Guest post by Tabea Cornel, recipient of the 2017 Mary Louise Nickerson Award in Neuro History. Tabea Cornel is a PhD student in the Department of History and Sociology of Science at the University of Pennsylvania. Her dissertation focuses on handedness research within the brain and mind sciences in Europe and North America, particularly theories of the origin, prevalence, and pathological nature of left-handedness.

When asked about my dissertation topic as an early ABD (“all but dissertation”), I used to tell people that I work on the history of handedness research. A very common response was: “Handedness in what sense? Does it have something to do with molecules?” I usually explained that I’m researching manual preference, and that my project has nothing to do with chirality or any other fancy physical phenomenon.

After half a year of explaining what I mean by “handedness,” I came up with a more efficient strategy for answering the dissertation question. I started waving my hands in the air whenever I said “handedness.” This was somewhat effective. My conversation partners usually understood that I write a history of left- and right-handedness, but this also made them give me a look that said: “Oh my, what a boring thing to do.”

Having learned my lesson from these encounters, I now introduce the underlying argument of my research before I mention the actual topic. The extended version of my elevator pitch goes somewhat like this: My project investigates scientific classifications of human subpopulations. I particularly attend to the ways in which traditions, stereotypes, and social inequities inform research in the human sciences and the extent to which these conceptions produce “scientific” explanations for alleged human hierarchies.

Enter handedness: The lens through which I look at the phenomenon of hierarchical classifications is manual preference. This may seem an unexpected route to take, but research on handedness is a very fruitful avenue for tracing continuities within the human sciences in the past 150 years. More precisely, the project paints a picture of the longue durée of the mind, brain, and neuro-sciences. Since French anatomist and anthropologist P. Paul Broca (1824–1880) declared in 1865 that humans are right-handed because they are left-brained, researchers have used handedness as a proxy for the brain, mind, and character. On both sides of the Atlantic, scientists have linked anatomical, genetic, or hormonal explanations of the causes of handedness with age-old racist, sexist, and able-ist ideas of what makes one group of humans different from another one.

This framing gets many of my conversation partners (almost) as excited about my work as I am.

