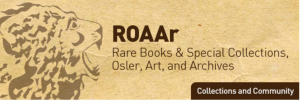

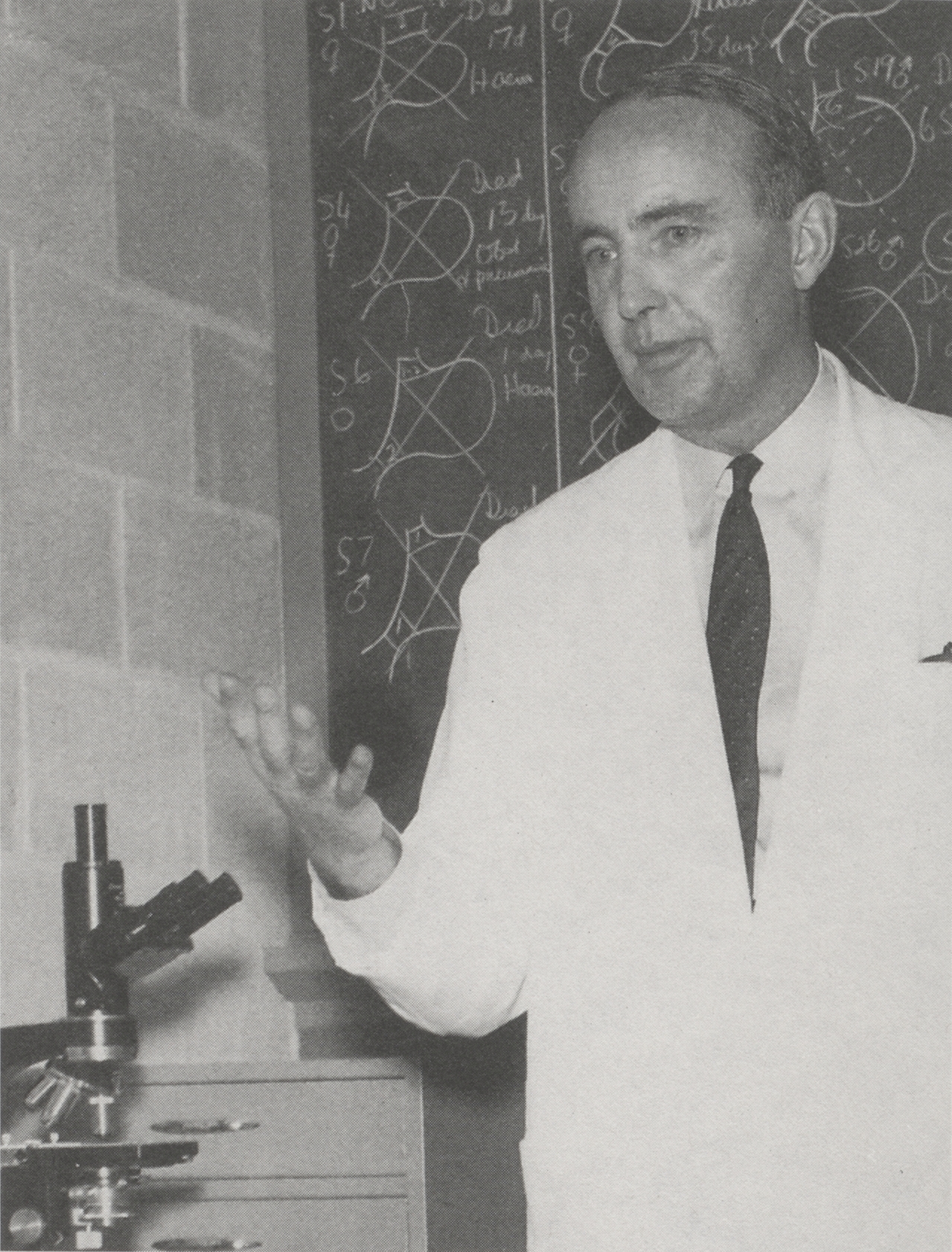

H. Rocke Robertson at the Montreal General Hospital, 1960. McGill University Archives, photographic collection, PU044121.

