Par: George Yeryomin, étudiant à la Faculté de droit de l’Université McGill, assistant de référence à la Bibliothèque Gelber

Le droit civil en tant que tradition juridique s’étend sur plus de deux millénaires et demie d’histoire depuis la fondation de Rome, et ses principes et sa doctrine se trouvent contenus dans un grand nombre de lois et écrits monumentaux : les lois royales, la Loi des XII Tables, la codification monumentale de l’empereur Justinien, dont est issu le jus commune européen, élaboré et enrichi continuellement par tant d’œuvres et commentaires de jurisconsultes illustres, qui a subsisté pendant des siècles en tant que système de droit vivant jusqu’aux codifications nationales récentes (au XIXè siècle). La multitude des écrits formant la tradition et la doctrine civiliste est donc énormément riche et nombreuse. Mais cela veut-il dire que ces ressources doctrinales ne sont qu’accessibles à un nombre très limité de chercheurs? Bien au contraire, il y a une façon assez simple d’avoir accès aux extraits les plus pertinents de anciens docteurs et jurisconsultes qui ont servi de sources pour les compilateurs du Code civil, dont la lecture peut être d’une grande utilité pour comprendre le raisonnement derrière les règles expliquées de façon assez succincte par les codificateurs. Car il faut se le rappeler, le droit civil n’est pas issu du code, mais plutôt le code est l’expression synthétisée du droit civil.

La méthode que l’on vous propose comporte deux étapes, et aura pour but de vous faire découvrir une œuvre monumentale de la doctrine civiliste québécoise du XIXè siècle, La bibliothèque du Code civil de la province de Québec par Charles-Chamilly de Lorimier et Charles-Albert Vilbon1.

Première étape : trouver la concordance entre le CcQ et le CcBC

Une des façons de le faire est sur le site du CAIJ : https://elois.caij.qc.ca/CCQ-1991

Entrez l’article à propos duquel vous faites la recherche. La page consacrée à cet article vous indique l’équivalence dans le Code civil du Bas-Canada, s’il y en a une.

Dans l’exemple ci-dessous, nous cherchons les sources de l’art 1401 CcQ :