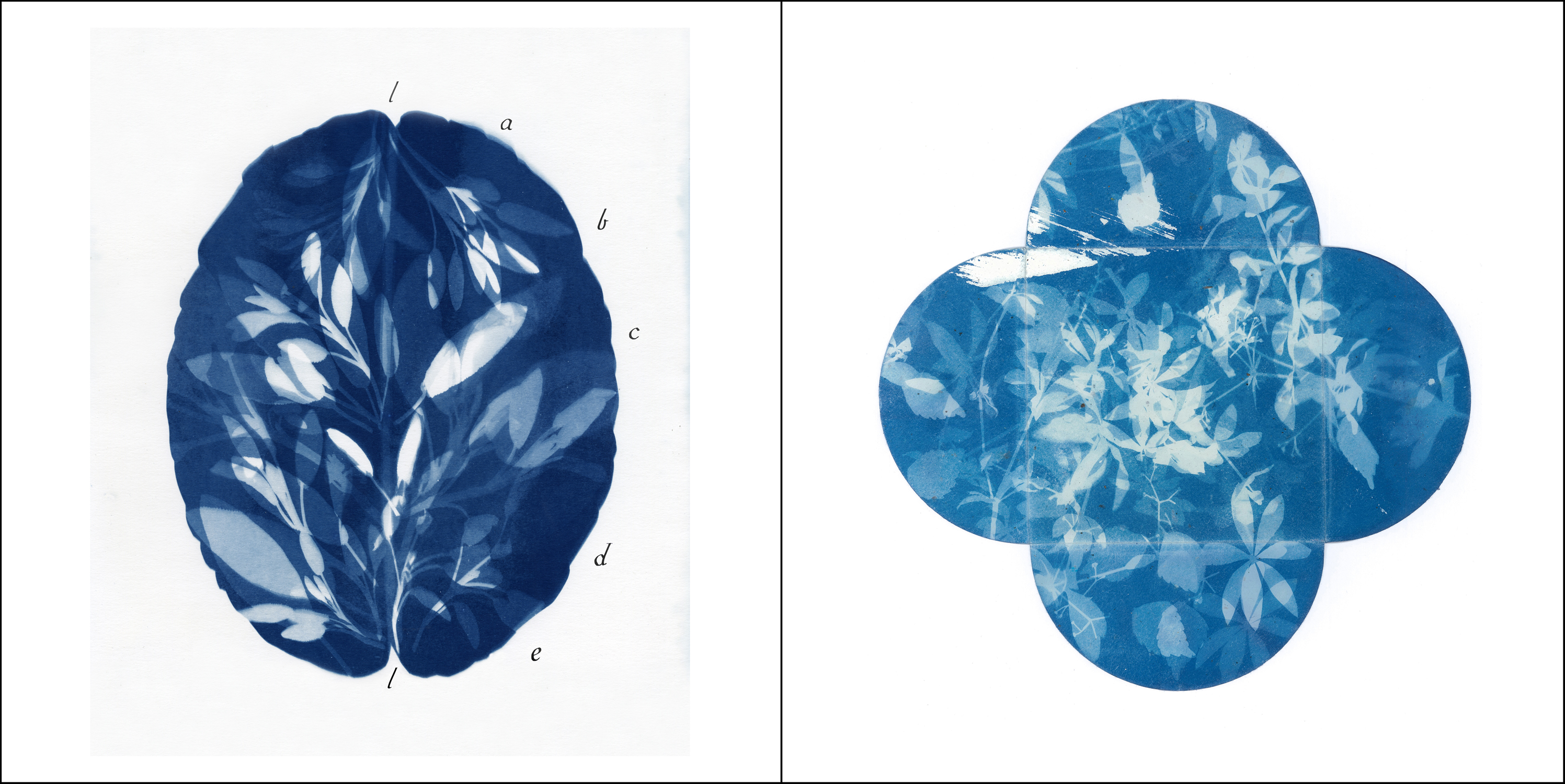

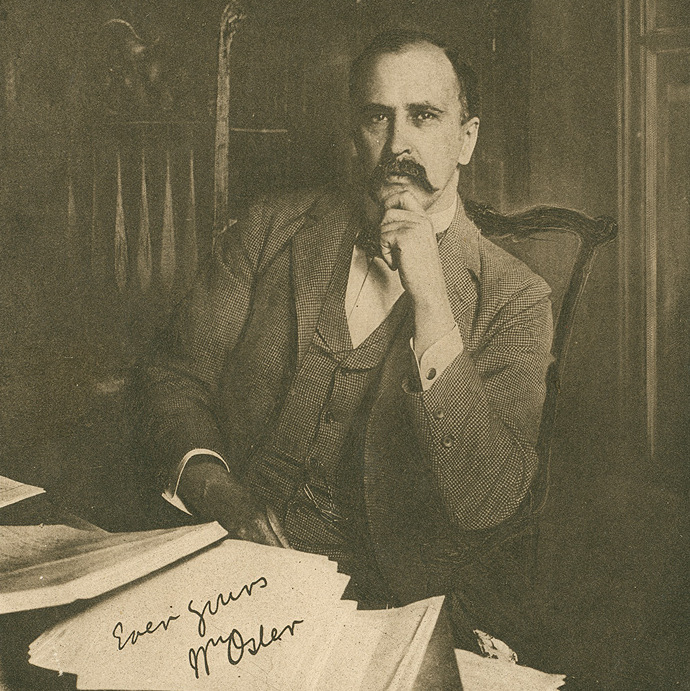

Several items at the Osler Library illustrate the distinct status of the hand even before 1865, when Broca advanced his theories about the connection between brain asymmetry and manual laterality. Scottish anatomist and neurologist Charles Bell’s (1774–1842) The Hand, for instance, provided a vivid portrait of the hand as an exclusively human organ. He wrote:

We ought to define the hand as belonging exclusively to man—corresponding in sensibility and motion with that ingenuity which converts the being who is the weakest in natural defence [sic], to the ruler over animate and inanimate nature.[1]

