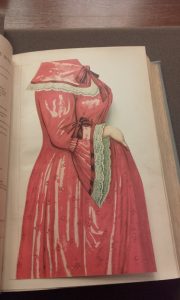

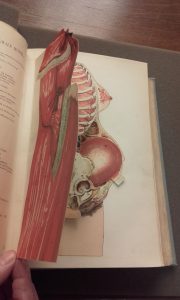

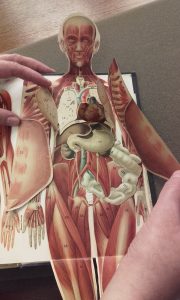

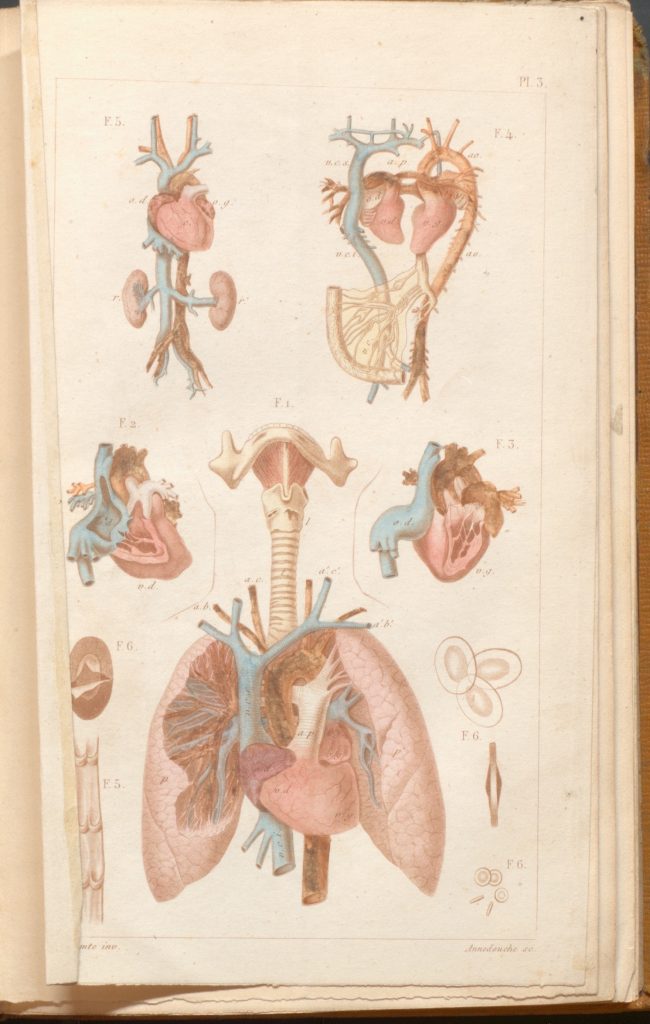

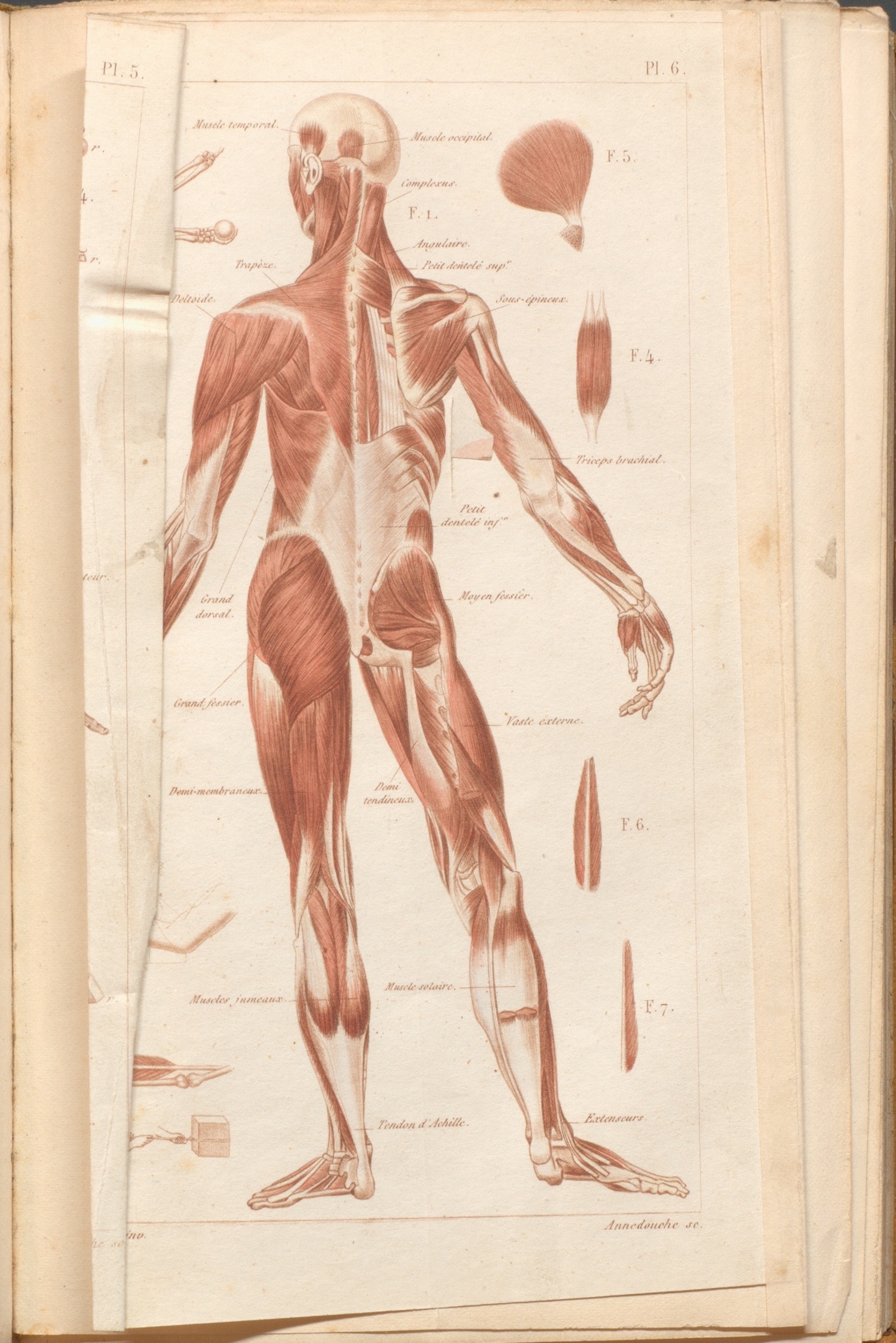

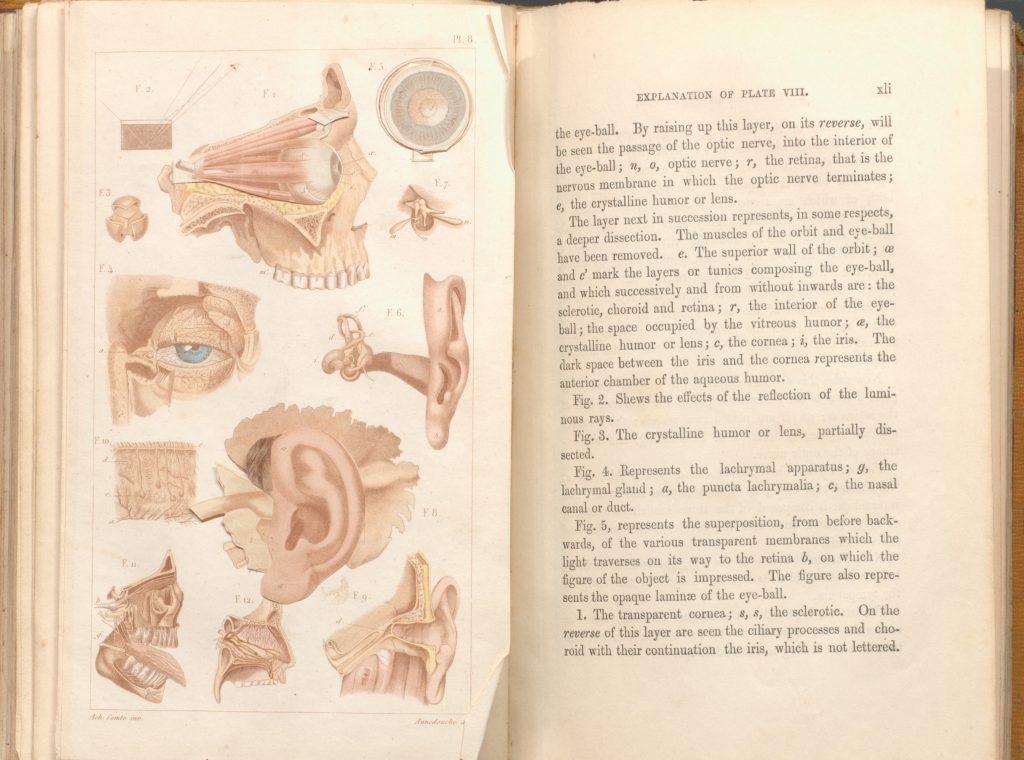

Pratiquée de manière assez confidentielle au Moyen Age, la dissection se développe au 16e siècle, notamment lorsque le pape Clément VII autorise son enseignement. La Renaissance est également marquée par un essor des livres dédiés à l’anatomie, et en particulier des livres animés. Les auteurs de l’époque rivalisent d’imagination et d’ingéniosité pour répondre à la soif de connaissance des curieux, des médecins et des étudiants. Ces ouvrages ont souvent un objectif pédagogique, ce qui explique le recours aux illustrations à volets qui permettent au lecteur de mieux visualiser l’organisation interne du corps humain: grâce à un système de volets, le lecteur peut en quelque sorte pratiquer lui-même une dissection en soulevant un à un les volets qui dévoilent à chaque fois une « couche » du corps humain.

