Guest post by Annelise Dowd. Annelise is a McGill University Master of Information Studies student with research interests in the digital humanities, library accessibility, and special collections outreach.

“He told us there were two subjects, and that as you were nervous he’d set you and Jim to work first; that our turn would come. He pointed to a grave; said that’s where would have to work; told us not to begin until he returned, as we might be caught; and that when we heard the whistle we were to run to the gate.”

“My Last Experience of Resurrectionning,”

McGill University Gazette,vol. 1, no. 4: January 1, 1874

The Origins of McGill Student Body-Snatching

In the 1830s, the nascent McGill Medical Faculty was incorporating the practice of dissection as the central method for anatomical instruction. However, even with the introduction of the Anatomy Act in 1843, an act intended to legally require institutions to supply bodies to medical faculties, the city of Montréal failed to donate an adequate number of cadavers. With limited options and little institutionally provided dissection material, McGill medical students quite literally took the issue into their own hands.

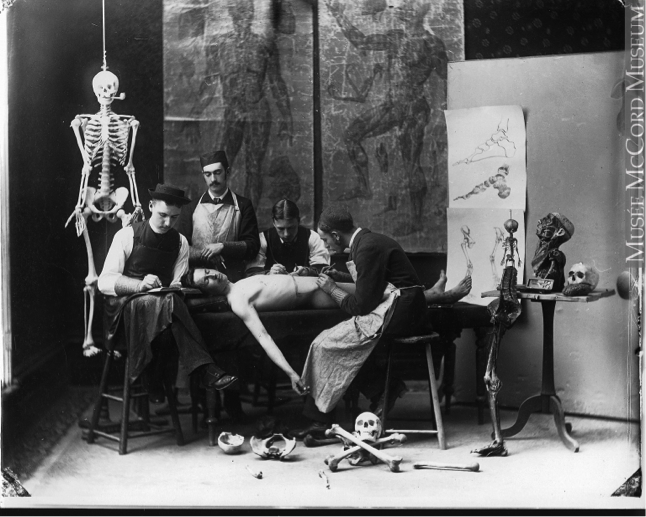

Portrait of the McGill “Resurrectionists”

The McGill University Gazette, McGill’s first newspaper, illustrates the figure of the student body-snatcher, or a more popular term at the time, “resurrectionist.” Medical students resurrected corpses for one of two purposes: for their own anatomical exams, or to supply bodies to their professors, with a reward of $30-$50 per body. For a number of medical students, body-snatching was an efficient, albeit morbid, means to cover one’s tuition.

Body-snatching was often a winter activity, due to the frozen ground preventing the burial of bodies. Until the ground thawed, corpses were stored above ground in cemetery “dead houses,” an easy target for students to forcibly enter and steal bodies. A winter body-snatching trip would typically include hiking to Côte-des-Neiges or Mount Royal cemetery in the dead of night, removing the corpses from their caskets, and tobogganing down the snow-covered slope with their “subjects” in tow.

The legal ramifications for body snatching were minor, and the general attitude towards body-snatching amongst the medical student body was openly positive. In fact, students fined in court for body snatching in 1875 were hoisted on the shoulders of a sea of medical students, chanting and singing in encouragement of their classmates’ deeds!