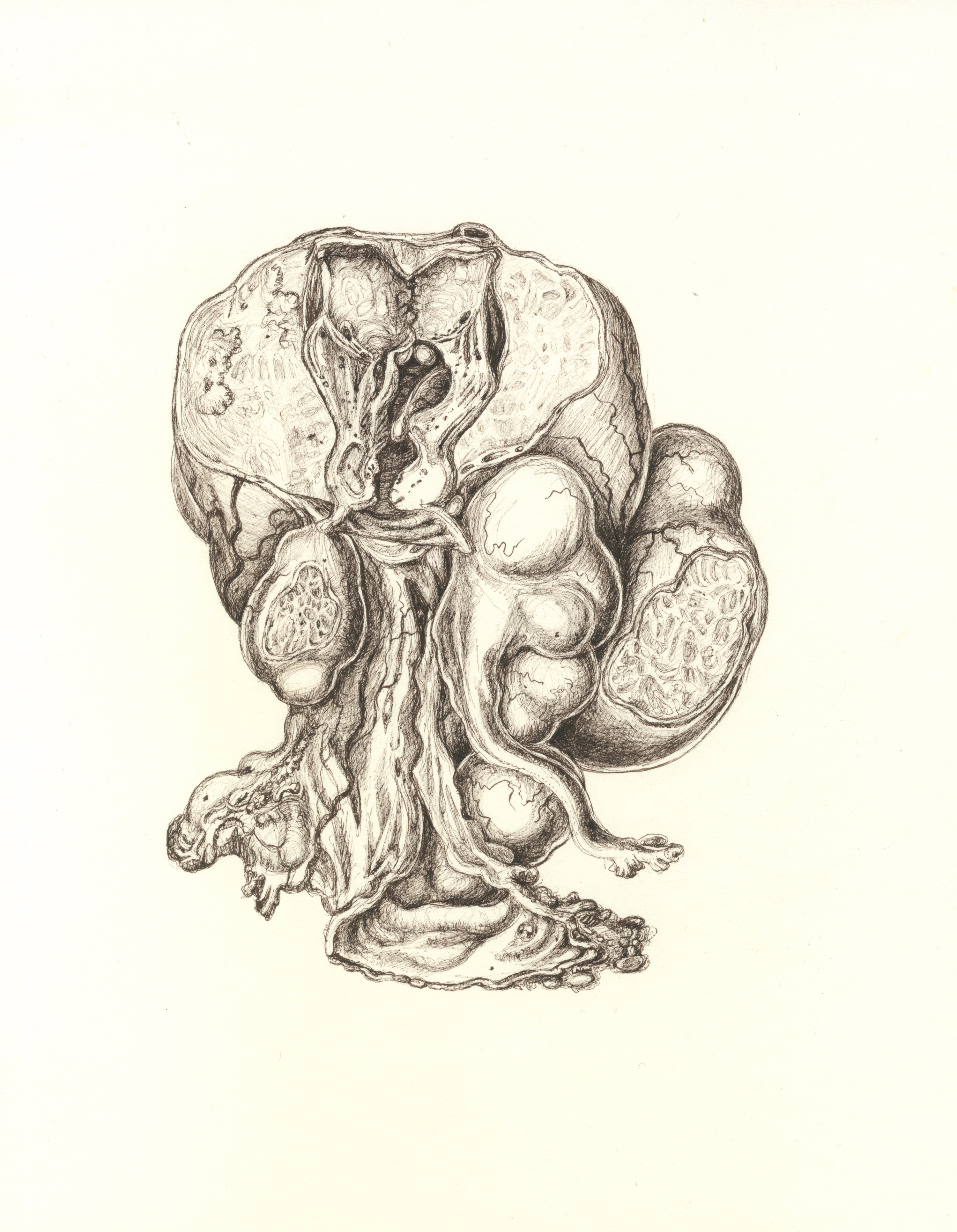

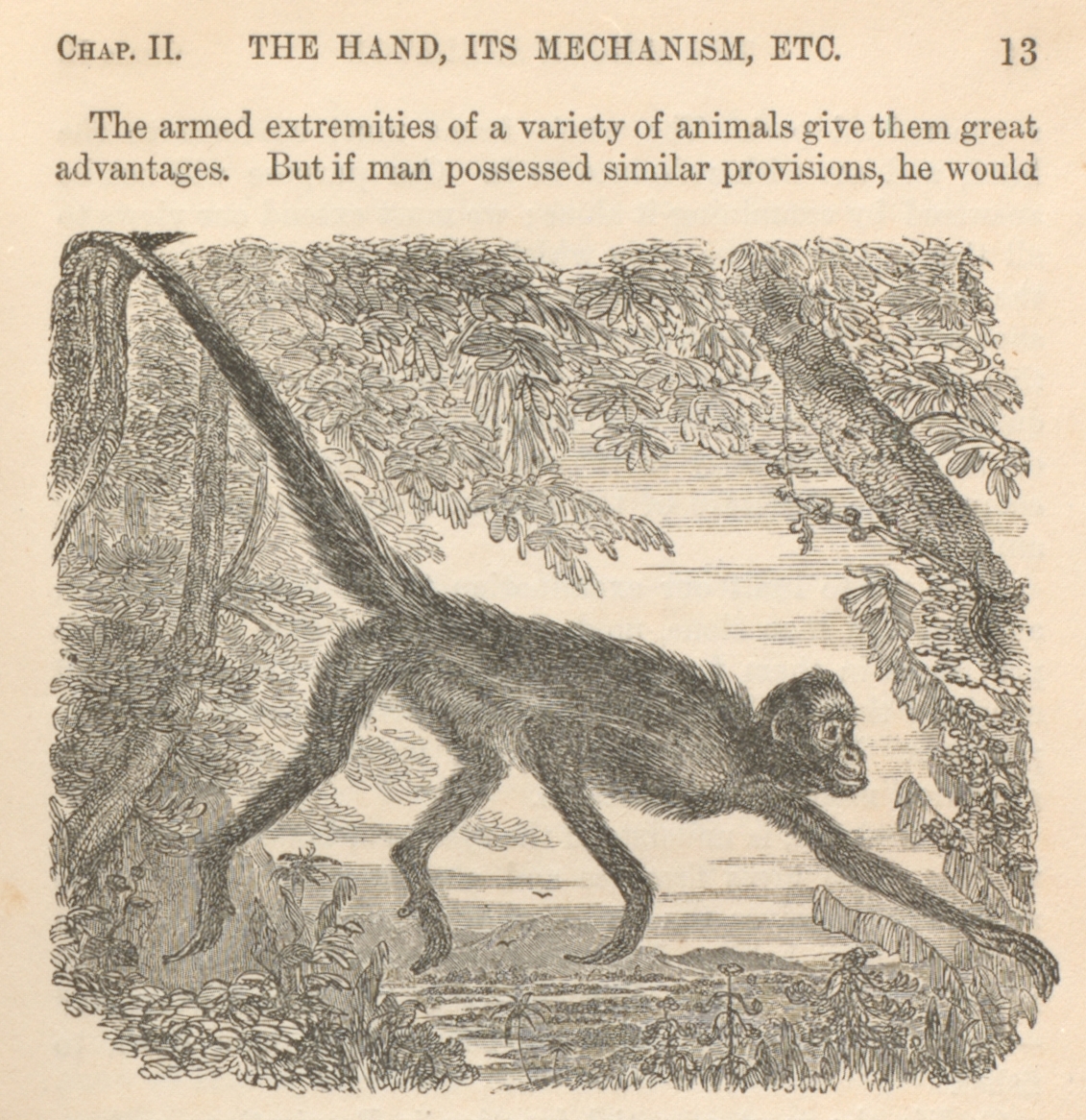

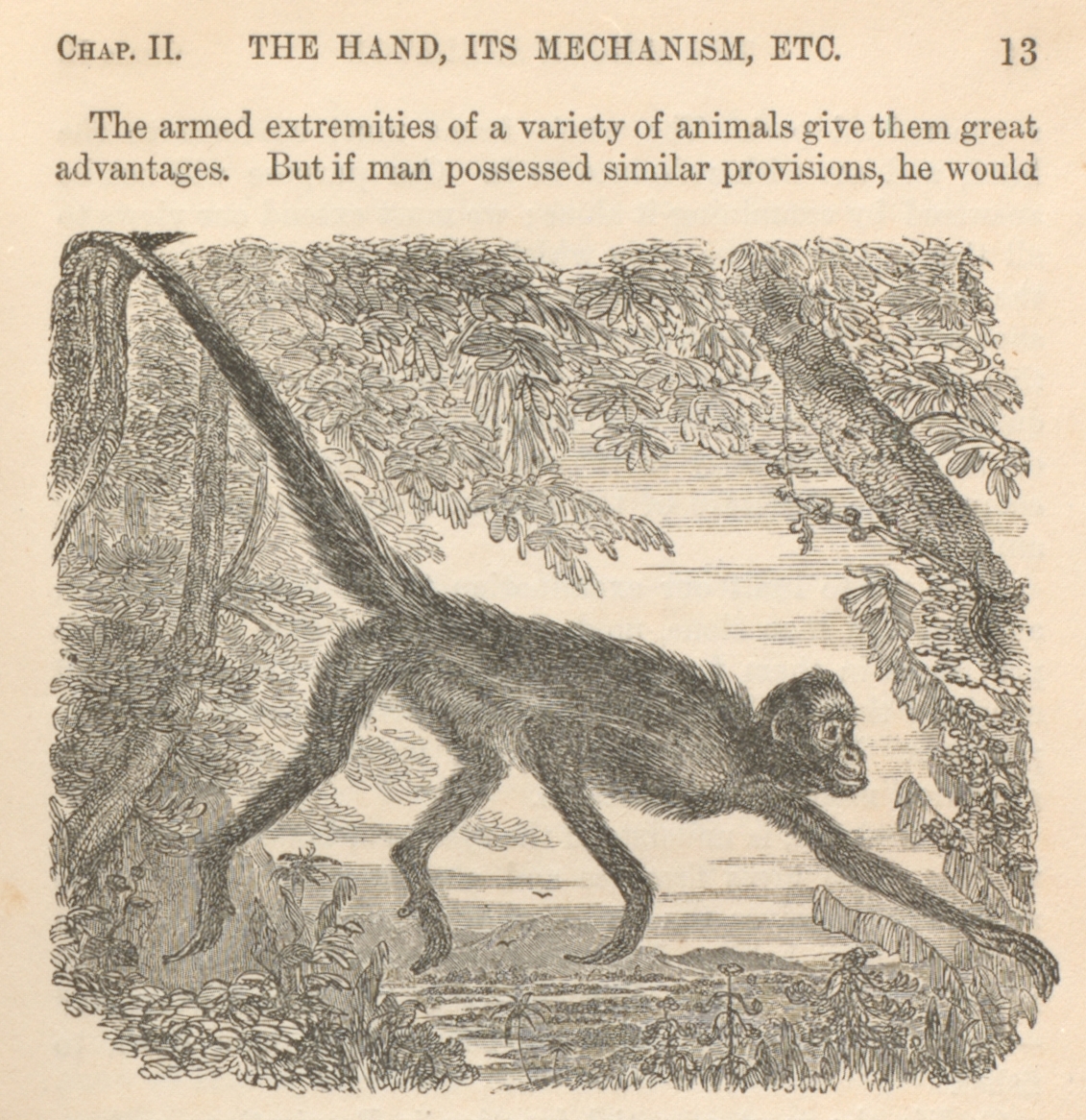

Bell was very clear about this instance of human exceptionality in the quoted edition from 1833. But for the 1865 edition, the publisher added a drawing on the page following this paragraph. It shows a monkey that is reaching for something outside of the image, probably a branch of a tree or a piece of fruit. Only in case it had not become entirely clear in the text, this drawing empowered the reader to visually grasp the difference between their own hand and the allegedly primitive paws of an ape.[2]

After having explained the system of bones, muscles, nerves, and blood vessels in intricate detail, Bell concluded that the hand, or the human body more generally, could not have developed accidentally. Bell clearly believed in a hierarchical divine creation, a “Great Chain of Being,” with white male humans all the way at the top.[3]

Bell’s faith in a purposeful design of the human species also underlay his argument that the superiority of the human hand derived not from its anatomical condition, but from its close association with the human intellect:

In discussing this subject of the progressive improvement of organized beings, it is affirmed that the last created of all, man, is not superior in organization to the others, and that if deprived of intellectual power he is inferior to the brutes. … Man is superior in