H. Rocke Robertson was a distinguished surgeon and the first McGill graduate to become Principal and Vice Chancellor of McGill University. An enthusiastic supporter of the Osler Library, Dr. Robertson was an instrumental force behind the Osler Library’s move from the Strathcona Building to its current location in the McIntyre Medical Building in the 1960s.

In 1972, he organized the Friends of the Osler Library whose financial support allows the Library to continue to buy material, preserve its rich collection, and make it available to others. After the opening of the Francis Wing in 1978, a rare books room was named in Dr. Robertson’s honour; since the Library’s most recent reconfiguration, the entire area surrounding the Osler Room is now named in his honour, containing the Library’s manuscripts, archival materials, and post-1840 rare materials, all of which are identified with the location code “Osler – Robertson” in the online catalogue.

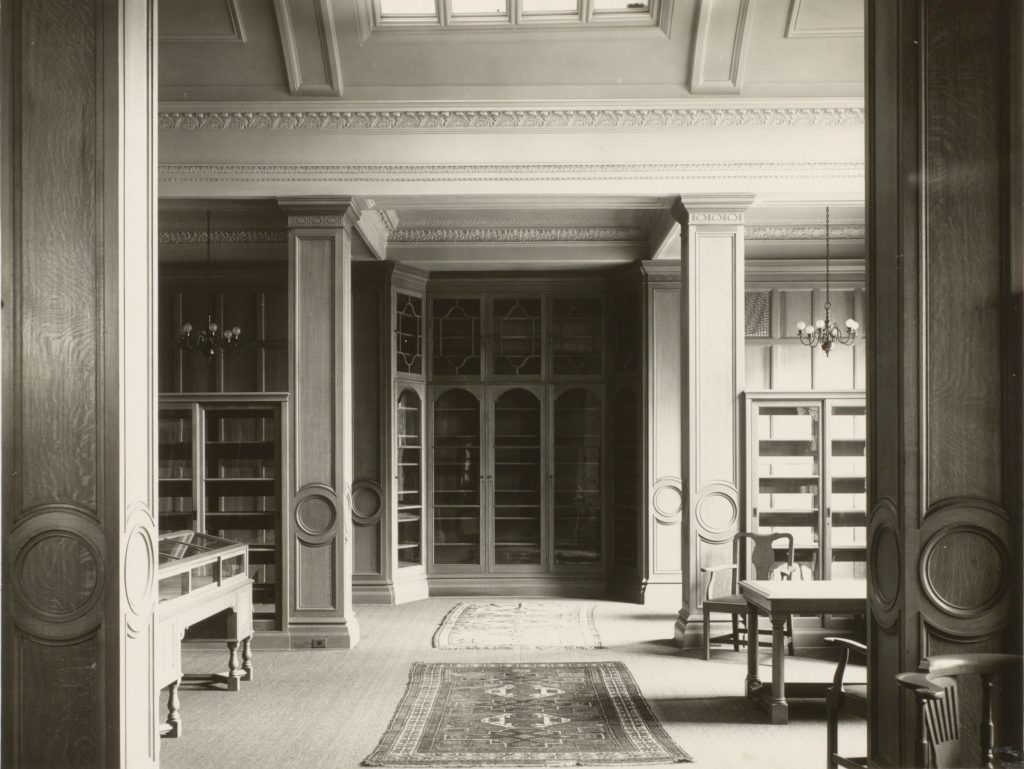

The H. Rocke Robertson Room at the Osler Library.

Thanks to Dr. Robertson’s initiative, his graduating class in Medicine of 1936 presented a generous endowment fund to the Osler Library as their 50th anniversary gift, which now pays for most of the Library’s new acquisitions of rare books, and finances the Osler Library Fellowships. As Prof. Faith Wallis wrote in her reminiscence of Dr. Robertson: “In this way, Medicine ’36 made possible for the 21st century what Osler’s bequest made possible for the 20th: the acquisition of new resources for the history of medicine, and the provision of means for their scholarly use.” (Wallis 1998: 2)