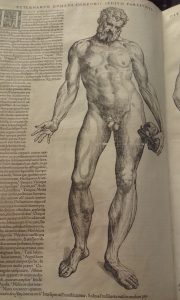

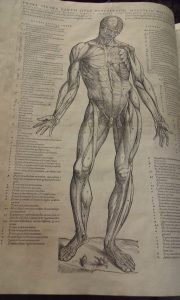

Parmi les anatomistes du 16e siècle, le médecin bruxellois André Vésale est sans doute le plus connu. Convaincu qu’il est difficile d’enseigner et d’apprendre l’anatomie sans pouvoir observer directement le corps humain, Vésale pratique régulièrement la dissection et fait paraître en 1543 son De humani corporis fabrica, qui renouvelle les connaissances en anatomie depuis Galien.

Dans son Epitome, supplément à la Fabrica destiné essentiellement aux étudiants en médecine, Vésale propose lui aussi une sorte de livre animé : plusieurs planches anatomiques de l’Epitome peuvent être découpées par le lecteur afin de reconstituer in fine un corps humain en trois dimensions. En effet, comme l’explique Jacqueline Vons, l’Epitome contient « deux planches constituées de plusieurs dessins que l’étudiant doit découper et coller sur d’autres figures afin d’obtenir, par superposition, un corps humain en trois dimensions. Le texte accompagnant ces deux planches est l’équivalent d’un mode d’emploi, d’une notice qui doit guider pas à pas l’étudiant dans son travail de recomposition. C’est déjà une méthode pédagogique inter-active, qui consiste à s’adresser à un étudiant virtuel, en développant une forme de dialogue entre le maître et le disciple » (1).

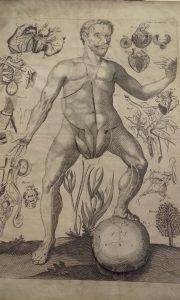

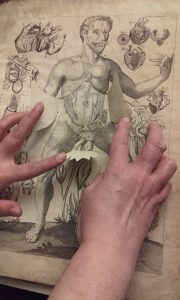

Un autre exemple célèbre de livre animé est le Pinax microcosmographicus de Johann Remmelin, paru au début du 17e siècle et réédité à plusieurs reprises (la bibliothèque Osler en possède d’ailleurs deux exemplaires du début du 18e siècle). Il permet de découvrir l’anatomie masculine et féminine grâce à des illustrations à volets. La bibliothèque de l’université de Columbia a récemment numérisé cet ouvrage et a mis en ligne une vidéo très intéressante qui montre le fonctionnement de ces illustrations anatomiques à volets.

