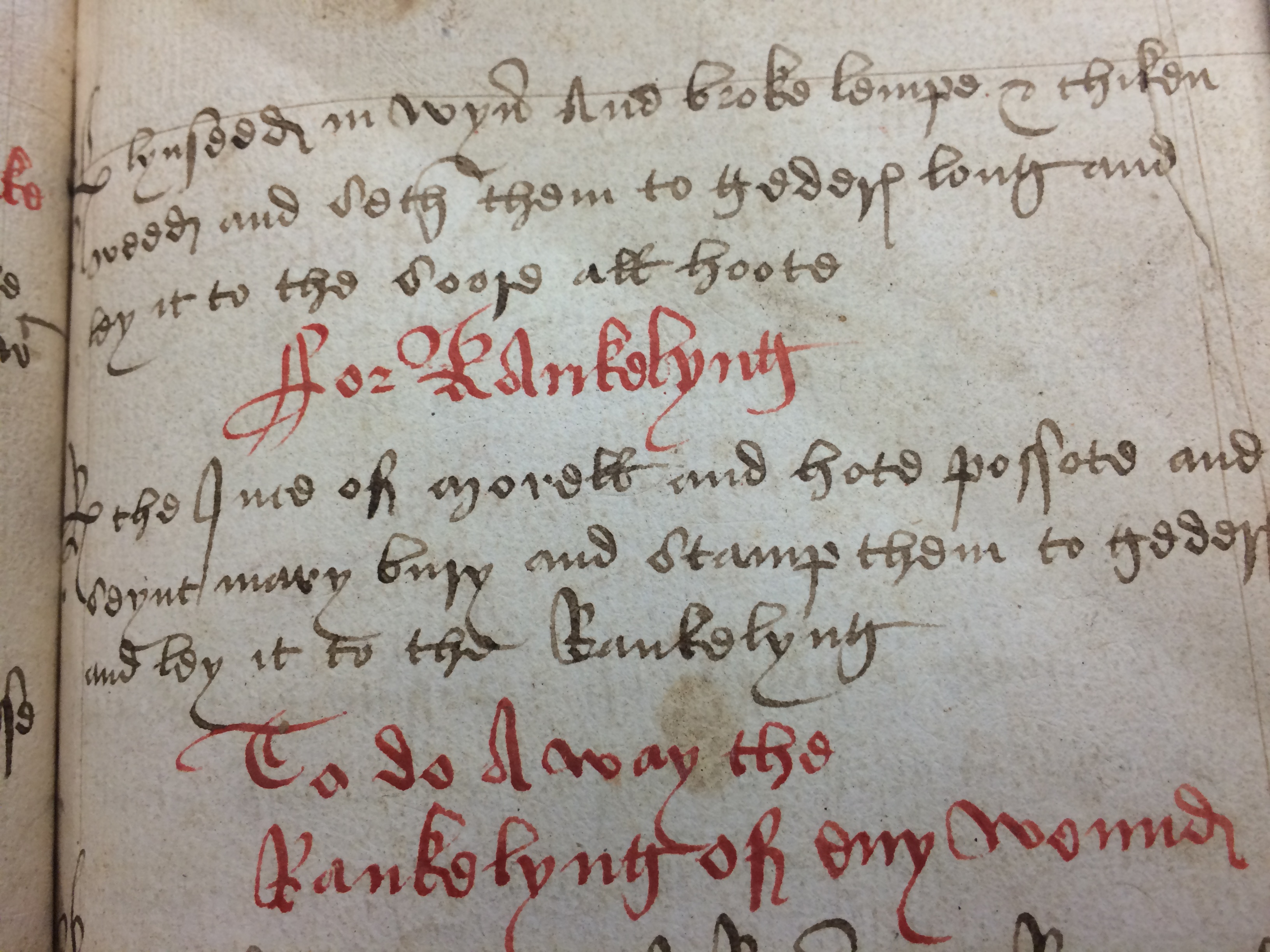

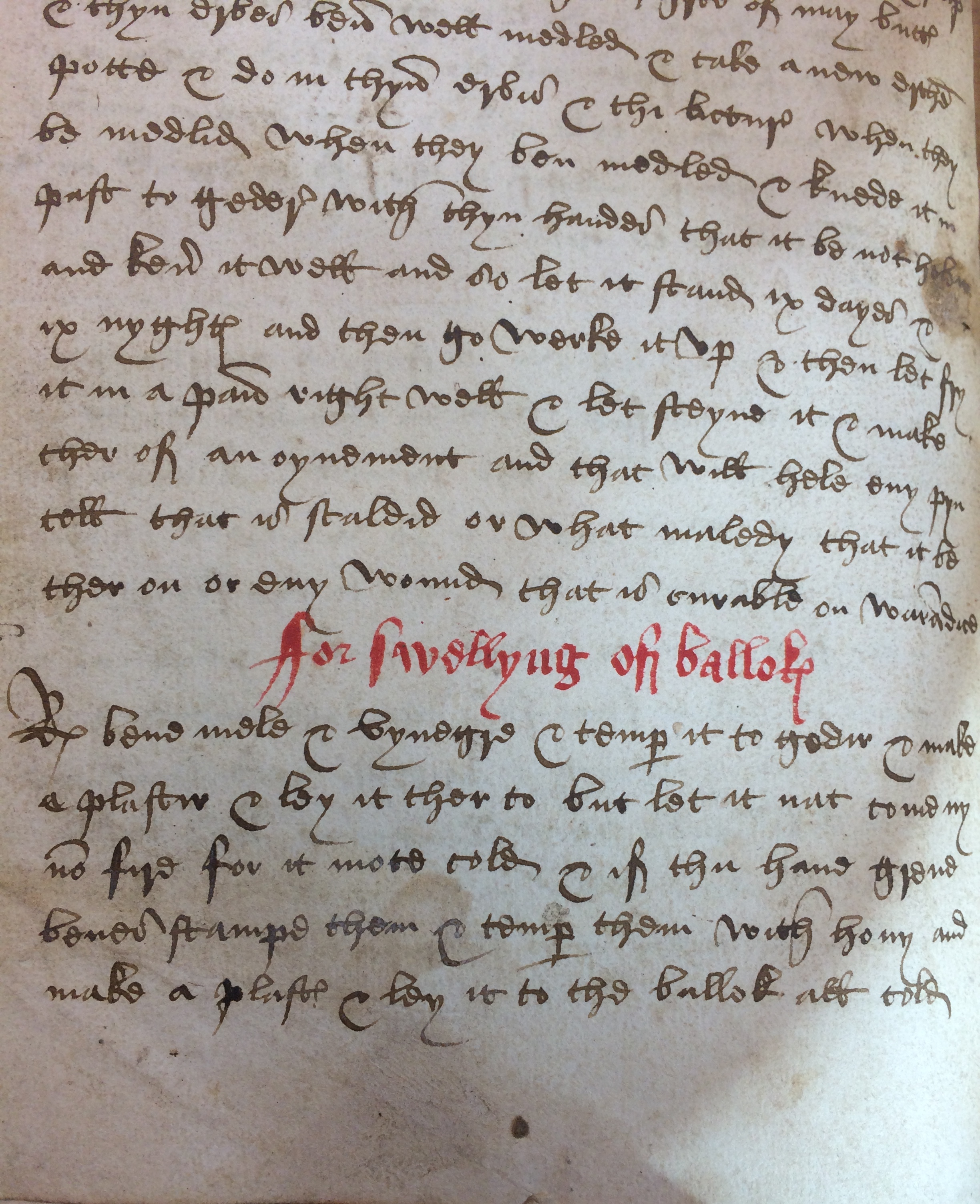

One of the most peculiar aspects of Osler 7591, is that its section on male genitalia has been excised from the manuscript. Two leaves are missing that contained almost all of the recipe ‘Ffor swellyng of ballokes’ (only the title and five lines survive) and the entirety of the recipe ‘Ffor ache in mannes lendes [loins or genitalia]’. We can be sure that two leaves are missing because the quire (gathering) in which these recipes are partially contained (quire six of ten) is the only quire of six in the entire manuscript (the rest of the quires are made up of eight leaves each). Also, remnants of the excised pages are visible, as the remaining stubs show clear signs of excision with clean lines that result from cutting.

Adding to this, the recipes concerning the penis and testicles that do survive in Osler 7591 are the only recipes in the entire manuscript that feature manicules (pointing hands) drawing attention to their titles. This suggests that they were at some point considered notable. Perhaps the two missing leaves were removed by a reader for ease of access in continued consultation. Equally, the leaves may have been excised as an act of censorship, because the owner of the manuscript did not appreciate the attention that they received.