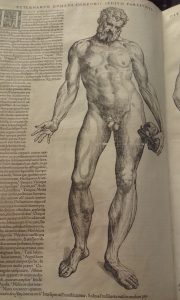

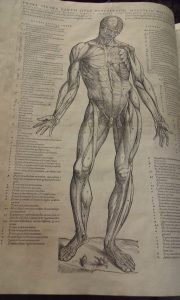

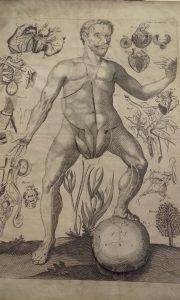

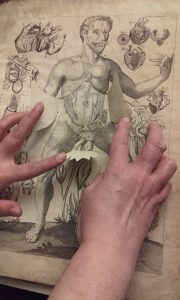

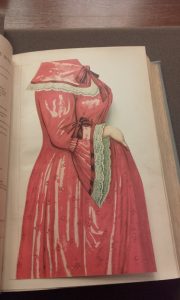

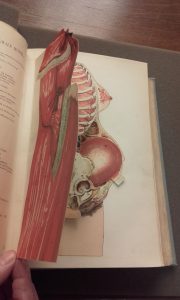

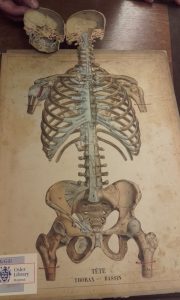

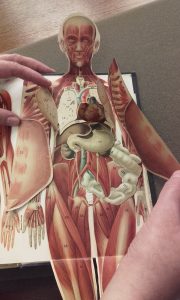

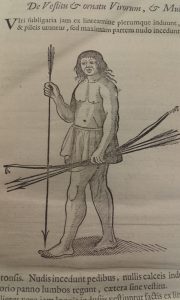

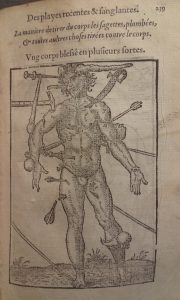

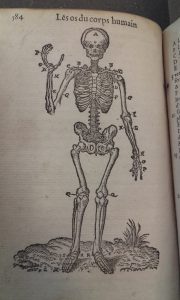

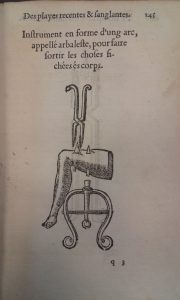

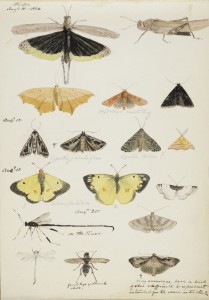

Illustration from Lorenz Heister: Institutions de chirurgie […]. Paris: P. Fr. Didot le jeune, 1771.

