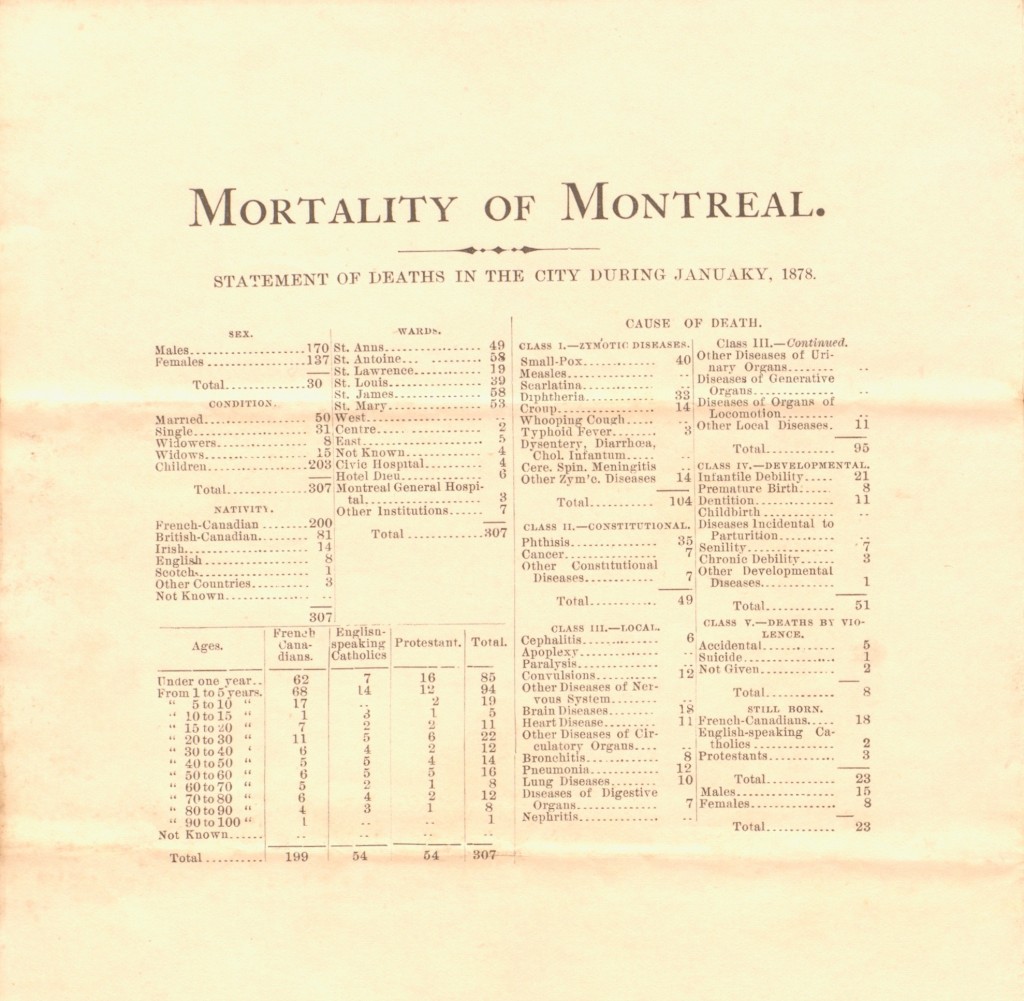

This historical snapshot of Montreal mortality statistics from the first month of 1878 was recently acquired by the Osler archives, as part of the John Bell fonds. At the time, McGill graduate John Bell had his own medical practice on Beaver Hill Hall and was also Physician to Montreal’s Protestant Infants’ Home. As a local physician, Bell would have received these bulletins on a monthly basis from the Department of Health. The distributed information contained in these bulletins was largely based on mortuary statistics acquired from the Catholic and Protestant Cemeteries.

Montreal in the 1870s was the most industrialized and populous city in Canada – with more factories, elevators, warehouses, mills and refineries than anywhere else. Unfortunately, the city’s growing population during the nineteenth century registered some of the highest mortality rates in North America – largely due to rapid settlement, poor unsanitary living conditions, and disease.