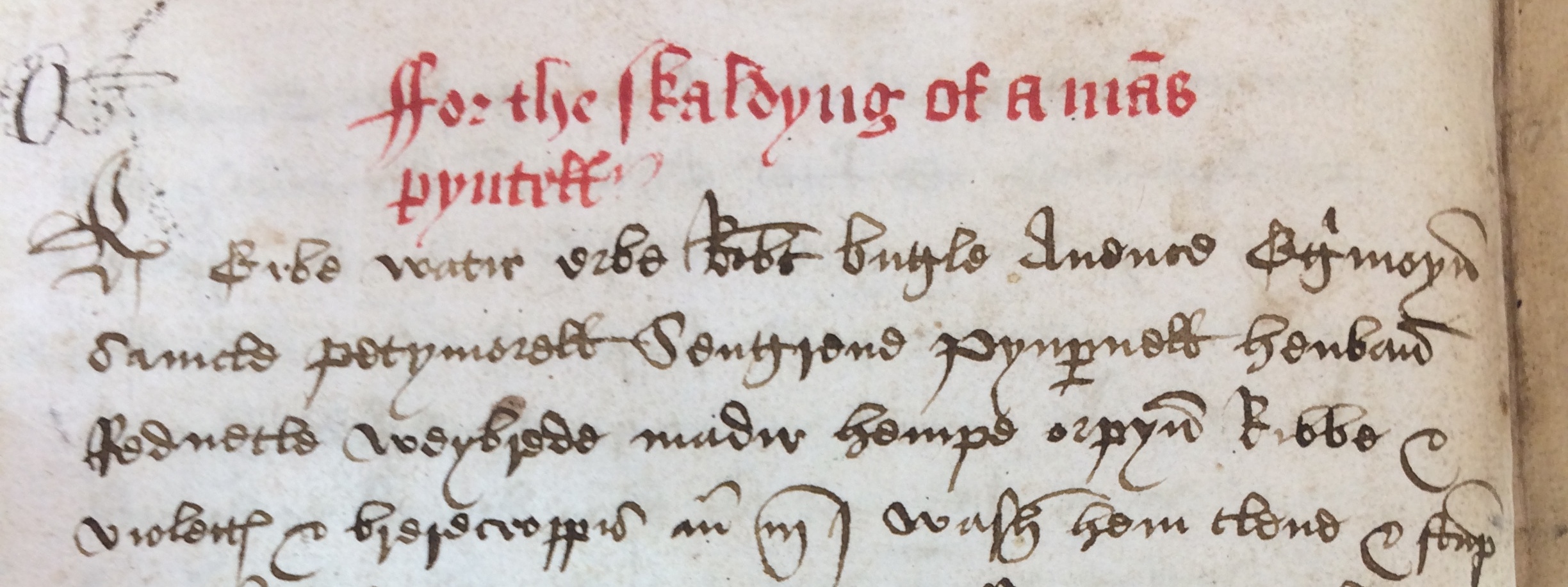

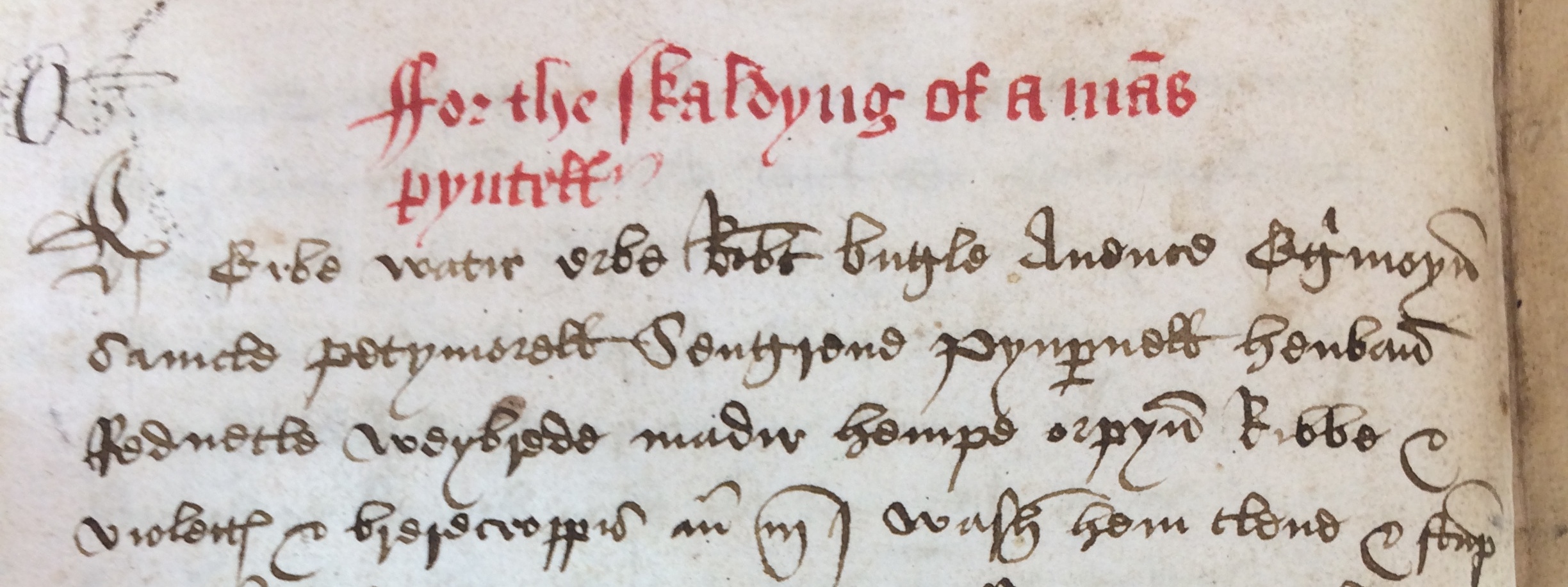

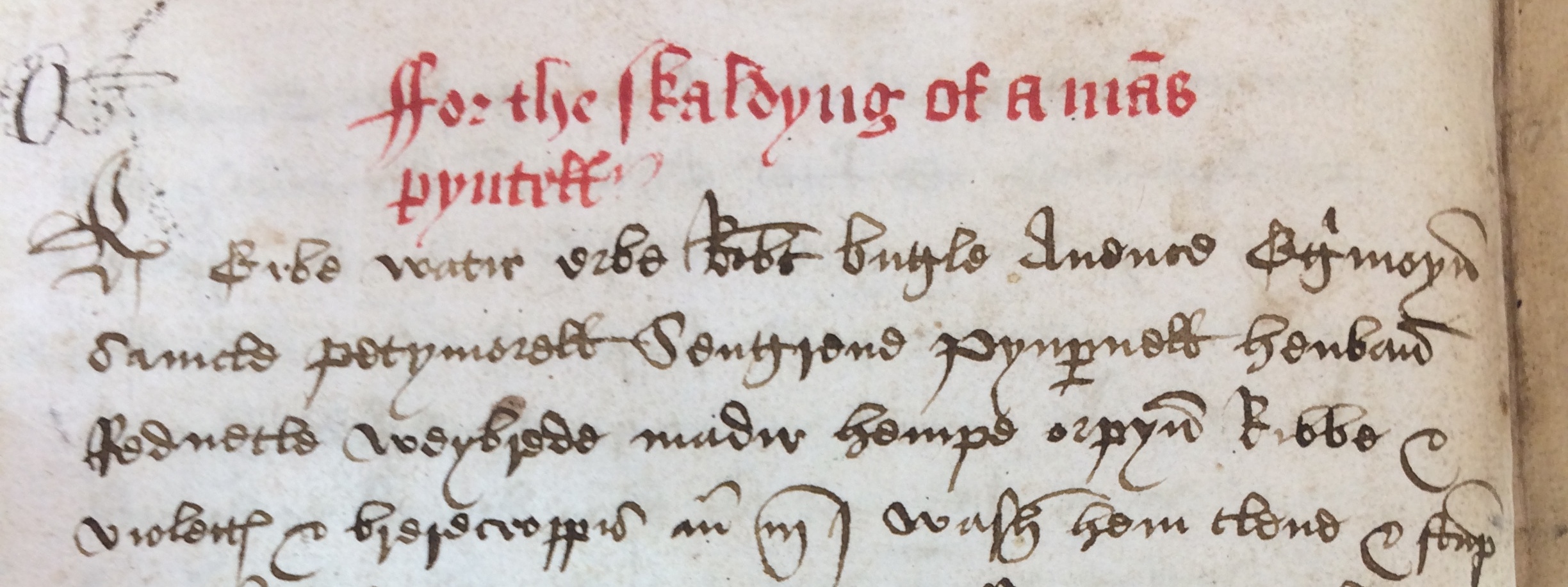

Osler 7591 shares an interesting parallel with London, Wellcome MS. 406, another copy of John of Burgundy`s Practica phisicalia. The same section of the text has been censored in this manuscript. Instead of removing pages, an annotator in Wellcome MS. 406 has crossed through offensive words in the titles of two recipes. The first case of censorship appears on folio 35 verso, in a recipe entitled: ‘For swellyng of a mannys veretrum’. The second censored recipe, on folio 36 recto, is entitled: ‘For scalding of a mannys veretrum’. In each title the Latin word ‘veretrum’ has been added by the annotator. This Latin replaces the Middle English term for penis, ‘pyntell’, which has been thoroughly crossed out in each case. One can only infer that the exchange of Middle English for Latin was done in the interest of taste, as the word ‘pyntell’ had vulgar, colloquial connotations that were not shared by ‘veretrum’. The censorship of Wellcome MS. 406 allowed readers educated in Latin to comprehend the treatments, but others would have been ignorant of what the recipes concerned.

