This admonition has been heard by countless law-students while they were initiated into the intricacies of legal research. But what is “to note up”? – a bewildered first-year law student may ask.

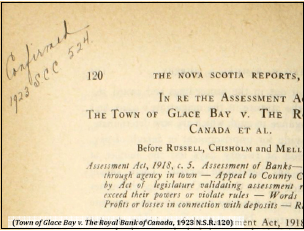

To note up is to look up the case’s history and to find if it was judicially considered in other cases. In the pre-internet time, law clerks and law librarians used to write the subsequent history of the cases on the margins of case reporters; thus, “noting up” the pages with references to the subsequent decisions. This is an example of an old noted up reporter from the Sir James Dunn Law Library (Halifax, NS).

We can trace back references to the practice of “noting up” to at least the 19th century, when The Law Times provided practitioners with “Notes for Noting Up,” and when proposals for legal textbooks included binding in a number of blank leaves specifically for noting up so that the textbooks could contain the latest law: “A member has suggested that the first text-book of the Society should be one which shall comprise the entire Practice of Law [….] It is further proposed that the volumes should be bound with blank leaves for noting up, and that in any digest of the Society a figure should refer to the page in the text-book in which the case or statute digested ought to be noted, so that the volumes should always keep pace with the existing law until a new edition is rendered necessary by the number of references” (Verulam Society, (1844) 3 The Law Times 275).

This post is derived from a discussion at the Canadian Association of Law Libraries listserv. Many thanks in particular to Lynne McNeill, Nikki Tanner, and Katie Albright for sharing their knowledge and to Natalie Wing to summarising the information for the benefit of CALL memebrs and for her kind permission to use it.