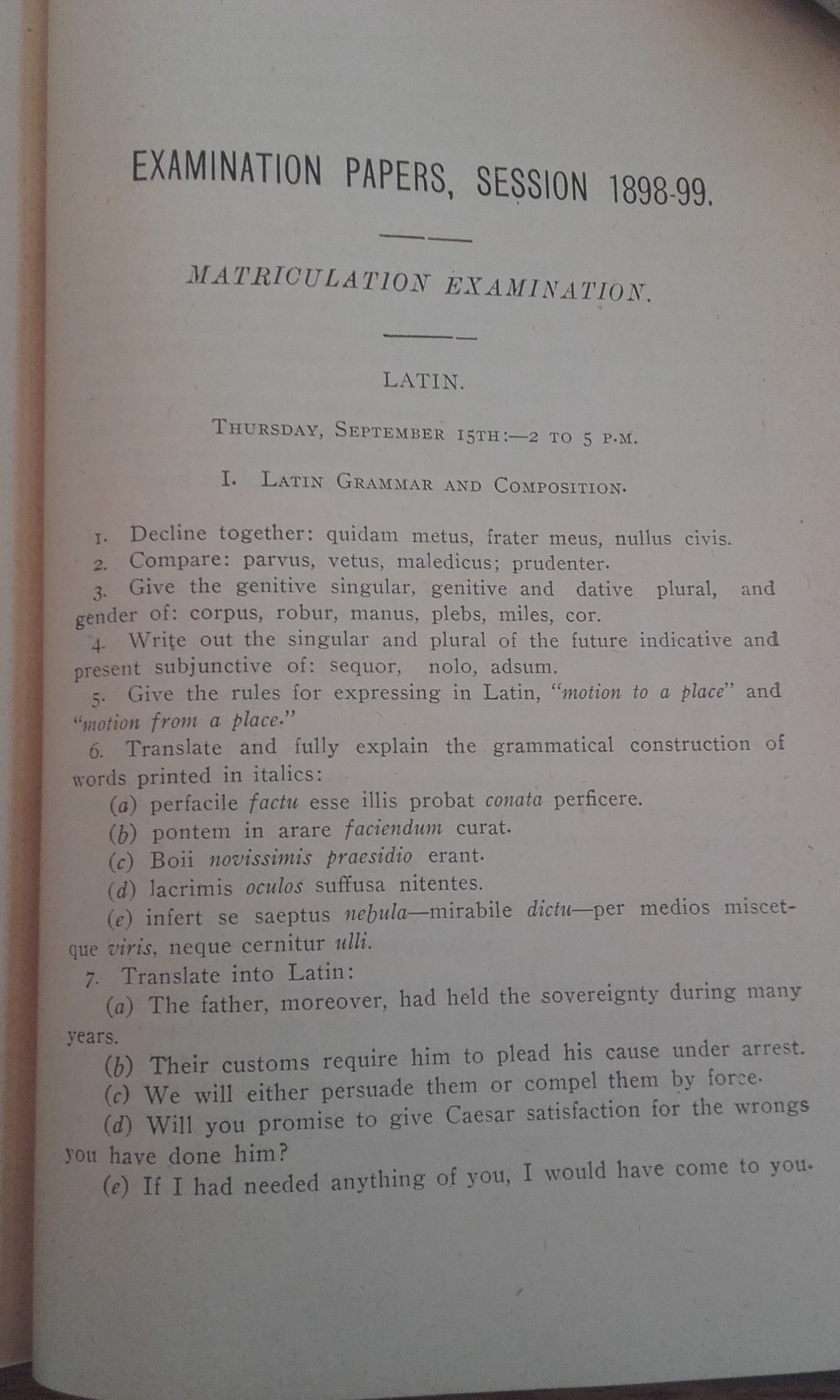

By Mary Yearl, Head Librarian, Osler Library of the History of Medicine

After spending the first few months of its new Montréal life in careful hands in the Redpath Library Building for cataloguing and, later, digitization, Eugène Ducrot’s manuscript notebook on natural history has finally arrived at its permanent home: the Osler Library of the History of Medicine.