The Osler and Wellcome manuscripts examined here reflect a trend in the early modern period where owners of medieval manuscripts became increasingly concerned with obscuring references to reproductive organs. Owners considered such content to be indecent and did not want readers to see the information. Whether through excising leaves or Latin glosses, the interventions in these manuscripts provide a clue as to how such codices were treated by post-medieval readers.

Excision de Moyen-Anglais Recettes Médicinales dans la bibliothèque Osler, Bibliotheca Osleriana 7591

L’un des manuscrits les plus intrigants de la bibliothèque Osler est Bibliotheca Osleriana 7591, une collection de recettes médicinales du Moyen-Anglais du début du XVIe siècle. Les recettes proviennent de la Practica phisicalia composée par Jean de Bourgogne (c. 1338-90), connue pour ses traités de peste. Dans son écriture le plus célèbre, De epidemia, il s’identifie comme « Jean avec la barbe », praticien de l’art de la médecine de Liège. Comme ç’est typique pour livres des recettes de la période, la Practica de Jean de Bourgogne couvre les traitements pour l’ensemble du corps, disposés de la tête aux pieds. Les recettes traitent tout de ‘the ffistula’ (p. 1) à ‘a charme for the tothake’ (p. 140).

La copie d’Osler de la Practica phisicalia est une production relativement petite et peu coûteuse, écrite dans un script cursive fluide. Il est probable que le manuscrit, ou peut-être le scribe, provenait du nord de l’Angleterre, car le texte contient des caractéristiques dialectiques du Nord. Le codex survit en bon état, bien qu’il ait été placé dans une liaison moderne, et quelques pages ont sont endommagées.

Le codex ne contient pas seulement le Practica, mais il contient également des listes et des paroles sur les utilisations pratiques d’ingrédients particuliers. À la page 20, il existe une liste des utilisations de ‘Wateris’ ajoutées par le scribe du texte principal dans la marge inférieure. Cette liste commente, par exemple, que: ‘Water of calamynt is good for the stomake’ et ‘Water of violette is good to hele aman & for the peynes & for the lyver.’ Osler 7591 contient également un poème intitulé ‘Ematites is the stones name’ (p. 100a) en 24 lignes de tétramètre iambique.

Ces paroles expliquent les utilisations de Hematite, un minerai de fer rouge. Cette page comporte une touche de notation qui met à jour l’orthographe de certains mots dans le poème et fournit des commentaires. Sur la page suivante (p. 100b), l’annotator explique que les paroles sont : ‘a specimen of the poetry in those / Days; bring the virtues of the lapis / Hamatitis set forth in stylish verse.’ Las écriture secrétaire fluide et cursive des annotations correspond à une signature au début du codex: ‘Ed. Cooper 1726.’ Il a commenté à d’autres points tout au long du manuscrit, comme à la page 61 où il explique qu’il possède un petit ‘octavo insert’ qu’il croit avoir été composé par le même scribe.