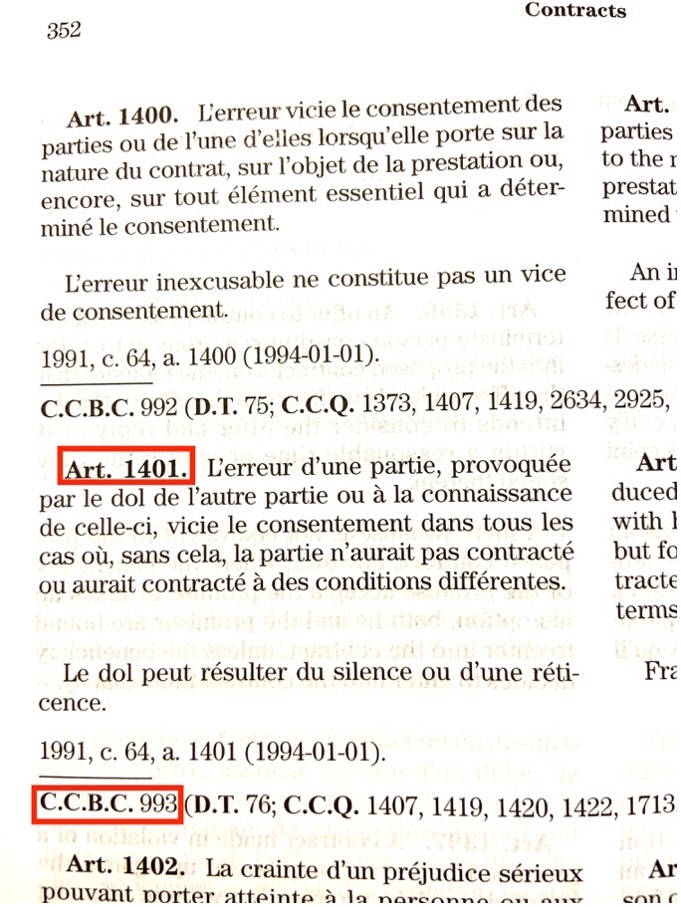

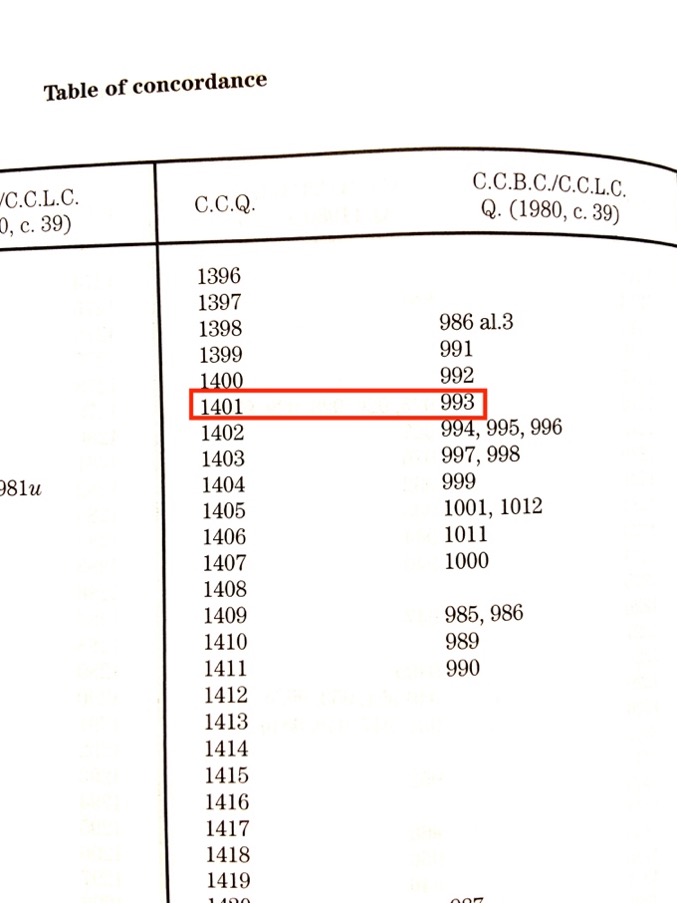

Une autre façon de trouver l’équivalence est d’aller voir l’édition Wilson-Lafleur du CcQ. En bas du texte de chaque article, l’article équivalent au CcBC est donné, s’il y en a un. Sinon, il y a aussi une table de concordance qui offre la concordance pour chaque article du CcQ.

Voici la même démarche à propos de l’art 1401 CcQ dans l’édition Wilson & Lafleur :

Veuillez noter que l’édition Yvon Blais n’offre pas la concordance en dessous du texte de chaque article du CcQ, et la table de concordance à la fin est classifiée selon l’ordre des articles du CcBC, ce qui rend la recherche un peu plus compliquée si notre point de départ est le CcQ.

Deuxième étape : trouvez l’article du CcBC dans La bibliothèque du Code civil

L’ouvrage auquel l’on fait référence est La bibliothèque du Code civil de la province de Québec par Charles-Chamilly de Lorimier et Charles-Albert Vilbon, qui est accessible dans son entièreté sur le site de la bibliothèque de McGill: https://www.library.mcgill.ca/hostedjournals/civilcode.html

Non, La bibliothèque du Code civil n’est pas une bibliothèque au sens propre, mais un ouvrage s’étendant sur plusieurs volumes contenant les autorités et les sources utilisées par les codificateurs pour chaque article du CcBC, allant des lois romaines en passant par les grands jurisconsultes français comme Du Moulin, Pothier, et plusieurs autres, terminant par les nouveaux codes, celui de Napoléon et celui de la Louisiane. Ainsi, cet ouvrage est une mine d’or servant de lien entre la tradition civiliste millénaire et le droit civil contemporain.

Pour vous faciliter la recherche à travers La bibliothèque du Code civil, voici une liste de tous les articles du CcBC contenus dans chacun des volumes de La bibliothèque :

• Vol 1 : 1–122

• Vol 2 : 123–307

• Vol 3 : 308–466

• Vol 4 : 467–565 (début)

• Vol 5 : 565 (suite)–718

• Vol 6 : 719–857

• Vol 7 : 858–1026

• Vol 8 : 1027–1149

• Vol 9 : 1150–1265

• Vol 10 : 1266–1384

• Vol 11 : 1385–1501

• Vol 12 : 1502–1603

• Vol 13 : 1604–1714

• Vol 14 : 1715–1809

• Vol 15 : 1810–1897

• Vol 16 : 1898–1975

• Vol 17 : 1976–2078

• Vol 18 : 2079–2196 (début)

