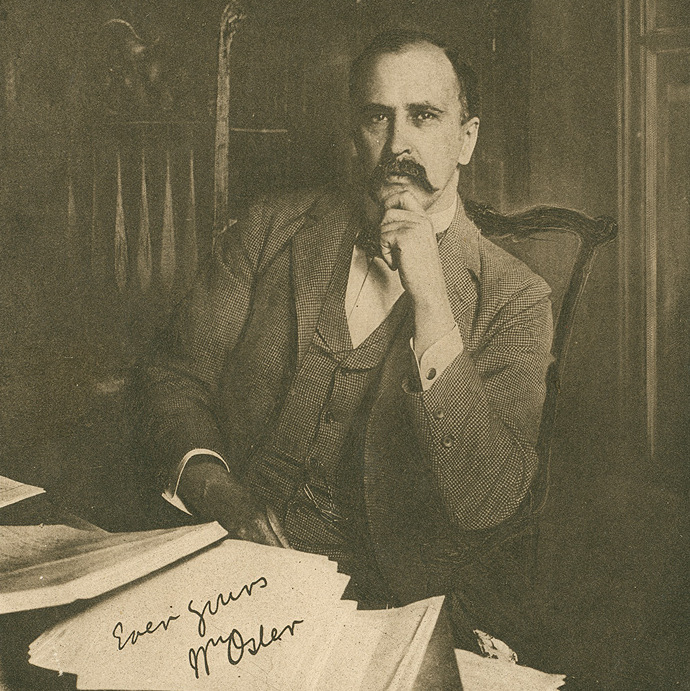

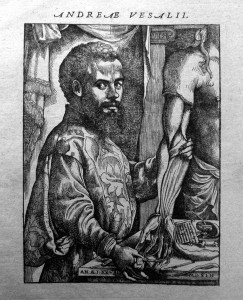

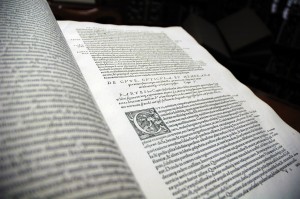

Image 1: Author Portrait from the Fabrica

Andreas Vesalius was born on the last hour of the last day of 1514 in Brussels to a family that had seen four generations of physicians before him. Of particular notoriety, his grandfather was the personal physician to the Emperor Maximilian. At an early age Andreas’s mother sent him to attend university in the neighboring city of Louvain, where he went on to develop an affinity for ancient languages and human anatomy. The few human dissections Vesalius witnessed at Louvain were his first exposure to the value of using cadavers to learn about the human body. He began his own anatomical studies by dissecting the bodies of mice, moles, rats, dogs and cats – the only readily available tissues he could practice with at the time. Vesalius travelled to Paris in 1533 to obtain a proper medical education from the world-renowned University of Paris, which had already established itself as a center for medical education. One of his mentors was Jacobus Sylvius, who is known for being the first professor of medicine in France to use a human cadaver for anatomical lessons. While his lectures were indeed well attended, he professed a kind of blind faith for the works of Galen. Whenever a body part in his demonstrations deviated from the ancient’s writings, he would simply say that the human body has changed since Galen’s time. Vesalius eventually came to the conclusion that the only way his knowledge could rival that of the Alexandrian teachers, those pioneers into the world of human dissection, would be if he also took human dissection into his own hands. He began by studying human bones taken from cemeteries around Paris. Eventually his knowledge of the skeletal system became so complete that he was said to be able to identify a bone while completely blind-folded. This ultimately won him the respect of the entire faculty and he, too, began to teach.