The Continued Legacy of Body-Snatching

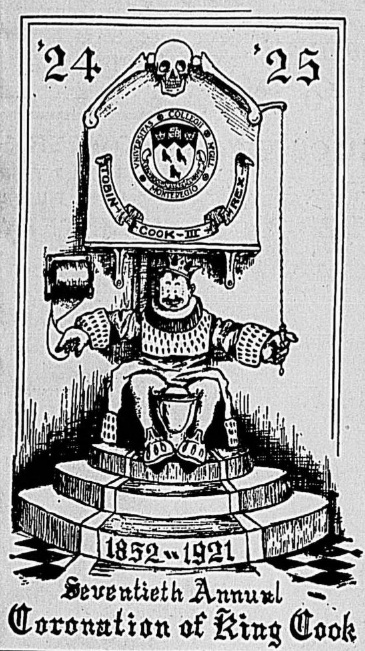

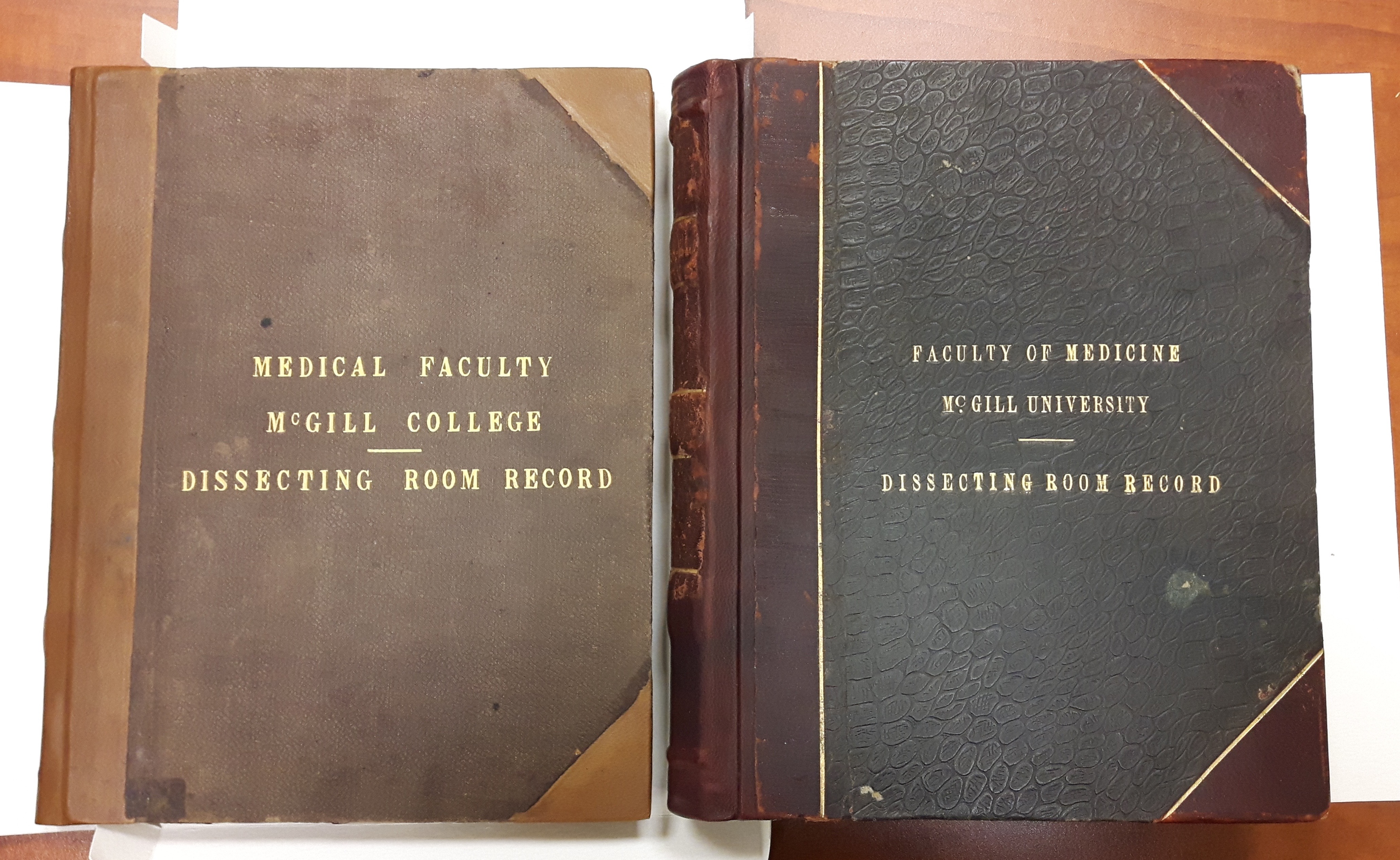

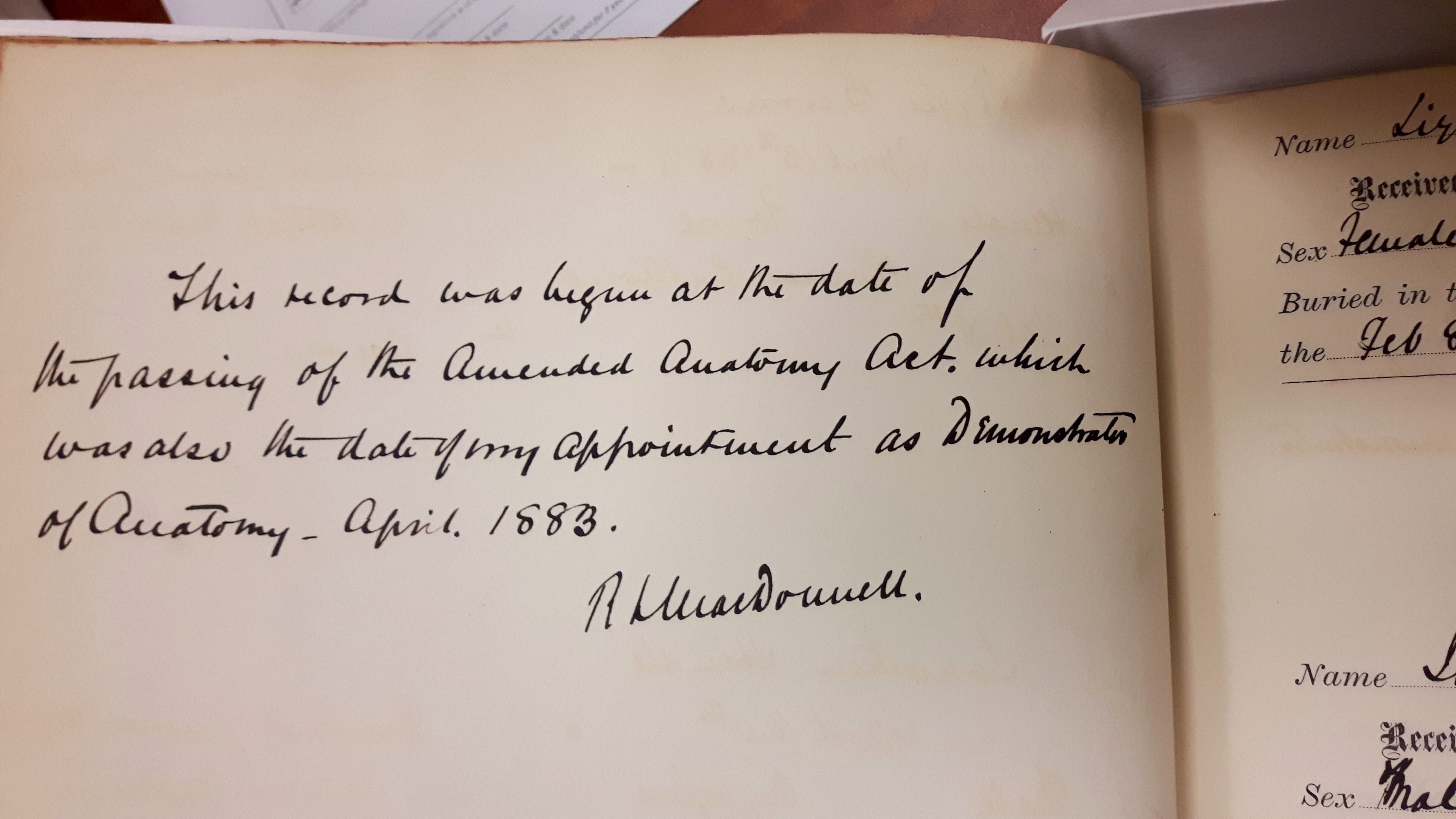

In 1883, a strengthened Anatomy Act put greater pressure on institutions to provide bodies to Montréal’s medical schools. In effect, by the twentieth century, any mention of body-snatching had all but disappeared. Yet, as noted in the early issues of The McGill Daily, the legacy of these “brave resurrectionists” lived on in the medical faculty for decades. Annually, students would celebrate “King Cook”, the medical building custodian who assisted students in sneaking unofficially obtained corpses on campus. These celebrations consisted of a parade down Saint Catherine Street and humorous theatrical productions, in which the famed Stephen Leacock was known to partake in.

Medical Building janitor King Cook dressed as John Bull, the patriotic symbol of Great Britain, with medical students, 1918. McGill Archives.

The notoriously rowdy “King Cook Celebration” was documented as last occurring in 1926, and since then the history of the medical student body-snatching has been largely forgotten. Although largely absent from official documents, the remaining first-person accounts reveal this morbid and fascinating period in McGill Faculty of Medicine history.

Sources:

Hanaway, Joseph, and Richard Cruess. “The Faculty of Medicine: 1874–85: The Osler Years.” McGill Medicine: The First Half Century, 1829-1885, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996, pp. 65–99, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt814n7.11.

Lawrence, D.G. “Resurrection and Legislation or Body-Snatching in Relation to the Anatomy Act in the Province of Quebec.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 32.5 (1958). Print.

Shepherd, Francis J. Reminiscences of Student Days and Dissecting Room. Montreal: publisher not identified, 1919. Print.

The McGill Student Publications Collection

Worthington, E D. Reminiscences of Student Life and Practice. Sherbrooke [Quebec: Printed for Sherbrooke Protestant Hospital by Walton, 1981.