If you have taken or are currently taking any kind of class in the health sciences at McGill, you will have probably heard about a term called Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) or Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM). EBP/EBM is about “integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from a systematic search.”1 As the librarian for Undergraduate Medical Education (UGME), I am embedded in the EBM portion of first year courses, where we often show students this diagram:

This a classic visual representation of Evidence-Based Medicine and shows how EBM sits at the intersection of three essential components:

- Clinical Expertise: this refers to the clinician’s own skills, knowledge and past experiences in treating patients

- Best Evidence: this refers to the most current and relevant research available, often from rigorous clinical trials and systematic reviews

- Patient Preferences and Values: these refer to the patient’s own experiences, concerns, needs and cultural beliefs that they bring to the encounter.

If any one of these elements is missing or ignored, clinical decision making becomes less effective and the quality of care you are providing diminishes. That’s why it’s so important to consider the broader context, including how recent political shifts – regardless of where you fall on the political spectrum – have influenced the way we understand, access and apply evidence in healthcare today.

Since arriving in office back in 2016, the Trump Administration has issued executive decisions that pose a serious threat to one of the EBM elements – Best Evidence. And if you’re thinking that it doesn’t matter because we’re in Canada, think again. These decisions have implications on a global scale.

Politicization and Decimation of Public Health Agencies

Public health is a pretty self-explanatory concept – it’s all about the protection of people in the community, aimed at promoting healthy behaviours, preventing disease and protecting the public. In Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada and Health Canada work together to keep us healthy. The United States has several agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), among others.

When public health agencies and departments are politicized, the credibility of health recommendations can be undermined, leading to public mistrust, confusion among healthcare providers, and challenges in maintaining evidence-based practice.

In December of 2017, The Washington Post reported that the CDC was given a list of words that were forbidden, including “evidence-based” and “science-based”.2 I don’t know about you, but personally I don’t think a person who doesn’t trust the word science instills a lot of confidence. Back in the 2020, Trump-appointed HHS officials tried to block the CDC from releasing data in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) because the administration believed the CDC used language that could hurt the president’s chances for re-election.3 Thousands of public health officials rely on that report to inform their own practice and decisions in their communities.

More recently, in the early months of 2025, Trump gutted key health agencies, slashing funding and firing staff at an alarming rate. Newly appointed Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. announced that 10 thousand jobs were being cut at HHS alone. Additional cuts were reported at the CDC, the FDA, and the Agency for Health Research and Quality, which lost half its staff.4

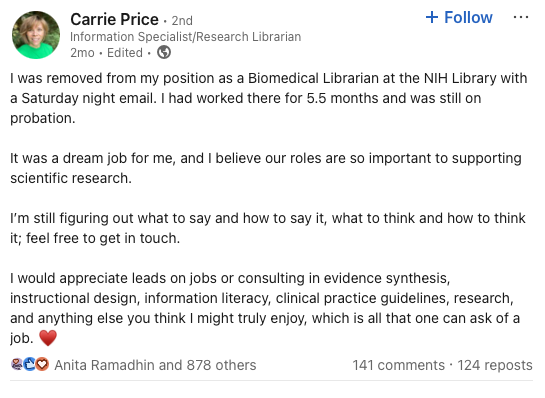

Among those who were unceremoniously fired was Carrie Price (not that Carey Price, Habs fans…), a Biomedical Librarian at the National Institutes of Health. Her post on LinkedIn went viral, with hundreds of librarians who work with clinicians supporting her and sounding the alarm about the importance of librarians for founding sound research.

Public health works best when smart, dedicated people — researchers, clinicians, librarians, and public health officials — have the tools and support they need to keep us safe. When funding gets slashed and expertise gets sidelined, it’s not just bad for science — it’s bad for everyone. Evidence-based practice relies on good information, and good information doesn’t just appear out of thin air. It’s built by teams of people working behind the scenes, often quietly and carefully, to make sure what you hear from your doctor, pharmacist, or public health office is actually trustworthy.

Changes in Research Priorities and Funding

Politics doesn’t just shape laws; it also shapes what kind of science is conducted. When federal funding priorities shift, so do research agendas at health agencies. One administration might pour money into a certain disease, while the next focuses almost entirely on another, or cuts programs altogether. An administration’s research priorities play a role in which questions get answered, which problems get solved, and which communities get left behind.