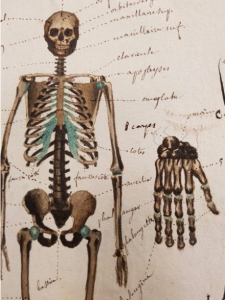

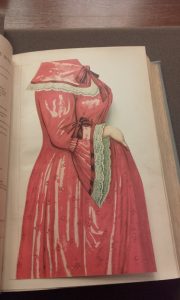

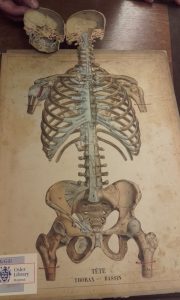

Note the fine use of colour in Ducrot’s skeleton. Page 44 in Cahier d’histoire naturelle (1835-1837) : à Moulins

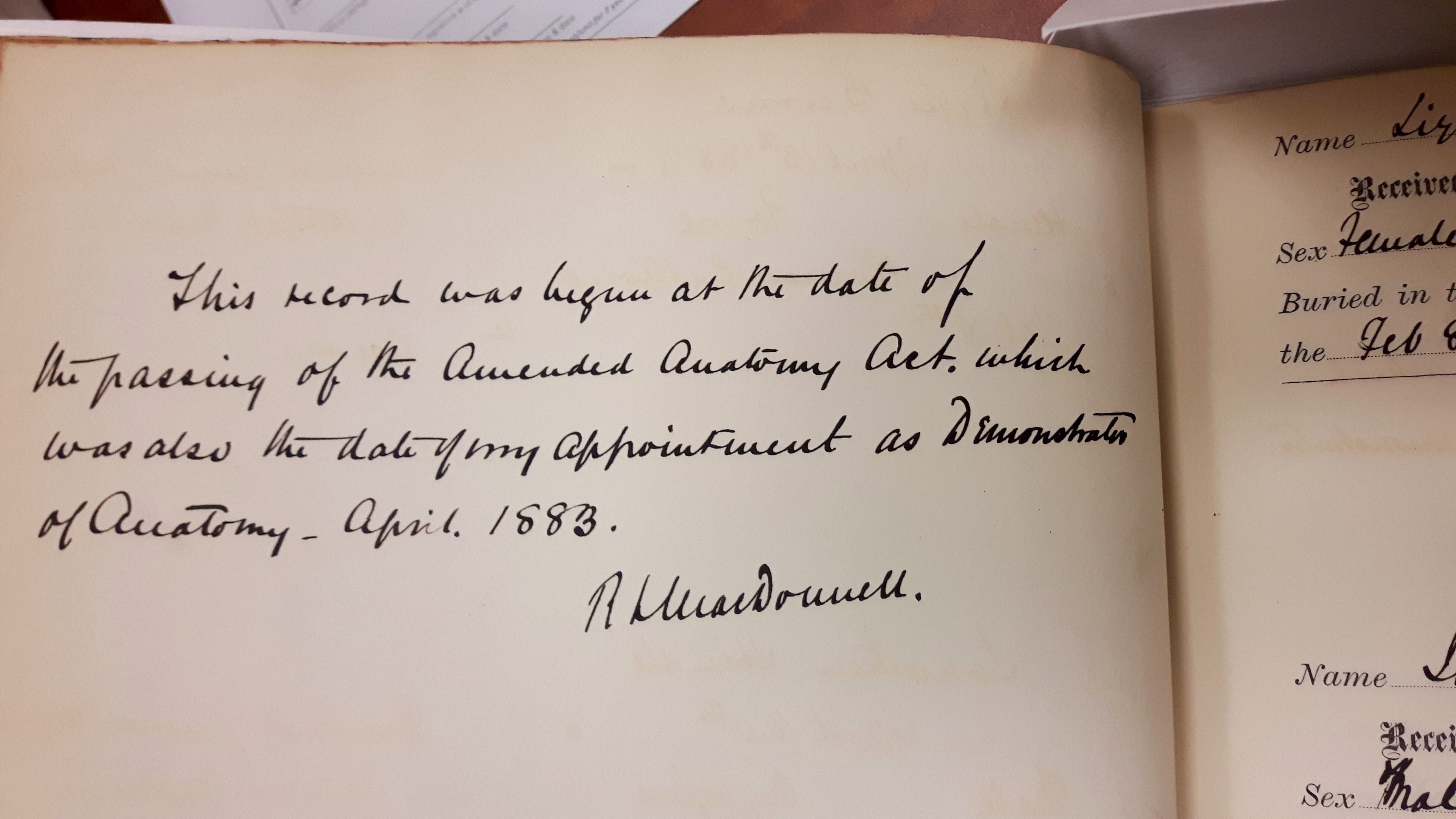

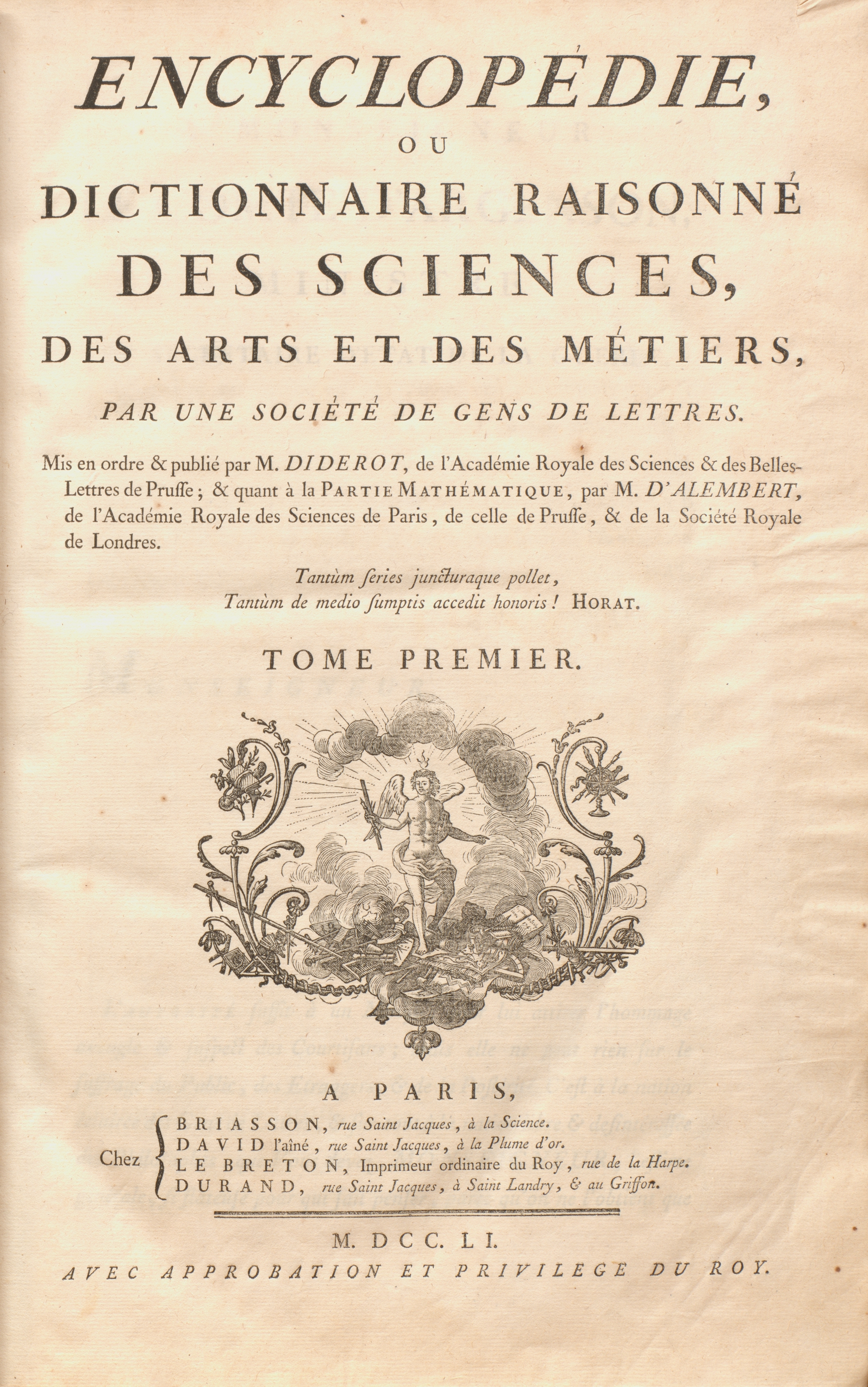

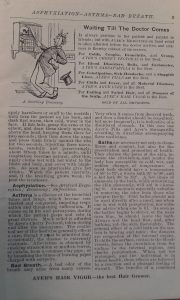

The title page provides a satisfying amount of information to the reader, though it offers barely a glimpse of the beauty that lies within. In the upper left-hand corner in petite pencil script, it is noted that the manuscript was written by J.E. Ducrot, after the lectures of Mr. Denou in Moulins. In bolder ink script, a 19th-century hand announces “Cahier d’histoire naturelle (1835-1837) à Moulins, à Eugène Ducrot.” Finally, nearer to the bottom, one learns that the manuscript was given to a Mr. Chavignaud, Moulins, 1848.

If the first manuscript page betrays a certain attention to detail, this is continued in the table of contents. The subjects covered include physiology (lessons 1-10), descriptive zoology (“méthode de M.G. Cuvier” – lessons 11-47), botany (lessons 48-53), and geology (lessons 54-56). To provide some sense of the deliberation given to each of the 56 lessons described, consider the 9th lesson, “Sens de la vue – Lumière – appareil de la vision – sourcils – soupière – appareil lacrymal – muscles de l’oeil – situation de l’oeil – usage des différentes parties de l’oeil – Voie.” This level of detail, and sometimes more, is present for nearly every entry in the contents and suggests that this manuscript would serve as a worthy source for those interested in studying natural history education in France during the July Monarchy specifically, or in the 19th century generally.