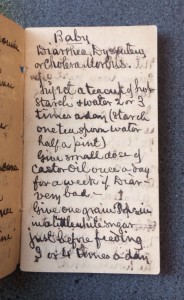

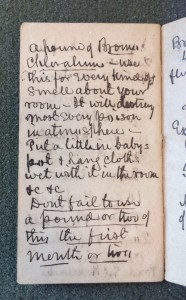

In particular, the infant mortality rate in Montreal was notoriously high, with statistics reaching upwards to a quarter of all newborn children dying within the first twelve months. Unsafe water and a limited use of vaccines against diseases such as smallpox and diphtheria contributed to these numbers.

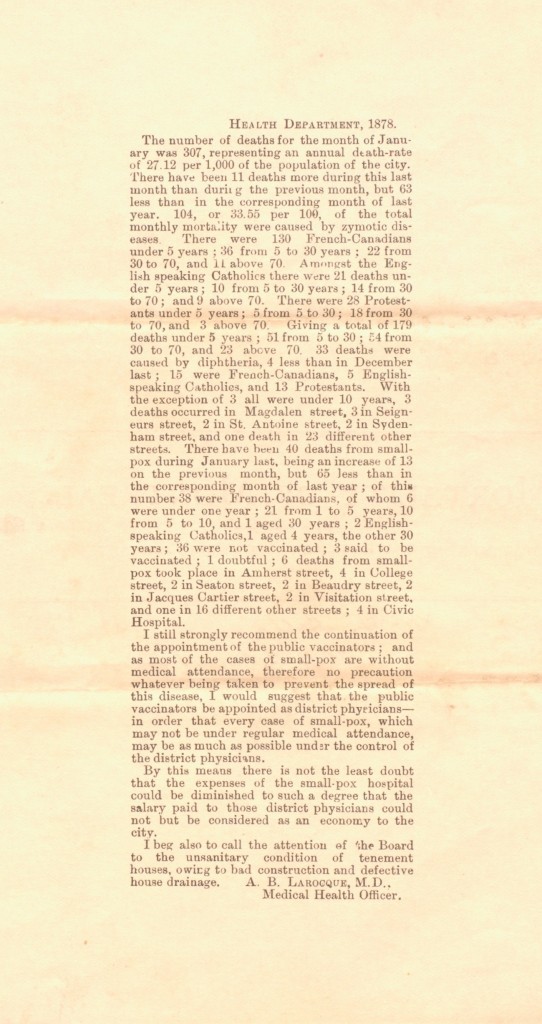

The smallpox epidemic of 1885-86 that completely ravaged Montreal’s population and spread across Quebec occurred approximately seven years after this bulletin was published. The Health Department’s warnings and recommendations attached here cast a foreboding light on a serious growing concern for the spread of disease, calling for an increase in district vaccinations.

“I still strongly recommend the continuation of the appointment of the public vaccinators; and as most of the cases of smallpox are without medical attendance…I would suggest that the public vaccinators be appointed as district physicians – in order that every case of smallpox…may be as much as possible under the control of the district physicians” – Medical Health Officer, A. B. Laroque, 1878.

For researchers who are interested in the history of Montreal health and mortality statistics, this “Mortality of Montreal” document could serve as an ideal starting off point, or addition to one’s research. The Osler Library also houses numerous decades worth of nineteenth century provincial and municipal health records, reports, and journals such as the annually published Report of the Board of Health of the Province of Quebec and Report of the Sanitary State of the City of Montreal. All are available to view by consultation at the Osler Library.

In addition, local newspaper articles related to this topic can be found on microfiche and online, such as Montreal Herald articles from the 1860s to 1880s – some of which have been digitized by the Department of Mathematics and Statistics at McGill. The articles linked below discuss the concern over Montreal’s mortality rates at the time, and they also show the adversarial dialogue surrounding the statistics.

“The Mortality of Montreal.” The Montreal Herald, January 20, 1870.

“Vital Statistics.” The Montreal Herald, October 28, 1869.

“Montreal Mortality.” The Montreal Herald, November 30, 1869.