• Vol 19 : 2196 (suite)–2233

• Vol 20 : 2234–2266

• Vol 21 : 2267–2277

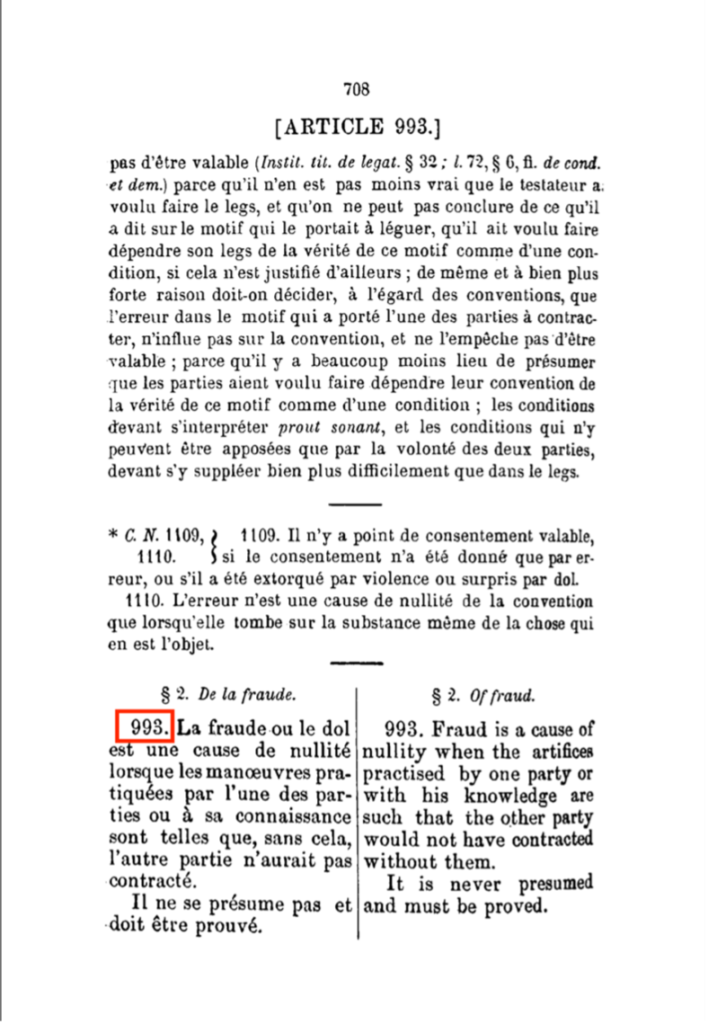

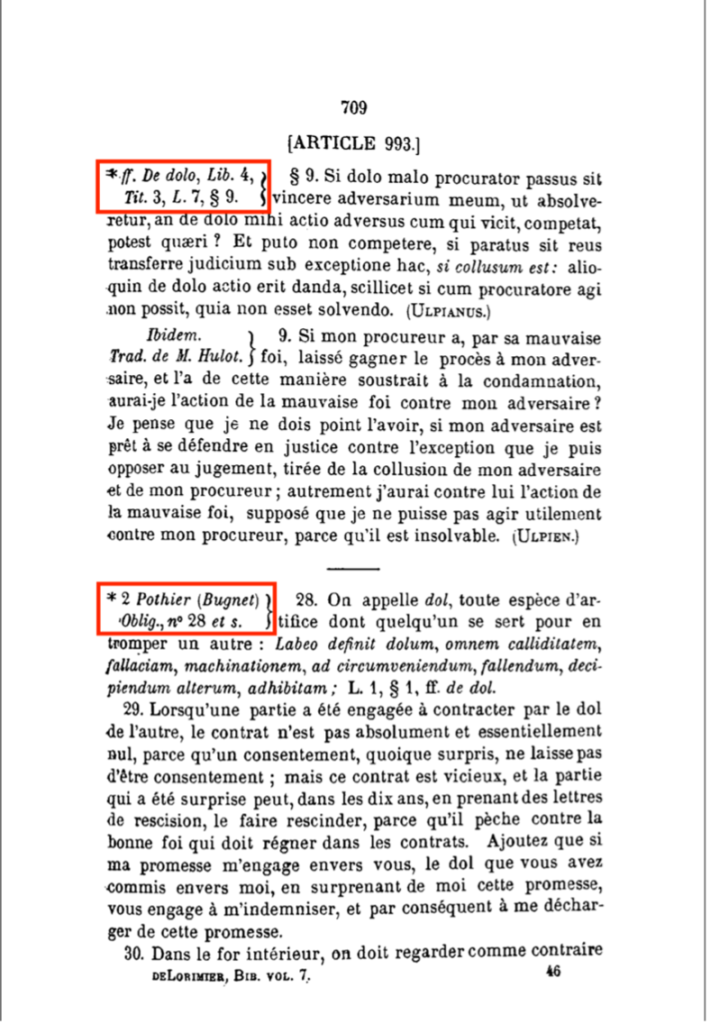

Dans l’exemple ci-dessous, nous essayons de trouver les sources de l’art 993 CcCB (l’équivalent de l’art 1401 CcQ) dans La bibliothèque. Grâce à la liste ci-haut, on voit que cet article se trouve analysé au volume 7.

Les deux premières pages à partir d’où l’art 993 CcBC est abordé nous offrent un extrait du Digeste de Justinien (le signe « ff » signifie Digeste) et un extrait de Pothier. Dans les pages suivantes, on peut lire d’autres extraits tirés de Domat et un article du Code Napoléon.

Des questions ? N’hésitez pas à nous contacter : law.library@mcgill.ca.

1Charles-Chamilly de Lorimier et Charles-Albert Vilbon, La bibliothèque du Code civil de la province de Quebec (ci-devant Bas-Canada) : ou recueil comprenant entre autres matières, Montréal : Cadieux & Dérome, 1871-90.