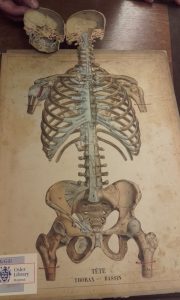

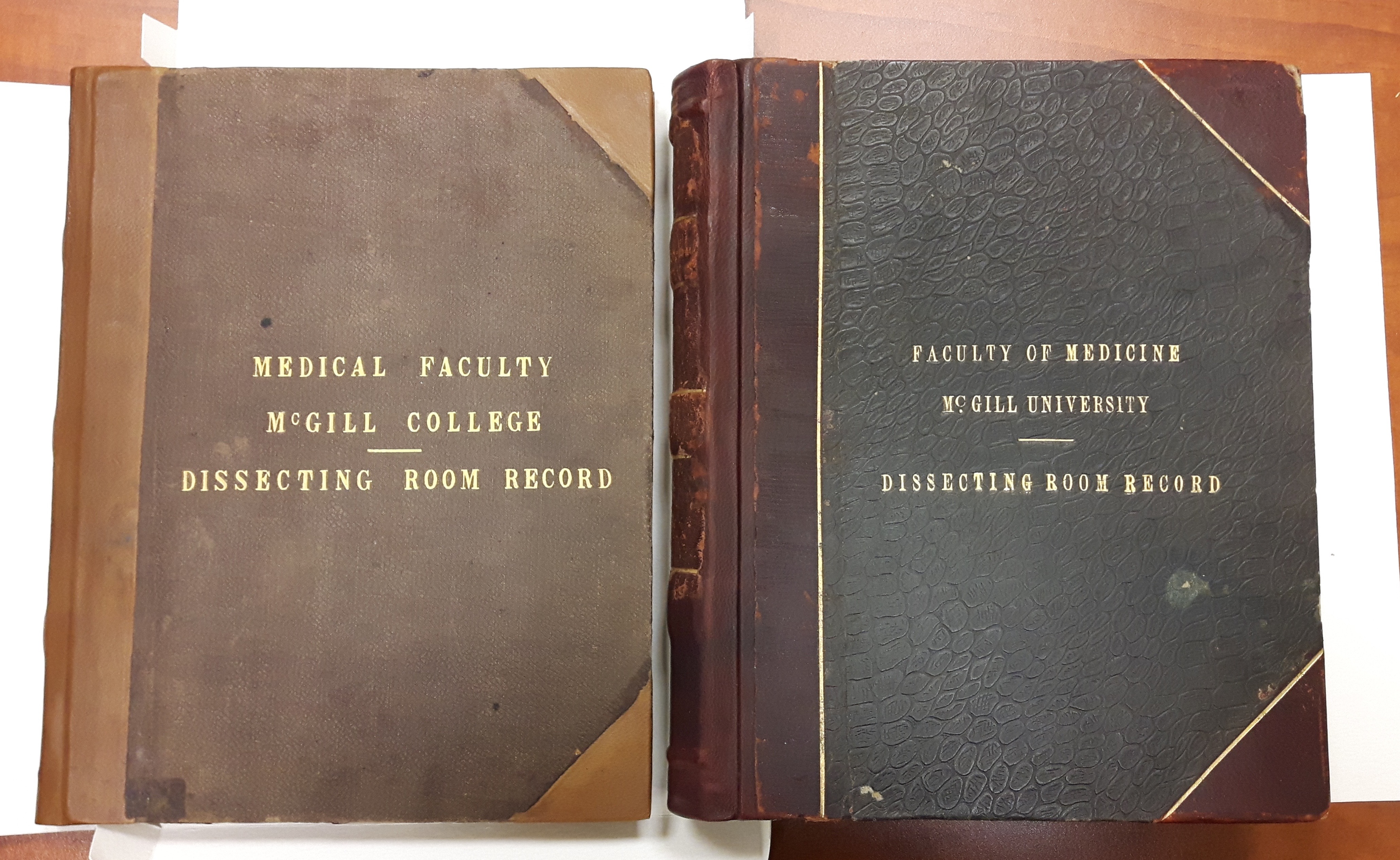

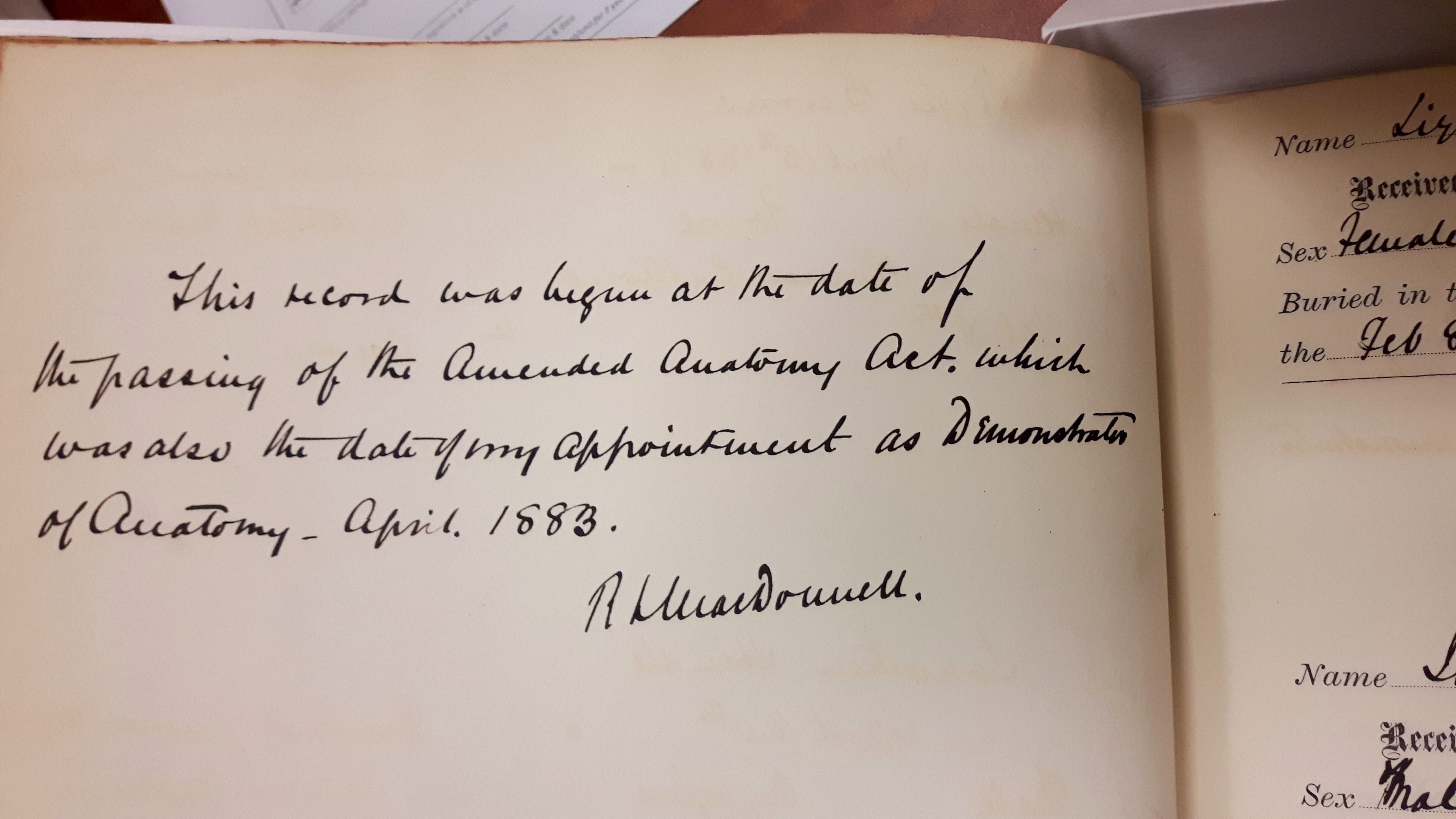

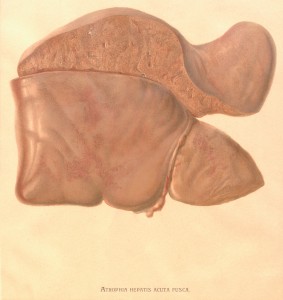

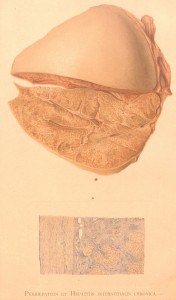

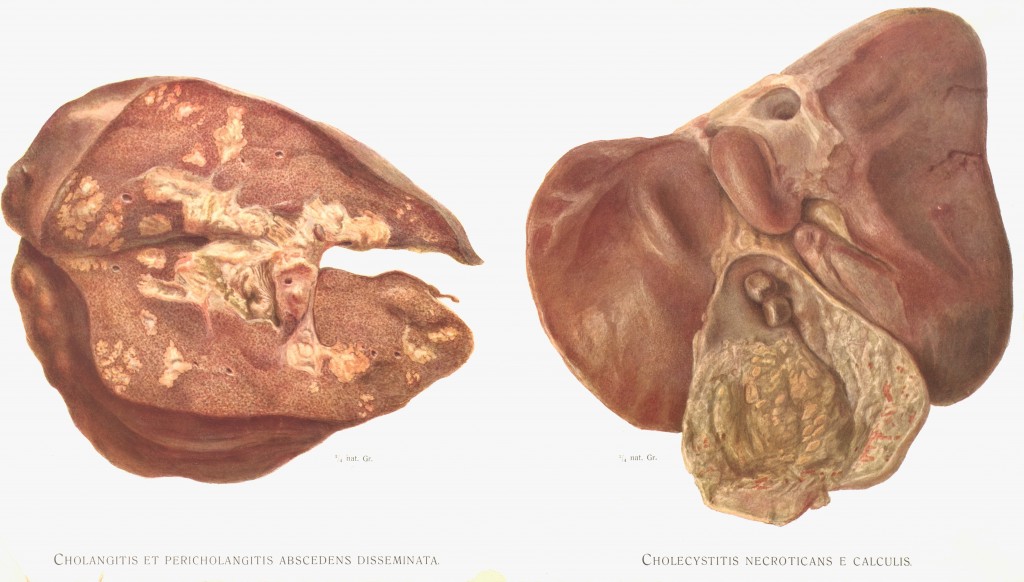

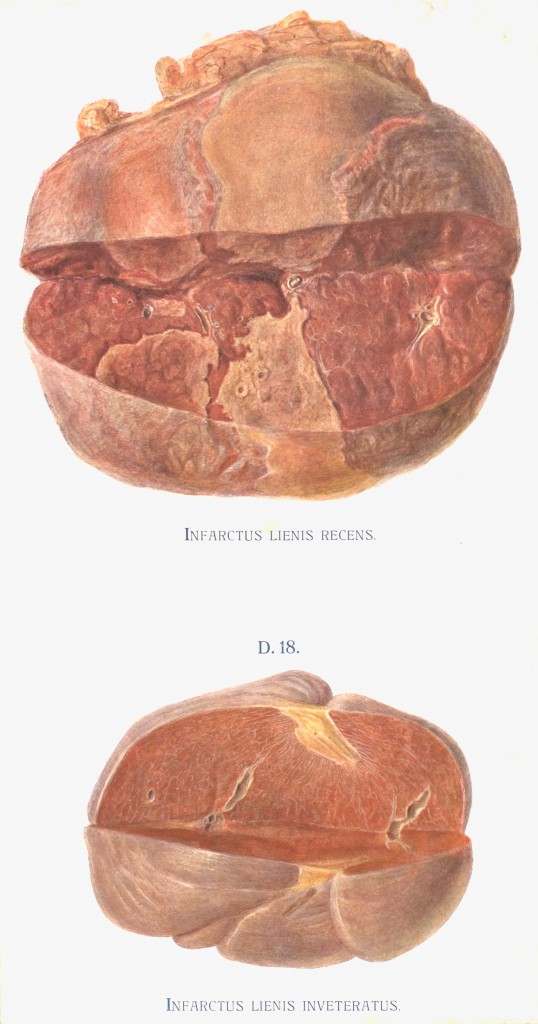

La pratique du livre anatomique à volets se perpétue et atteint son apogée au 19e siècle, quand les techniques d’impression en couleur se perfectionnent et se développent. Nous vous présentons ici quelques exemples issus de nos collections.

Mais les illustrations à volets ne se limitent pas au livre : certaines planches anatomiques utilisent le même procédé. La bibliothèque Osler a par exemple fait récemment l’acquisition