organization to the brutes,—superior in strength—in that constitutional property which enables him to fulfil his destinies by extending his race in every climate, and living on every variety of nutriment. Gather together the most powerful brutes, from the artic [sic] circle or torrid zone, to some central point—they will die, diseases will be generated, and will destroy them. With respect to the superiority of man being in his mind, and not merely in the provisions of his body, it is no doubt true;—but as we proceed, we shall find how the Hand supplies all instruments, and by its correspondence with the intellect gives him universal dominion.[4]

A further drawing was added to the 1865 edition in the interest of enforcing said hierarchies amongst different human groups even more. The reader looks at a scantily dressed dark-skinned male with a dagger hanging from his neck. This person is crawling on the floor under a white male’s bed and reaches for valuables on the night stand.[5]

The fact that the aforementioned monkey and the apparent thief reach for something with their left hands implicitly reiterates the inferiority of these two creatures. Other illustrations in the 1865 volume present right-handed actions, no matter if they display the function of bones and muscles or more complete (parts of) light-skinned humans.

The fact that the aforementioned monkey and the apparent thief reach for something with their left hands implicitly reiterates the inferiority of these two creatures. Other illustrations in the 1865 volume present right-handed actions, no matter if they display the function of bones and muscles or more complete (parts of) light-skinned humans.

Because of the presumed close association between the hand and the mind, the moral valency of actions of the hand implied a hierarchy of individual beings and groups of beings. The idea of the “Great Chain of Being” is mirrored in the grasping of the left monkey paw, the attempted theft of the black left hand, and all other ostensibly decent and accomplished uses of white right hands shown in further illustrations in the volume.

The English physiologist and anatomist George M. Humphry (1820–1896) echoed the close association between the mind and the hand in his treatise on The Human Foot and the Human Hand. He insisted that “The Hand [Is] the Organ of the Will” and that “the hand becomes an organ of expression and an index of character” because the mind works through the hand.[6]

Other sources at the Osler Library bear witness of much more heterodox approaches to the mind as a window into human character. Take the 78-page monograph The Hand Phrenologically Considered. The anonymous author provided a manual for how to perform a phrenological reading of a person’s hands to determine their character, abilities, and experiences. (The traditional phrenological approach would have been to palpate an individual’s skull.)