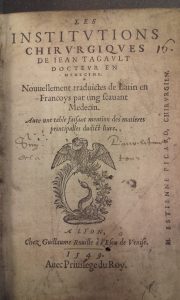

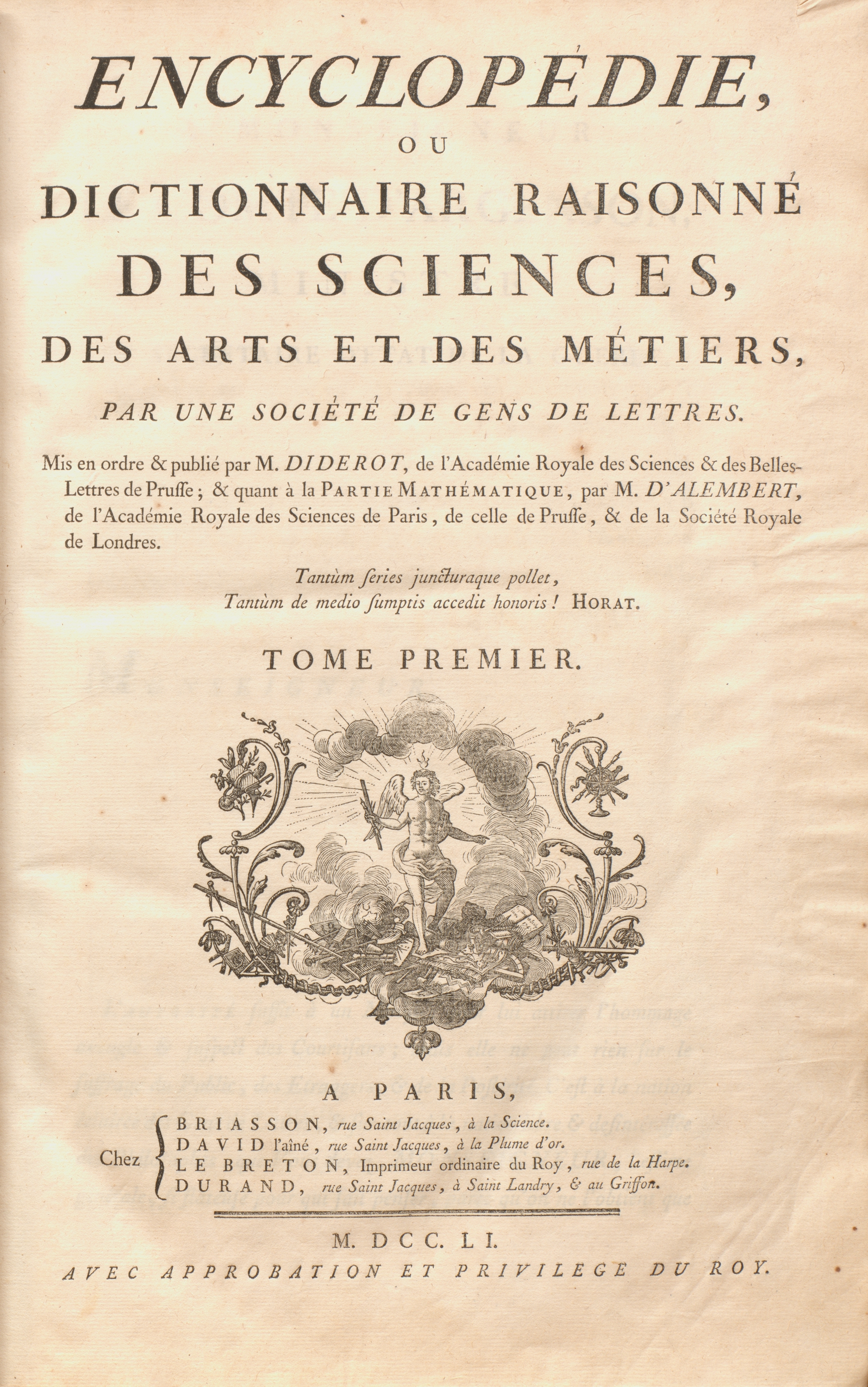

Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une Société de gens de lettres. Mis en ordre & publié par M. Diderot […] & quant à la partie mathématique par M. D’Alembert […]. Paris: Briasson [et al.], 1751. Title Page of the first volume.

“Gift of: H. Rocke Robertson” on the front endpapers of the first volume of the Encyclopédie.

Several rare books from H. Rocke Robertson’s collection can also be found at McGill’s Rare Books & Special Collections, including rare editions of works by John Dryden, Oliver Goldsmith, and Samuel Johnson, as well as the 1686 edition of Thomas Browne’s collected works, whose Religio Medici was William Osler’s favourite book.

The H. Rocke Robertson Fonds are held at the McGill University Archives.

H. Rocke Robertson died 20 years ago on February 8, 1998.

Bibliography:

Lough, John. Essays on the Encyclopédie of Diderot and D’Alembert. London: Oxford University Press, 1968. [Osler Library AE 1 L887es 1968]

Pound, Richard W. Rocke Robertson: Surgeon and Shepherd of Change. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2008. [eBook] [Osler Library WZ 100 R6493p 2008]

Roberton, H. Rocke. “W.O. and the O.E.D.” Osler Library Newsletter 88 (October 1991): 1-3. [PDF]

Wallis, Faith. “The Encyclopédie in the Osler Library.” Osler Library Newsletter 62 (October 1989): 1-2. [PDF]

Wallis, Faith. “H. Rocke Robertson: A Personal Reminiscence.” Osler Library Newsletter 88 (June 1998): 1-2. [PDF]