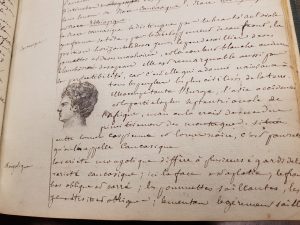

The majority of the manuscript is devoted to zoology and might be considered fairly timeless, at least with respect to the specific topics of natural history studied. However, some portions reveal the thinking of a past era. For instance, there is a relatively short section on the human races, which Ducrot records as Caucasian, Mongolian, and Ethiopian. When Denou was lecturing, ethnographic and anthropological studies had not yet been confirmed as academic disciplines, though the 1839 foundation of the Société Ethnologique de Paris came shortly after the end date of Ducrot’s notes.

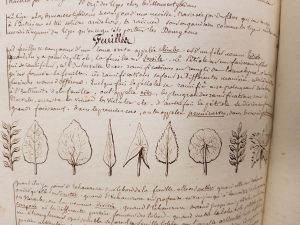

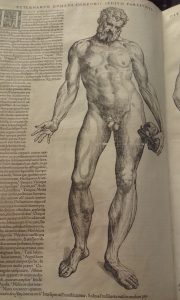

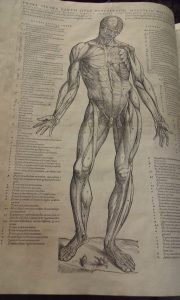

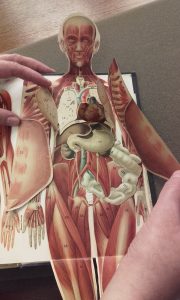

Without question, what called attention to the manuscript to begin with were the images. Interestingly, Ducrot’s section on botany is remarkably devoid of illustrations; only on one page in the (admittedly fairly limited) section are there drawings, and they demonstrate the shapes of leaves but do not contain written identification. Whether this represents a lack of interest or not would be difficult to say without further examination; there are, however, more illustrations in the similarly brief section on geology than there are on botany.

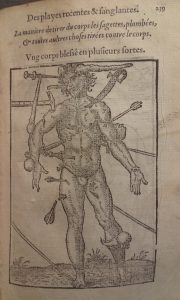

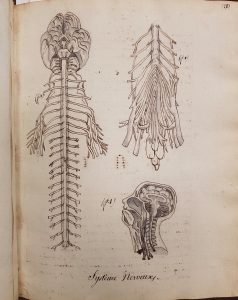

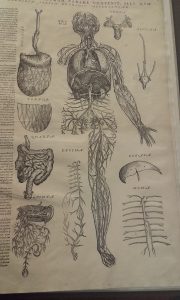

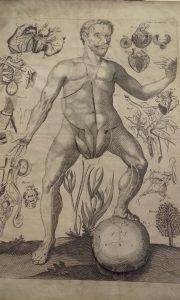

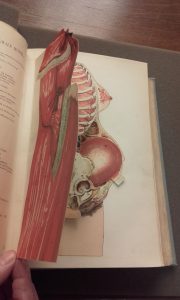

The true focus of the drawings, like that of the manuscript, is on zoology. In that realm, Ducrot’s detail is impressive. He lists the bones, used watercolour to display the heart and lungs (including an attempt to recreate some detail of the inside of the heart), provides an ink drawing of the nervous system, and describes the structure of teeth in a series of small figures.

Eugène Ducrot’s Cahier d’histoire naturelle is a new acquisition that has relevance to visitors whose interests lie in diverse interests. The drawings themselves are admirable; the course of study followed by Ducrot might well be useful to those studying pedagogy in France in the mid-nineteenth century; and historians of medicine and science will appreciate the detail afforded by Ducrot to his subject matter. Regardless of the audience, the manuscript is visually impressive and we are pleased that it has found a home at the Osler Library.

Using watercolour to reveal the heart and lungs. Page 9 in Cahier d’histoire naturelle (1835-1837) : à Moulins

Read the full volume in the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/McGillLibrary-osl_cahier-dhistoire-naturelle_QH51D831837-18271 part of our over 250 titles from the Osler Library that have been digitized and made available to everyone.

![[Calendar for Austria, 1496], Osler room, folio WZ 230 C149 1495](https://blogs.library.mcgill.ca/osler-library/files/2017/04/20170406_114850-300x180.jpg)