Other sources at the Osler Library bear witness of much more heterodox approaches to the mind as a window into human character. Take the 78-page monograph The Hand Phrenologically Considered. The anonymous author provided a manual for how to perform a phrenological reading of a person’s hands to determine their character, abilities, and experiences. (The traditional phrenological approach would have been to palpate an individual’s skull.)

In line with my argument that practitioners used the hand to advance theories about the character, mind, and brain of human subpopulations, the author of The Hand Phrenologically Considered suggested that the “Form of Extremities Differs in Individuals of the Same Species” by age, sex, race, class, and ethnicity.[7]

In a similar vein, the Carter Medicine Company employed the promise of phrenological assessments of the hand in the interest of financial gain. In a little pamphlet, Mysteries of Our Hands and Faces, Carter Medicine provided instructions for the phrenological reading of hands as well as parts of the face (forehead, eyes, nose, etc.). The Company offered these instructions in conjunction with directions for how to use their liver pills most effectively.

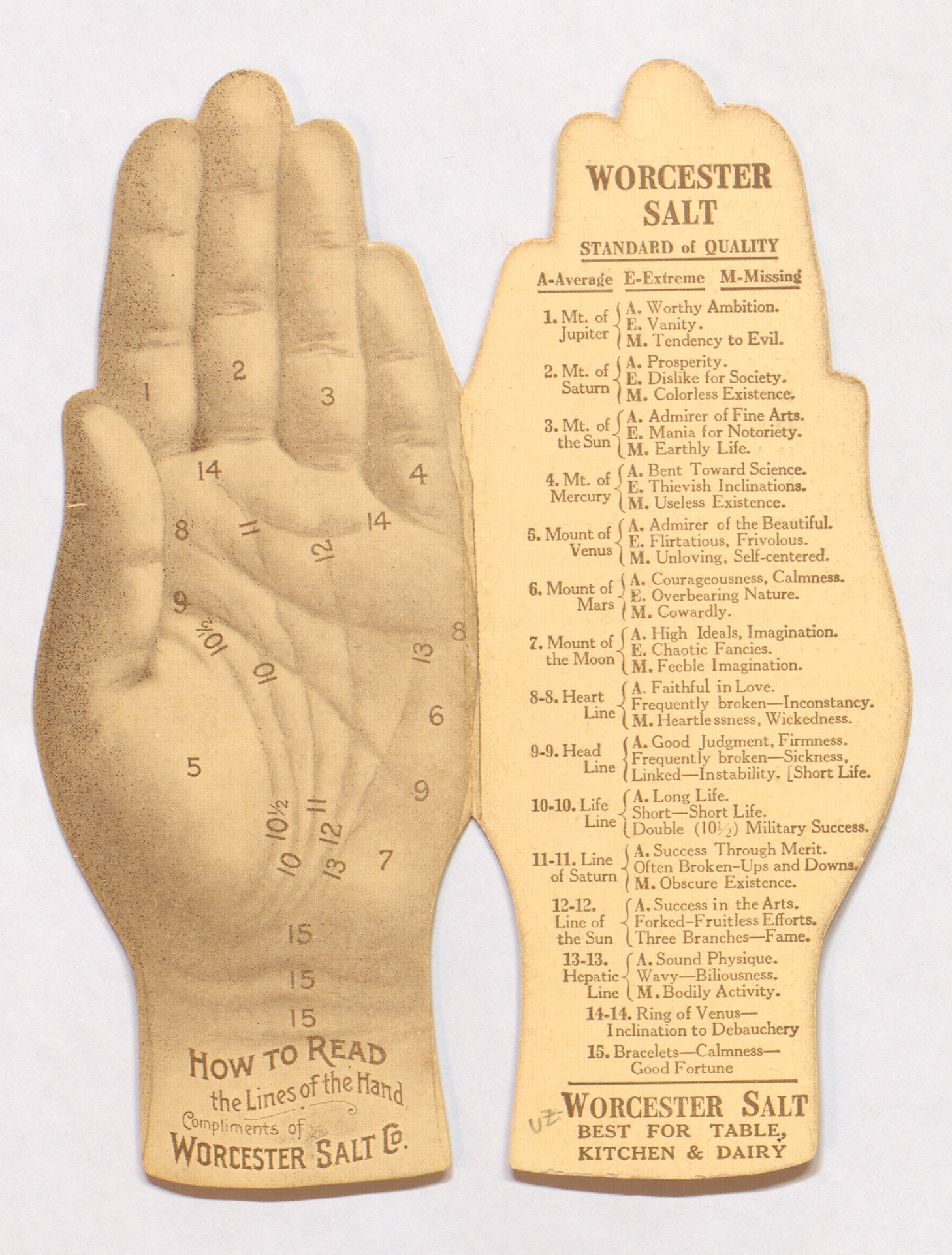

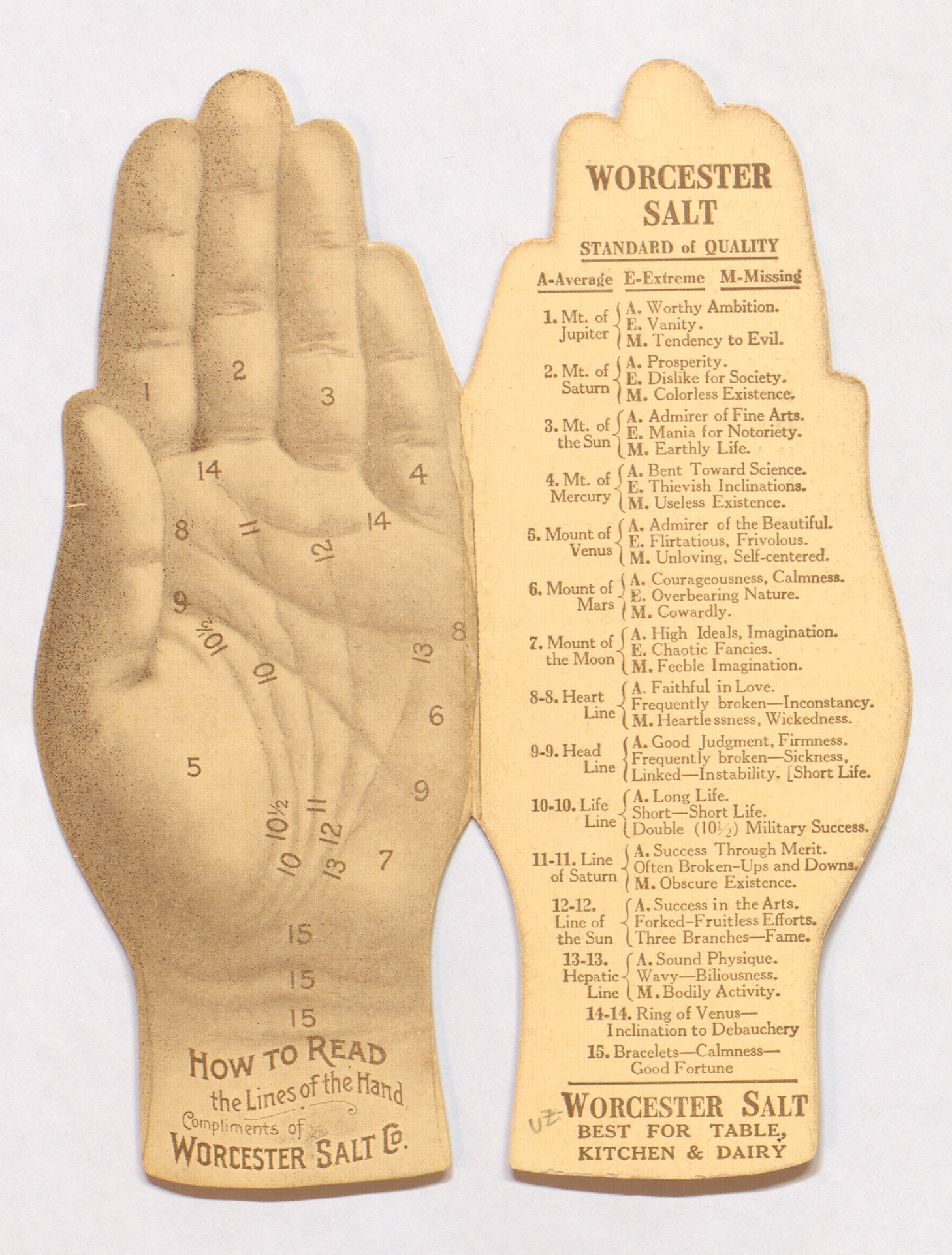

Even more eclectic is a little hand-shaped advertisement for the Worcester Salt Company. Under the slogan “Your fortune is in your own hands,” the pamphlet offered a short introduction into palmistry to all potential buyers of Worcester Salt.[8] The advertisement makes intelligible the wide-spread fascination for heterodox sciences that connected the mind and the hand in the late 19th century, decades after Broca had advanced his anatomical theory.