The Trump administration has never been a fan of climate change. The words themselves make people in the White House duck for cover. Through a series of executive decisions, Trump has pulled back climate change funding, withdrawing from the Paris Agreement and rolling back pollution and fossil fuel regulations, a decision which has major implications for respiratory diseases and weather-related health crises.5

Another thing the Trump administration doesn’t like: gender. They have made it very clear that they will not be spending money on research related to sexual and gender minorities, putting the health of these groups at risk. All transgender-related research was halted at the NIH6 and suddenly, scientists like Theo Beltrán and Jace Flatt, who have spent decades dedicating their lives to these fields, found themselves in limbo.

So what does this have to do with evidence-based medicine? A lot, actually. EBM depends on having high-quality, up-to-date research to guide decisions. But if certain areas of science aren’t being funded, that evidence might not exist in the first place. If climate-related health risks or gender-related topics aren’t being studied, clinicians are left with gaps in the evidence and that makes it harder to give patients the best possible care. If the research isn’t there, the “best available evidence” part of EBM starts to fall apart.

Inconsistent Guidelines

A clinical practice guideline is a set of evidence-based recommendations designed to help healthcare professionals make informed decisions. They’re developed by experts, who systematically review the best available evidence to help guide clinicians to what’s most likely to work, what to look for, alternate options, etc. They help with the standardization of care in that they ensure that patients receive consistent and high-quality treatment no matter where they are and who is treating them. But what happens when these guidelines collide with politics?

Reproductive healthcare is a prime example. Since the overturning of Roe v. Wade, clinicians in many U.S. states have found themselves caught between evidence-based recommendations and restrictive state laws. In some cases, treatment for miscarriages or ectopic pregnancies has been delayed out of fear of legal repercussions, even when the medical guidelines are clear and the patient’s health is at risk.7

Organizations like The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the World Health Organization (WHO) continue to publish guidance that supports timely, patient-centered care, but in politically charged environments, following those recommendations isn’t always possible. The result is a broken system where the quality of care can depend more on geography than science, a situation that undermines the very foundation of evidence-based medicine.

While these developments are happening south of the border, they still have implications here in Canada. Canadian clinicians and researchers often rely on U.S.-based studies, guidelines, and collaborations. When reproductive health research is restricted or politicized in the U.S., it can slow progress for everyone. Even though abortion remains legal in Canada, access varies widely by province, and we’re not immune to political pressure. These moments remind us how important it is to protect evidence-based guidelines and ensure healthcare decisions stay grounded in science, not ideology.

Final Thoughts

At the heart of it, evidence-based medicine is about trust — trust that the research behind our care is solid, that guidelines are grounded in good data, and that health decisions are made with patients’ well-being in mind. Librarians are a big part of that picture: we help students learn how to find reliable evidence, support clinicians in staying current, and quietly make sure the information pipeline runs smoothly. When politics starts to mess with science, things can get murky.

The good news is that there are still a lot of people, from researchers to clinicians to librarians, working hard to keep the evidence strong and the science honest! Even when it might seem like we’re on shaky ground, the foundation of EBM is still standing — and we’re here to help keep it that way.

- Sackett, D. L., Rosenberg, W. M., Gray, J. A., Haynes, R. B., & Richardson, W. S. (1996). Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 312(7023), 71–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71 ↩︎

- Sun, L. H., & Eilperin, J. (2017). CDC gets list of forbidden words: Fetus, transgender, diversity: Agency analysts are told to avoid these 7 banned words and phrases in budget documents. Washington, D.C. ↩︎

- Dyer, O. (2020). Trump appointees tamper with renowned CDC publication, claiming that scientists are trying to “hurt the president”. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 370, 1–2. ↩︎

- Looi, M.-K. (2025). Trump’s 10 000 job cuts spark chaos in US health services. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 389, r682. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.r682 ↩︎

- Wagatsuma, K. (2025). Implications of President Trump’s Second Term Executive Orders on Global and Public Health. International Journal of Public Health, 70. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2025.1608402 ↩︎

- Kozlov, M. Exclusive: Trump White House directs NIH to study’regret’after transgender people transition. Nature. ↩︎

- Roper, K. L., Robbins, S. J., Day, P., Shih, G., & Kale, N. (2024). Impact of State Abortion Policies on Family Medicine Practice and Training After Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Annals of Family Medicine, 22(6), 492–501. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.3183 ↩︎