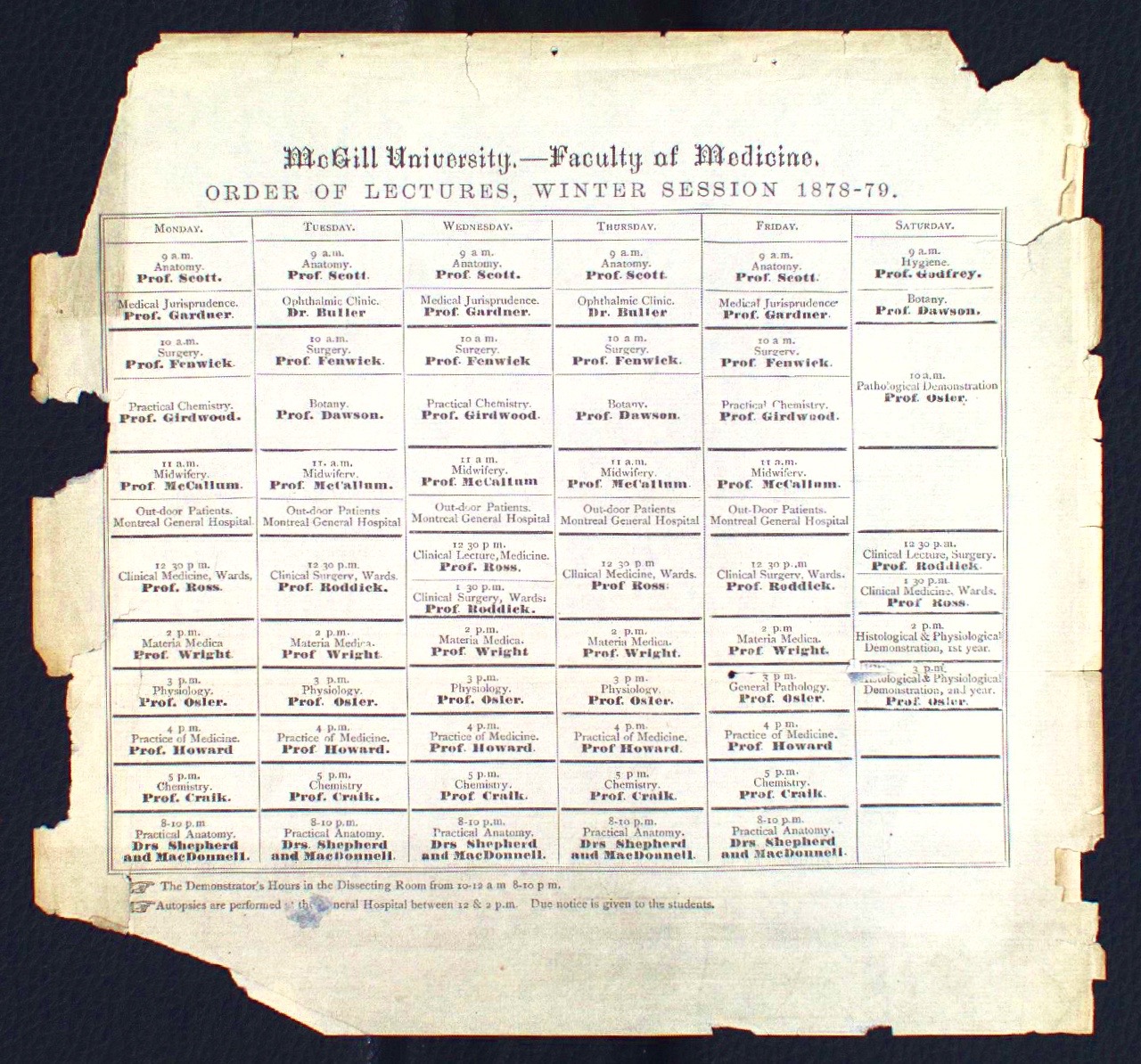

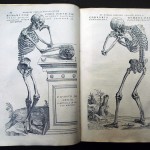

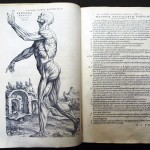

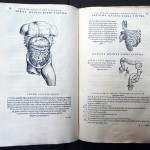

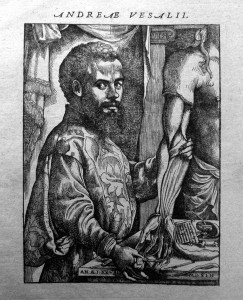

After some years of lecturing in Louvain and then Padua, Vesalius began his 3 years of tireless effort to compile the masterpiece De humani corporis fabrica libri septum. The first edition of the work, published in 1543, is upheld as the cornerstone of modern anatomy and holds a coveted place in the history of medicine. It has been said that in 1543, with the publishing of the Fabrica, a revolution of sorts occurred. While it was indeed the most accurate, best illustrated, and complete anatomical treatise that had even been produced, it also mostly rejected the teachings of Galen that had been accepted as medical fact for the thirteen centuries prior. The beautiful composition of De humani corporis fabrica libri septum was a huge step forward for both anatomists and artists, alike. This copy of the Fabrica, now housed in the Osler Library of the History of Medicine, was printed on the press of Johannes Oporinus of Basel in 1543 (when Vesalius was only 28 years old). While Johannes was also at the center of other noteworthy publications, such as the first Latin edition of the Koran in 1542/43, the Fabrica now certainly stands out as the most famous. Prior to Vesalius, human dissection was only conducted within universities by a professor who read aloud a Latin text (which at this time was almost always Galen) while a barber-surgeon handled the cadaver to show the body part being discussed. The purpose was not to verify these ancient writings, but rather to demonstrate their unquestioned knowledge. Medical illustration at the time was not based in a naturalistic representation of anatomy, but stylized schematic diagrams that correlated with the text rather than what was witnessed. When Vesalius published the Fabrica and scholars began to understand how he developed it, these tendencies began to radically change.

