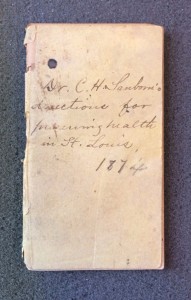

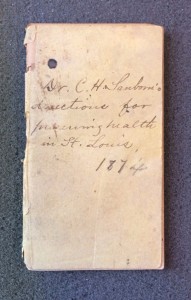

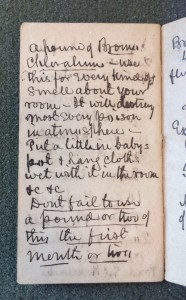

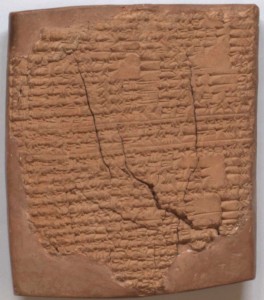

“Dr. C. H. Sanborn’s Directions for Preserving Health in St. Louis, 1874.” Osler Library Archives, P192

The Osler Library recently acquired a short manuscript booklet containing one doctor’s medical advice for patients moving out of town. Labelled “Dr. C. H. Sanborn’s directions for preserving health in St. Louis, 1874,” this tiny treatise provides advice and recipes for treating day-to-day complaints and guidelines for stocking the family medicine cabinet with the essentials.

Dr Charles H. Sanborn was a physician practicing in New Hampshire. Born in Hampton Falls in 1822, he graduated with an MD from Harvard Medical School in 1856 (1). He practiced medicine for over forty years in his hometown, where he also served as a Justice of the Peace and in local government (2). This autograph booklet appears to have been written by him for a family of three moving from New Hampshire to St. Louis, Missouri.

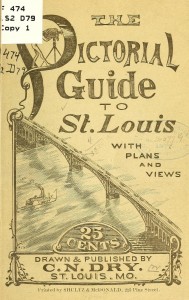

During the second half of the 19th century, St. Louis was undergoing a population explosion that would make it the fourth largest city in the U.S. after New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago. Expanding sectors, such as the cotton industry, and new railroad connections attracted an influx of new residents, perhaps including Dr. Sanborn’s patients. The city was prone to cholera and had lived through an epidemic that killed more than 3,500 residents in 1866, just eight years prior to the writing of Dr. Sanborn’s pamphlet. (3)

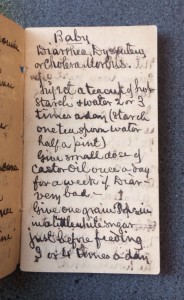

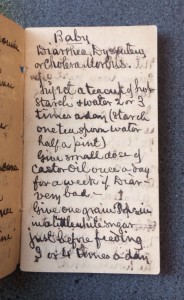

Fittingly, Dr. Sanborn’s medical advice concentrates heavily on cholera and other, less acute gastro-intestinal complaints associated with moving to new climes. The first page of medical instructions deals with how to treat “Diarrhea, Dysentery or Cholera Morbus” in the youngest member of the family. Remedies include starch, castor oil, bismuth, and, in the case of feverishness, veratrum viride, a highly toxic plant sometimes used during the 19th century in the treatment of typhoid fever and yellow fever.

Up until the late 19th and early 20th century, the majority of medical treatment took place at home. Popular printed medical manuals would have been readily available for purchase and families would have expected to care for their sick themselves:

The skills, knowledge, and responsibilities of laypersons and physicians overlapped; trained physicians were in a functional sense always consultants–with the primary caregiver a family member, neighbor, or midwife.(4)

In the case of Dr. Sanborn’s patients, the father was perhaps the one responsible for making medical decisions and treating his family. Advice for particular ailments is oftentimes labelled “Baby” or “Self & Wife,” and includes detailed instructions for treating croup, “lung fever,” measles, the “Shakes,” “weakness sinking etc. etc.,” sore throat, painful menstruation, inflamed eyes, burns, and bug bites. A list in the back of the book ennumerates the items that should be kept on hand for medical usage.

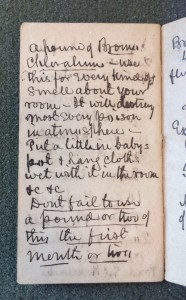

One of the chemicals on this list attests to the persistence of the miasma theory of disease into the second half of the 19th century, even as germ theory was beginning to emerge in scientific circles around the same time. Disease, it was thought, was transmittable by poisoned air, marked by a bad smell. Dr. Sanborn suggests the use of bromo-chloralum, a harsh disinfectant, to “destroy most every poison in the atmosphere.” He urges it to be used liberally in the baby’s room and all around the house: “Don’t fail to use a pound of two in the first month or two.”

One of the chemicals on this list attests to the persistence of the miasma theory of disease into the second half of the 19th century, even as germ theory was beginning to emerge in scientific circles around the same time. Disease, it was thought, was transmittable by poisoned air, marked by a bad smell. Dr. Sanborn suggests the use of bromo-chloralum, a harsh disinfectant, to “destroy most every poison in the atmosphere.” He urges it to be used liberally in the baby’s room and all around the house: “Don’t fail to use a pound of two in the first month or two.”

______________________________

This pamphlet is now available for consultation in our archives. You can find it listed on the Osler Library Archives database. For more information, please contact the library.

Further reading:

W. F. Bynum, Science and the Practice of Medicine in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

William G. Rothstein, American Physicians in the Nineteenth Century: From Sects to Science. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1972.

Charles E. Rosenberg. Our Present Complaint: American Medicine, Then and Now. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.

References

(1) Harvard University. Quinquennial catalogue of the officers and graduates, 1636-1930. (Cambridge, MA, 1930).

(2) Warren Brown, History of the Town of Hampton Falls, New Hampshire from the Time of the First Settlement within its Borders, vol. 1 (Manchester, NH, 1900.); The New Hampshire Register, Farmer’s Almanac, and Business Registry for 1871 (Claremont, NH, 1871).

(3) History of St. Louis, (1866-1904) http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=History_of_St._Louis_(1866%E2%80%931904)&oldid=638231408

(4) Charles Rosenberg, ed. Right Living: An Anglo-American Tradition of Self-Help Medicine and Hygiene. (Cambridge, 1992), 4.

About

About