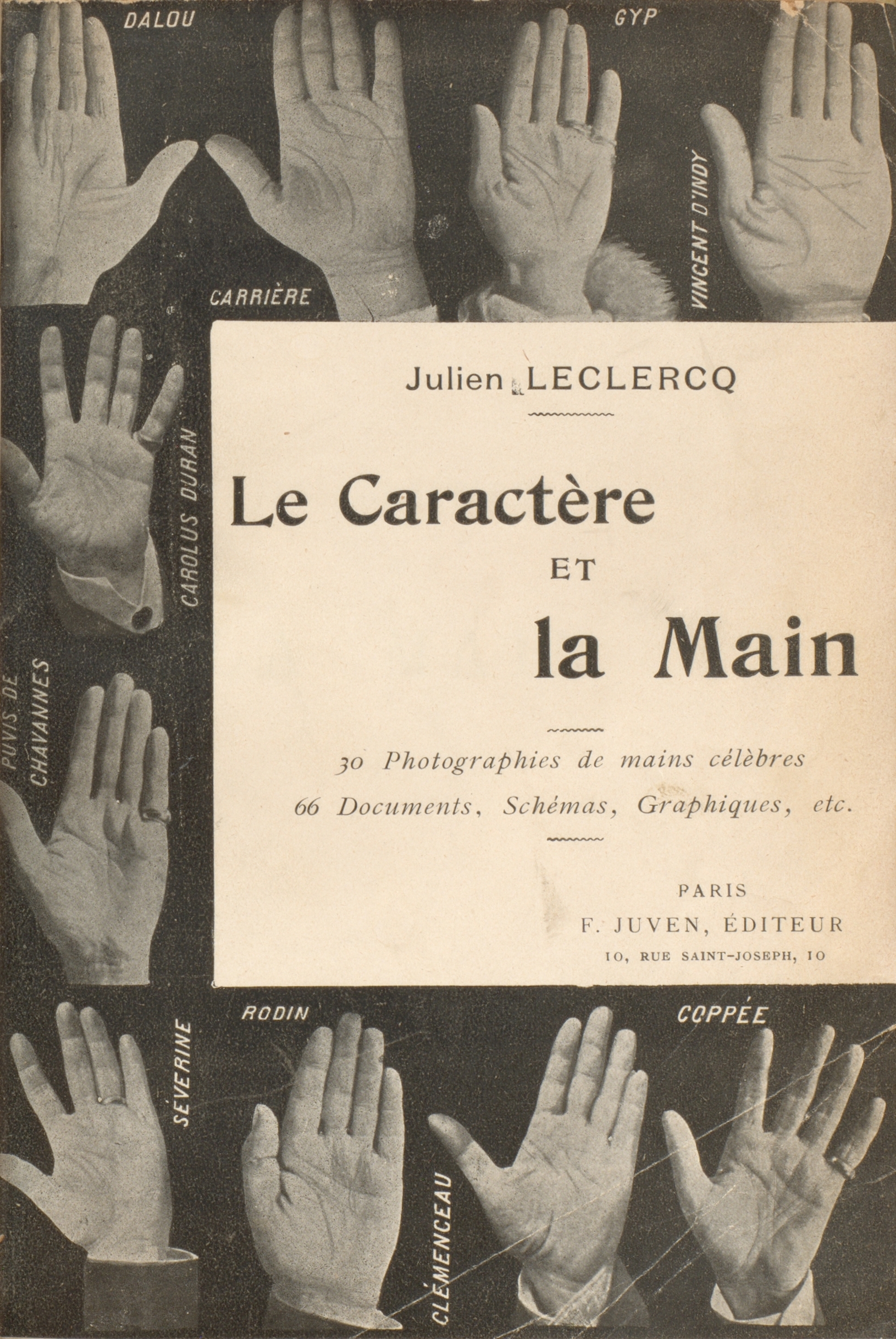

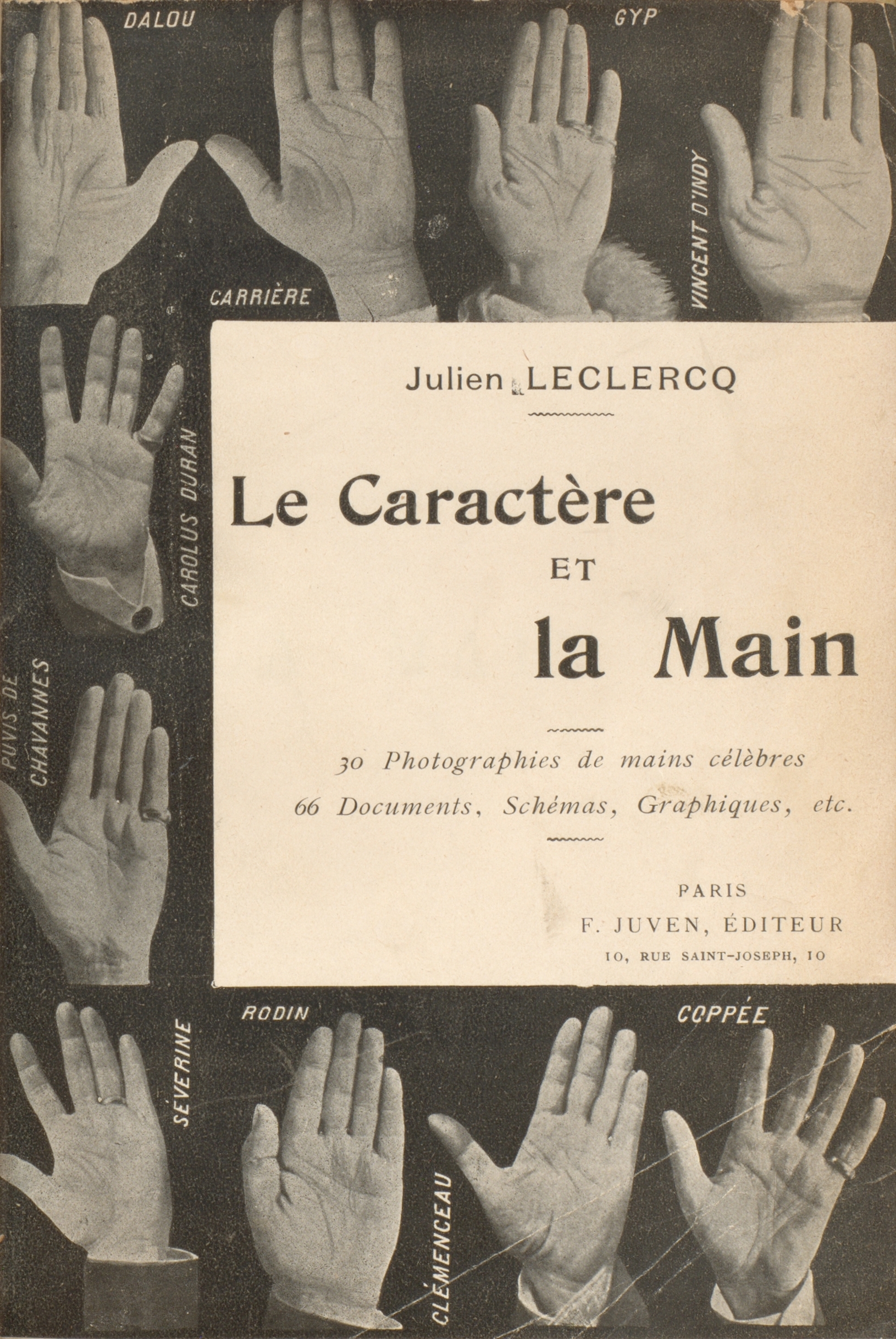

Other examples of holdings at the Osler Library that put the hand into the focus of human classification practices abound. The French poet Joseph L.J. Leclercq (1865–1901), for instance, published a historically-oriented work about palmistry. Concretely, he provided examples for and distinguished between “[c]hirologie, chirographie[,] chirognonomie,” “chiroscopie, chirosophie, palmisophie, [and] chiropsie.”[9] Who knew that there were so many different approaches to turning the hand into a proxy for the mind?