The illustrations of the Fabrica were so ground-breaking that plagiarized versions began to emerge in Western Europe almost immediately after the first print. Works appeared from various authors between the years of 1553 – 1564 that out-right copied the illustrations from Fabrica and substituted Vesalius’s text with words of their own. The publication of the first two editions of Fabrica didn’t go without controversy in terms of their contents. Sylvius, Andreas’s Galenist mentor from the University of Paris, had gathered a camp of supporters that drastically opposed Vesalius’s radical departure from the words of the ancients. These scholars claimed that Vesalius was effectively falsifying Galen’s words and regularly criticized him for his departures from the lessons of the ancients. After the publishing of the Fabrica, Vesalius continued to delve deeper into his own anatomical understandings by continuing with his human dissections until the end of his days (apart from a consultant physician job meant to support himself). However, the exact events of these last days are shrouded in mystery. Rumor has it that when Vesalius was conducting dissections in Spain, he opened the chest of one individual to only find that the heart was still beating. What he thought to be a dissection suddenly became a vivisection, which was entirely illegal to perform on a human being. Supposedly he was sentenced to death by the inquisition, but the king commuted his sentence on the grounds that he make a trip to Jerusalem to expiate his sins. While the journey to the Holy Land was accomplished safely, Vesalius fell ill on the return trip and died on the island of Zante (present day Zakynthos) on October 15th, 1564. He was survived by his wife and daughter but, due to the location where he died, he was buried in an unmarked grave rather than be returned.

