April may be a busy time while you are completing your term papers and exams. It may also be a great time to reflect and determine what you want to accomplish in the upcoming summer vacation. How about uplifting your academic writing skills? No matter what level of study you are doing or what role you are playing in academia, good writing undoubtedly makes a positive contribution to your work. Not only does it help to make your ideas more precise and persuasive, but also it aids in your reasoning, analyzing, and critical thinking.

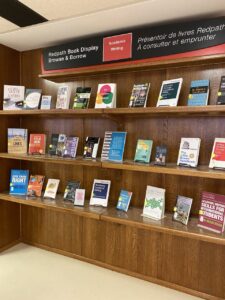

With that in mind, the McGill Library created a virtual book display entitled “English & Academic Writing”, consisting of recent print books, ebooks, e-videos and website resources on academic writing and English communication. They are useful for both instructors and students of various disciplines, including those whose mother tongue is not English. Selected print titles are now available for borrowing on the Redpath Book Display on the main floor of the Redpath Library (aka. the northern part of the Humanities and Social Sciences Library) during the entire month of April.

Here are some of the titles that you may want to start with:

100 tips to avoid mistakes in academic writing and presenting, Adrian Wallwork & Anna Southern, 2020, Springer

This ebook contains one hundred typical mistakes relating to papers, proposals, oral presentations, and correspondence with editors, reviewers, and editing agencies. While it is primarily intended for non-native English speaking researchers, it is also useful for those who are revising their works in order to have them published.

How to fix your academic writing trouble: a practical guide, Inger Mewburn, Katherine Firth, and Shaun Lehmann, 2019, Open University Press

This print book explains common feedback students receive from their instructors of a writing course, such as “Your writing doesn’t sound very academic” and “Your writing doesn’t flow”. It also provides advice on how to fix those issues.

Writing for engineering and science students: staking your claim, Gerald Rau, 2020, Routledge

This ebook is a practical guide for both international students and native speakers of English undertaking either academic or technical writing. It uses writing excerpts from engineering and science journals to explore characteristics of a research paper, including organization, length and naming of sections, and location and purpose of citations and graphics. It covers different types of writing, including lab reports, research proposals, dissertations, poster presentations, industry reports, emails, and job applications.

Academic writing for university students, Stephen Bailey, 2022, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group

This print book is designed to help with writing essays, reports and other papers for coursework and exams. It consists of four parts: The Writing Process: From finding suitable sources, through to editing and proofreading; Writing Types: Practice with common assignments such as reports and cause-effect essays; Writing Tools: Skills such as making comparisons, definitions, punctuation and style; and Lexis: Academic vocabulary, using synonyms, nouns, adjectives, verbs and adverbs.

“They say / I say”: the moves that matter in academic writing: with readings, Gerald Graff, Cathy Birkenstein, Russel K Durst, and Laura J Panning Davies, 2021, W.W. Norton & Company

This text has been used in many writing courses to teach students how to structure a scholarly conversation while building their own arguments. It provides practical rhetoric templates that are useful for citing different views in the literature, for example, “In discussions of………………, a controversial issue is whether……………… . While some argue that………………, others contend that………………. .” It is definitely a helpful guide for writing your literature review.

Becoming an academic writer: 50 exercises for paced, productive, and powerful writing, Patricia Goodson, 2017, SAGE

This print title is a workbook of 50 exercises, covering both linguistic basics (e.g. grammar and vocabulary) and writing specifics in different sections of an academic work, such as abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion and conclusion.

For those whose mother tongue is not English, also feel free to watch some e-videos listed in the “Study English” and “English Composition” series.

Since it takes effort and time to improve your writing, why don’t you start the journey with a book from our book display today?