L’un des aspects les plus étranges d’Osler 7591 est que sa section sur les organes génitaux masculins a été retirée du manuscrit. Il manque deux feuilles qui contiennent presque toute la recette : ‘Ffor swellyng of ballokes’ (seulement le titre et cinq lignes restent) et la totalité de la recette : ‘Ffor ache in mannes lendes [longes ou organes génitaux]’. Nous pouvons être sûrs que ces deux feuilles sont manquantes parce que le quire dans lequel ces recettes sont partiellement contenues (quire six de dix) est le seul nombre de six dans le manuscrit entier. En outre, les restes des pages excisées sont visibles, car les bouts restants montrent des signes clairs d’excision avec des lignes propres résultant de la coupe.

En ajoutant à cela, les recettes concernant le pénis et les testicules qui survivent à Osler 7591 sont les seules recettes dans le manuscrit entier qui présentent des manicules (les mains que point) qu’attirent l’attention sur leurs titres. Cela suggère qu’ils étaient à un moment donné considérés comme notables. Peut-être que les deux feuilles manquantes ont été retirées par un lecteur pour faciliter l’accès en consultation continue. De même, les feuilles peuvent avoir été excisées comme un acte de censure, parce que le propriétaire du manuscrit n’a pas apprécié l’attention qu’ils ont reçue.

Osler 7591 partage un parallèle intéressant avec Londres, Wellcome Ms. 406, une autre copie de La Practica phisicalia de Jean de Bourgogne. La même section du texte a été censurée dans ce manuscrit. Au lieu de supprimer des pages, un annotateur dans Wellcome MS. 406 a tracé une ligne à travers des mots offensifs dans les titres de deux recettes. Le premier cas de censure apparaît sur le folio 35 verso, dans une recette intitulée: ‘For swellyng of a mannys veretrum’. La deuxième recette censurée, sur le folio 36 recto, est intitulée: ‘For scalding of a mannys veretrum’. Dans chaque titre, le mot Latin ‘veretrum’ a été ajouté par l’annotateur. Ce mot Latin remplace le Moyen-Anglais terme pour le pénis, ‘pyntell’, qui a été complètement éliminé dans chaque cas. On peut déduire que l’échange de l’Moyen-Anglais pour le Latin a été fait dans l’intérêt du goût, car le mot « pyntell » avait des connotations vulgaires qui n’étaient pas partagées par « veretrum ». La censure de Wellcome MS. 406 a permis aux lecteurs du livre, éduqués en latin de comprendre les traitements, mais d’autres auraient ignorant de quoi les recettes concernées.

Les manuscrits Osler et Wellcome ont examiné ici sont représentatif d’un trend dans le début de l’époque moderne, où les propriétaires des manuscrits médiévaux étaient de plus en plus préoccupés par des obscurcir références aux organes reproducteurs. Les propriétaires considéraient que ce contenu était indécent et ne voulait pas que les lecteurs puissent voir l’information. Que ce soit par les excisions, ou les gloses Latin, les interventions dans ces manuscrits fournissent un indice quant à la façon dont ils ont été lus.

These lyrics explain the uses of Hematite, a red iron ore. This page features an annotation hand that updates the spelling of certain words in the poem and provides comments. On the following page (p. 100b) the annotator explains that the lyrics are ‘a specimen of the poetry in those / Days; bring the virtues of the lapis / Hamatitis set forth in stylish verse.’ The fluid cursive secretary hand of the annotations match a signature at the beginning of the codex: ‘Ed. Cooper 1726.’ Cooper comments at other points throughout the manuscript, such as on page 61 where he explains that he owns a small octavo insert that he believes to have been composed by the same scribe.

These lyrics explain the uses of Hematite, a red iron ore. This page features an annotation hand that updates the spelling of certain words in the poem and provides comments. On the following page (p. 100b) the annotator explains that the lyrics are ‘a specimen of the poetry in those / Days; bring the virtues of the lapis / Hamatitis set forth in stylish verse.’ The fluid cursive secretary hand of the annotations match a signature at the beginning of the codex: ‘Ed. Cooper 1726.’ Cooper comments at other points throughout the manuscript, such as on page 61 where he explains that he owns a small octavo insert that he believes to have been composed by the same scribe.