Other examples of holdings at the Osler Library that put the hand into the focus of human classification practices abound. The French poet Joseph L.J. Leclercq (1865–1901), for instance, published a historically-oriented work about palmistry. Concretely, he provided examples for and distinguished between “[c]hirologie, chirographie[,] chirognonomie,” “chiroscopie, chirosophie, palmisophie, [and] chiropsie.”[9] Who knew that there were so many different approaches to turning the hand into a proxy for the mind?

Last but not least, I want to mention Hungarian writer Pál Tábori’s (1908–1974) much more recent monograph The Book of the Hand. Tábori, who had a deep interest in psychical phenomena, connected in his work palmistry with idioms and superstitions about the hand, as well as with considerations of manual gestures, the sense of touch, dactyloscopy (the reading of fingerprints), handwriting and graphology, and the condition of having lost a hand and/or using an artificial hand.[10]

Last but not least, I want to mention Hungarian writer Pál Tábori’s (1908–1974) much more recent monograph The Book of the Hand. Tábori, who had a deep interest in psychical phenomena, connected in his work palmistry with idioms and superstitions about the hand, as well as with considerations of manual gestures, the sense of touch, dactyloscopy (the reading of fingerprints), handwriting and graphology, and the condition of having lost a hand and/or using an artificial hand.[10]

Tábori’s work intrigues by its sheer breadth of hand-related phenomena, some of which we would consider apt research topics for establishment science, and others that are clearly heterodox. As I learned during my four weeks at the Osler Library, the desire to access the hidden brain through the manifest hand brought these approaches together.

[1] Charles Bell, The Hand: Its Mechanism and Vital Endowments, as Evincing Design, Bridgewater Treatises on the Power, Wisdom, and Goodness of God as Manifested in the Creation 4 (Philadelphia: Carey, Lea & Blanchard, 1833), 26.

[2] Charles Bell, The Hand: Its Mechanism and Vital Endowments, as Evincing Design, 7th ed., Bridgewater Treatises on the Power, Wisdom, and Goodness of God as Manifested in the Creation 4 (London: Bell & Daldy, 1865), 13.

[3] Arthur O. Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2009).

[4] Bell, The Hand, 39–40.

[5] Bell, The Hand, 29.

[6] George Murray Humphry, The Human Foot and the Human Hand (Cambridge: Macmillan and Co., 1861), 156–61.

[7] N.N., The Hand Phrenologically Considered: Being a Glimpse at the Relation of the Mind with the Organisation of the Body (London: Chapman and Hall, 1848), 51–57.

[8] Worcester Salt Company, “How to Read the Lines of the Hand” (New York, 1894).

[9] Joseph Louis Julien Leclercq, Le caractère et la main: Histoire et documents (Paris: F. Juven, [1900]), 1–2.

[10] Pál Tábori, The Book of the Hand: A Compendium of Fact and Legend Since the Dawn of History (Philadelphia: Chilton Company, 1962).

The fact that the aforementioned monkey and the apparent thief reach for something with their left hands implicitly reiterates the inferiority of these two creatures. Other illustrations in the 1865 volume present right-handed actions, no matter if they display the function of bones and muscles or more complete (parts of) light-skinned humans.

The fact that the aforementioned monkey and the apparent thief reach for something with their left hands implicitly reiterates the inferiority of these two creatures. Other illustrations in the 1865 volume present right-handed actions, no matter if they display the function of bones and muscles or more complete (parts of) light-skinned humans. Other sources at the Osler Library bear witness of much more heterodox approaches to the mind as a window into human character. Take the 78-page monograph The Hand Phrenologically Considered. The anonymous author provided a manual for how to perform a phrenological reading of a person’s hands to determine their character, abilities, and experiences. (The traditional phrenological approach would have been to palpate an individual’s skull.)

Other sources at the Osler Library bear witness of much more heterodox approaches to the mind as a window into human character. Take the 78-page monograph The Hand Phrenologically Considered. The anonymous author provided a manual for how to perform a phrenological reading of a person’s hands to determine their character, abilities, and experiences. (The traditional phrenological approach would have been to palpate an individual’s skull.) Other examples of holdings at the Osler Library that put the hand into the focus of human classification practices abound. The French poet Joseph L.J. Leclercq (1865–1901), for instance, published a historically-oriented work about palmistry. Concretely, he provided examples for and distinguished between “[c]hirologie, chirographie[,] chirognonomie,” “chiroscopie, chirosophie, palmisophie, [and] chiropsie.”

Other examples of holdings at the Osler Library that put the hand into the focus of human classification practices abound. The French poet Joseph L.J. Leclercq (1865–1901), for instance, published a historically-oriented work about palmistry. Concretely, he provided examples for and distinguished between “[c]hirologie, chirographie[,] chirognonomie,” “chiroscopie, chirosophie, palmisophie, [and] chiropsie.” Last but not least, I want to mention Hungarian writer Pál Tábori’s (1908–1974) much more recent monograph The Book of the Hand. Tábori, who had a deep interest in psychical phenomena, connected in his work palmistry with idioms and superstitions about the hand, as well as with considerations of manual gestures, the sense of touch, dactyloscopy (the reading of fingerprints), handwriting and graphology, and the condition of having lost a hand and/or using an artificial hand.

Last but not least, I want to mention Hungarian writer Pál Tábori’s (1908–1974) much more recent monograph The Book of the Hand. Tábori, who had a deep interest in psychical phenomena, connected in his work palmistry with idioms and superstitions about the hand, as well as with considerations of manual gestures, the sense of touch, dactyloscopy (the reading of fingerprints), handwriting and graphology, and the condition of having lost a hand and/or using an artificial hand.