d’une planche anatomique sur bois du 19e siècle, sans doute utilisée pour l’enseignement, qui représente un corps masculin presque à taille réelle, et qui par un système de volets maintenus par des languettes amovibles en métal, permet d’avoir la vision interne du corps humain (muscles, tendons, organes, os…).

Notes:

(1) Vons J., « L’Epitome, un ouvrage méconnu d’André Vésale (1543) », Histoire des sciences médicales, XL, 2, 2006, p.177-189, disponible en ligne [consulté le 12/04/2017].

Bibliographie :

Binet J.-L., « Traités d’anatomie », Bibliothèque numérique Medic@, disponible en ligne [consulté le 19/04/2017].

Carlino A., Paper bodies: a catalogue of anatomical fugitive sheets (1538-1687), London, Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 1999.

Columbia University Medical Center, « A medical pop-up from the 17th century”, disponible en ligne [consulté le 19/04/2017].

Duke University Libraries, « Animated anatomy », 2011, disponible en ligne [consulté le 12/04/2017].

Van Wijland J., « Usages des papiers découpés dans l’illustration anatomique des XVIe-XVIIe siècles », disponible en ligne [consulté le 19/04/2017].

Vons J., « L’Epitome, un ouvrage méconnu d’André Vésale (1543) », Histoire des sciences médicales, XL, 2, 2006, p.177-189, disponible en ligne [consulté le 12/04/2017].

Vons J., « L’anatomie au 16e siècle », Bibliothèque numérique Medic@, disponible en ligne [consulté le 19/04/2017].