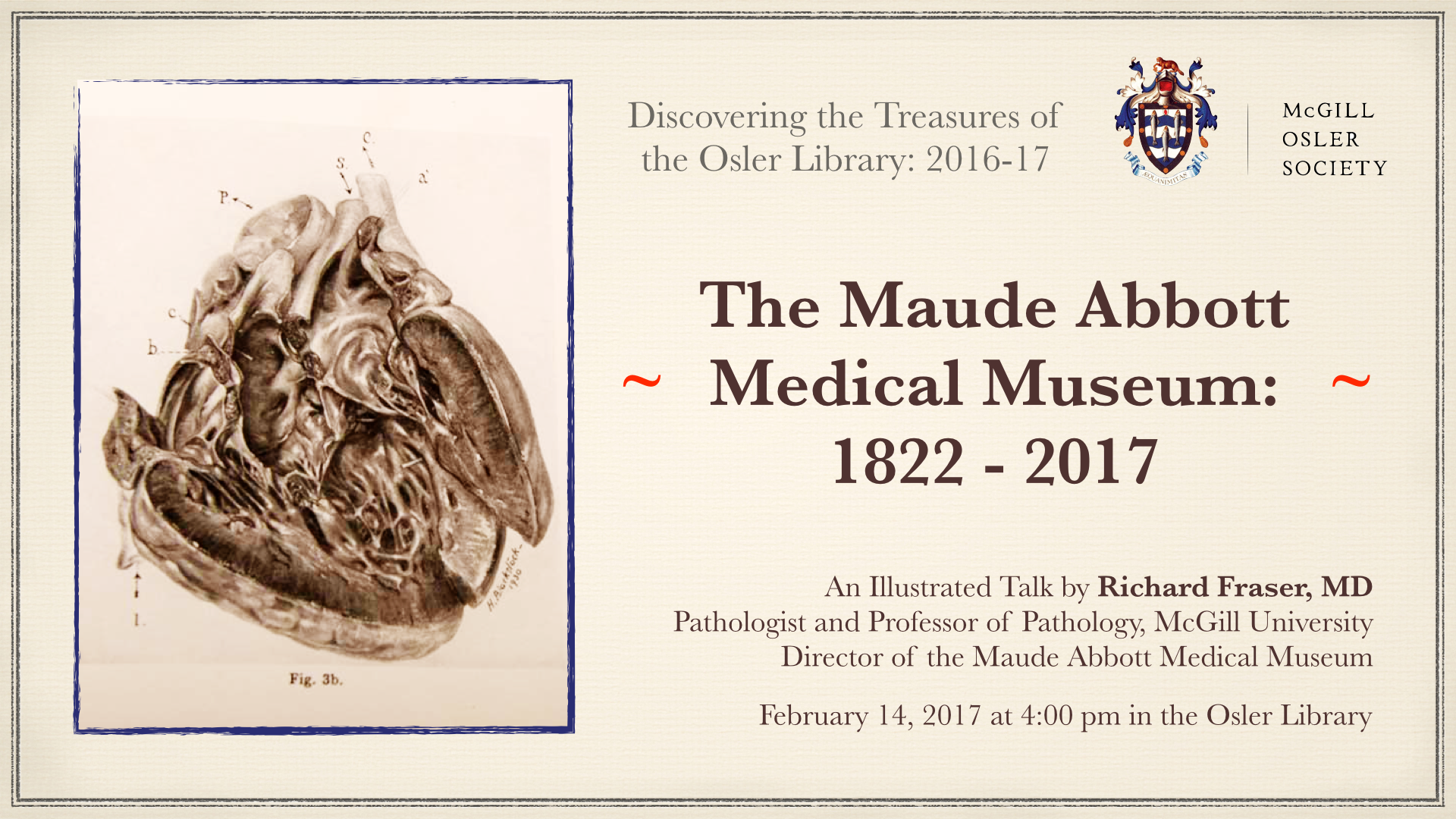

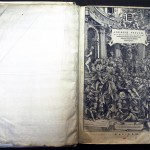

Image 2: A page from the Fabrica

Despite his inglorious death, his De humani corporis fabrica libri septum has allowed Vesalius’s name to live in infamy. The Fabrica holds a special place of significance in the history of science since illustrations and scientific text had never been brought together before in such a way. The use of the printed book as a medium for scientific knowledge in terms of both text and illustrations was considered to be ground-breaking at the time. Dr. Cushing, who published a biography about William Osler, also published a biography about Vesalius in 1943 to commemorate the 400 years since the creation of the 1st edition of the Fabrica. To be in possession of an original copy of the Fabrica is certainly a privilege, considering any surviving copies of the 1st edition prints are not extremely plentiful in contemporary times. Brown University’s John Lay Library is known to have received a copy which is bound in tanned human skin. Two other copies have been sold at auctions, one of which sold for $412,994 and the other – the only fully colored copy known to exist – for $1,652,500. Luckily William Osler came across many 1st edition copies of the Fabrica as they were plentiful around the turn of the twentieth century. In the Bibliotheca Osleriana, Osler explained that it would be a regular occurrence to see these masterpieces with price tags ranging from £10 to £20. Interestingly enough, Sir William didn’t entirely credit the emergence of modern anatomy to Vesalius. Rather, he gave that credit to the Alexandrians in making the claim that Vesalius “remade” their teachings. Osler explained that during his career 6 copies had come through his hands and were given away to various libraries. The importance he ascribed to a 1st edition Fabrica is simple: it is the manifestation of a moment when the production and dissemination of scientific knowledge underwent a critical turning point. In speaking about this copy of the Fabrica, Sir William wrote the following: “I am glad to be able to send this beautiful copy of the first edition to the library of my old school, in which anatomy has always been studied in the Vesalian spirit— with accuracy and thoroughness. William Osier. Rome, March 9th, 1909.”

Sources

Ball, James M. Andreas Vesalius, the Reformer of Anatomy. Saint Louis: Medical Science Press, 1910. Print.

Christie’s. Sale 8002, Lot 70. 23 November 2011.

Christie’s. Sale 8854, Lot 213. 18 March 1998.

Fulton, John F. Vesalius four centuries later: Medicine in the eighteenth century. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press. Print.

Hansen, Kelli. William Osler, W.J. Calvert, and MU’s Vesalius. University of Missouri. 2014. Online.

Oldfield, Philip. Vesalius at 500. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014. Print.

Osler, William. Bibliotheca Osleriana: A Catalogue of Books Illustrating the History of Medicine and Science. Montreal [Que.: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1969. Internet resource.