Au 17e siècle, le Brésil est une terre portugaise depuis sa découverte en 1500 par le navigateur Pedro Álvares Cabral. Toutefois, une enclave hollandaise existe entre 1624 et 1654 au nord-est du Brésil. C’est dans ce contexte que deux hollandais, le médecin Willem Piso et l’astronome Georg Marggrav, accompagnent en 1638 le prince de Nassau dans son voyage au Brésil. C’est l’occasion pour les deux savants d’explorer le territoire et d’en répertorier la faune et la flore.

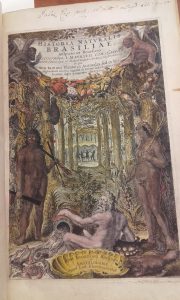

Leurs découvertes sont rassemblées en 1648 par le géographe Johannes De Laet dans un livre intitulé Historia naturalis Brasiliae. Cet ouvrage est considéré comme le premier traité scientifique sur le Brésil. La bibliothèque Osler possède un exemplaire de l’édition originale (Osler room – folio P678h 1648), imprimée à Leyde, par la célèbre maison Elzevier. Le titre-frontispice est particulièrement travaillé : il s’agit d’une gravure colorée à la main, qui semble évoquer le Brésil comme un nouveau Paradis. On y voit deux indigènes, dans une végétation luxuriante, entourés de nombreux animaux (perroquets, singes, fourmiliers, serpents, poissons, crabes, tortues, paresseux…).

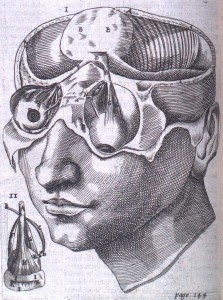

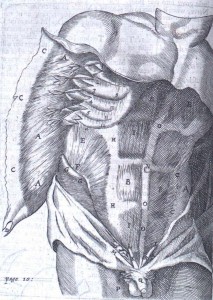

Le livre se compose de deux parties : le De medicina Brasiliensi écrit par Willem Piso, et l’Historia rerum naturalium Brasiliae de Georg Marggrav. L’ensemble, organisé et complété par Johannes De Laet, est richement illustré par plus de quatre cents gravures sur bois.

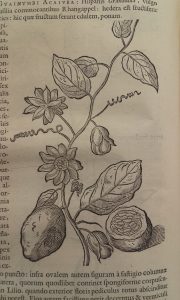

Dans son De medicina Brasiliensi, Willem Piso recense les maladies et les venins qui existent au Brésil, ainsi que leurs remèdes locaux. Il y décrit également les vertus thérapeutiques des plantes (De facultatibus simplicium). On trouve d’ailleurs une explication très intéressante de la fabrication du sucre de canne (De saccharo).

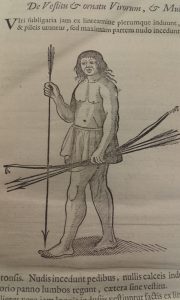

La seconde partie, l’Historia rerum naturalium Brasiliae, rédigée par Georg Marggrav, recense les plantes, les poissons, les animaux et les insectes du Brésil. Une rapide description du pays et de ses habitants est également incluse : Marggrav y évoque les coutumes des indigènes du Brésil (vêtements, religion, nourriture… et même la langue avec un bref lexique incorporé dans le texte).

L’Historia naturalis Brasiliae a fait connaître en Europe de nouvelles plantes médicinales (comme l’ipecacuanha, utilisée notamment pour traiter la dysenterie). Il est devenu un ouvrage de référence pour les naturalistes européens tout au long des 17e et 18e siècles: son influence est notamment perceptible dans les travaux de Buffon et de Linné. C’est un riche témoignage des tentatives de description et de compréhension de la nature au 17e siècle.

Bibliographie:

Brienen R. P., Visions of Savage Paradise: Albert Eckhout, Court Painter in Colonial Dutch Brazil, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 2006.

Charlot C, Guibert M.-S., “Petite histoire de la Racine Brésilienne en France au 17ème siècle”, 38e Congrès international d’histoire de la Pharmacie, Séville, 19-22 septembre 2007, disponible en ligne.

Galloway J. H., “Tradition and innovation in the American sugar Industry, c. 1500- 1800: an explanation”, Annals of the Association of American geographers, 75, 3, 1985.

Medeiros M. F. T., Albuquerque U. P., “Abstract food flora in 17th century northeast region of Brazil in Historia Naturalis Brasiliae”, Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 10, 50, 2014.

Safier N., “Beyond Brazilian nature: the editorial itineraries of Marcgraf and Piso’s Historia Naturalis Brasiliae”, dans Van Groesen M. (ed.), The Legacy of Dutch Brazil, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Walker T. D., “The medicines trade in the Portuguese Atlantic world: acquisition and dissemination of healing knowledge from Brazil (c. 1580–1800)”, Social history of medicine, 26, 3, 2013.

Whitehead P. J. P., Boeseman M., A portrait of Dutch 17th century Brazil : animals, plants, and people by the artists of Johan Maurits of Nassau, Amsterdam – Oxford – New-York, North-Holland Publishing Company, 1989.