Sylie Boisjoli and Shana Cooperstein are doctoral students in art history in the Department of Art History and Communication Studies at McGill. They are the guest curators of our current exhibition, On the Surface/Skin Deep. They agreed to answer a couple questions about the exhibition and their work.

Sylie Boisjoli and Shana Cooperstein are doctoral students in art history in the Department of Art History and Communication Studies at McGill. They are the guest curators of our current exhibition, On the Surface/Skin Deep. They agreed to answer a couple questions about the exhibition and their work.

AD: First, could you each tell me a little bit about your research interests, and current work?

SB: I’m currently working on my PhD thesis in the Department of Art History and Communication Studies and am the course supervisor for the Museum Internship class, which aims to accompany and enhance students’ internships at museums or galleries. During my MA in art history, which I also did at McGill, I conducted extensive primary research at the Osler Library for my major research paper on late nineteenth-century French artists’ visualisations of the development of serum therapy treatments against diphtheria. My PhD work has now shifted to investigate the emergence of the notion of prehistoric time in France within wider nineteenth-century scientific and philosophical debates around Darwinian evolutionary theories on the progress and mutability of the human species. By examining the social, political, and intellectual conditions in which the idea of prehistory developed, I analyze how representations of prehistoric people and places normalized the belief that time was a dynamic force that could drive forward or limit France’s progress as a nation. My work thus explores the increased public interest in representations and conceptions of prehistoric time in relation to the wider nineteenth-century impulse for reading the past and the passage of time in/on the body. My dissertation also considers the notion of prehistory as an indicator of, and participant in, a significant shift in how French society understood its national history. The fascination with prehistory was certainly not restricted to a few specialists in the human sciences. Instead, my research investigates ways in which artists, writers, and scientists disseminated their visions of the past across the French public sphere.

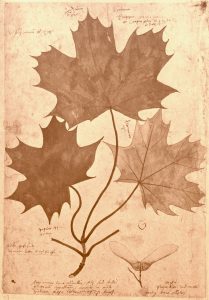

SC: After receiving a Master of Arts in art history at Temple University, I began pursuing a doctorate in art history at McGill University. My personal trajectory has led me to develop an interest in theories of representation, standardization, and the intersection of art and science. Bridging these areas of inquiry, my dissertation situates nineteenth-century French drawing pedagogy at the nexus of art, industrial design and the theories of knowledge. Specifically, I explore the institutionalization and reorganization of drawing in public pedagogical programs, design schools, and at the École des Beaux-Arts. In the past, I have had the opportunity to intern at various institutions, such as The Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, The Museum of Modern Art, and The Carnegie Museum of Art. I also have authored an article in Leonardo titled: “Imagery and Astronomy: The Visual Antecedents Informing Non-Reproductive Depictions of the Orion Nebula.”

AD: What led you to choose the topic of the exhibition? How did you go about exploring the topic and selecting materials?

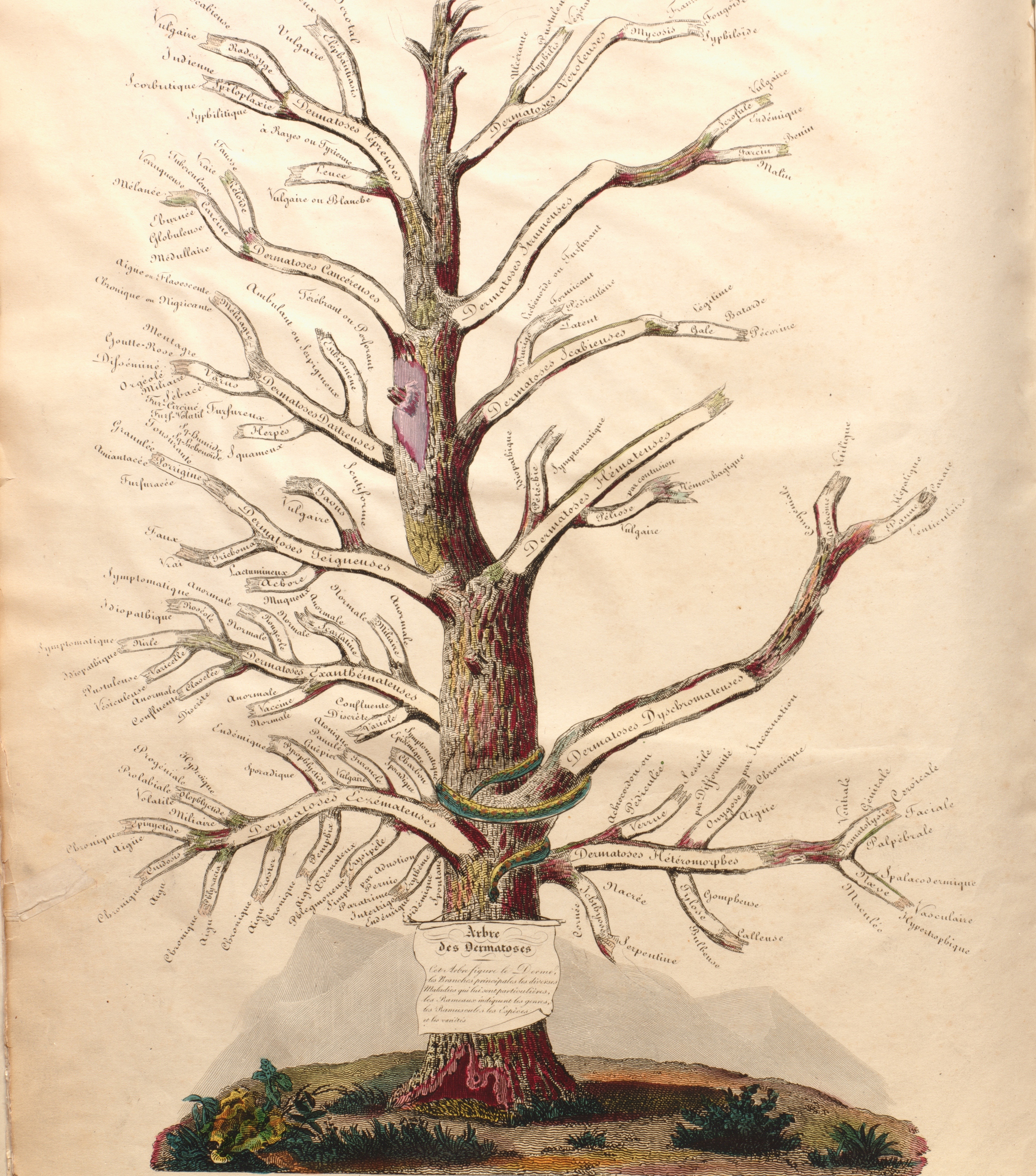

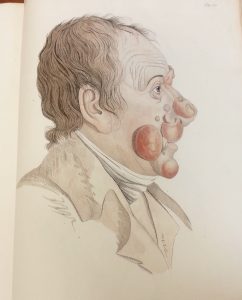

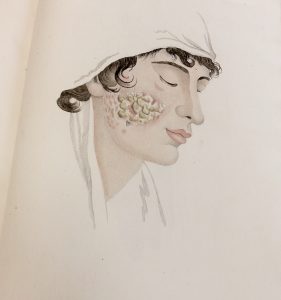

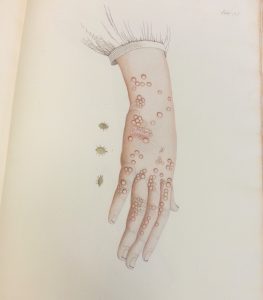

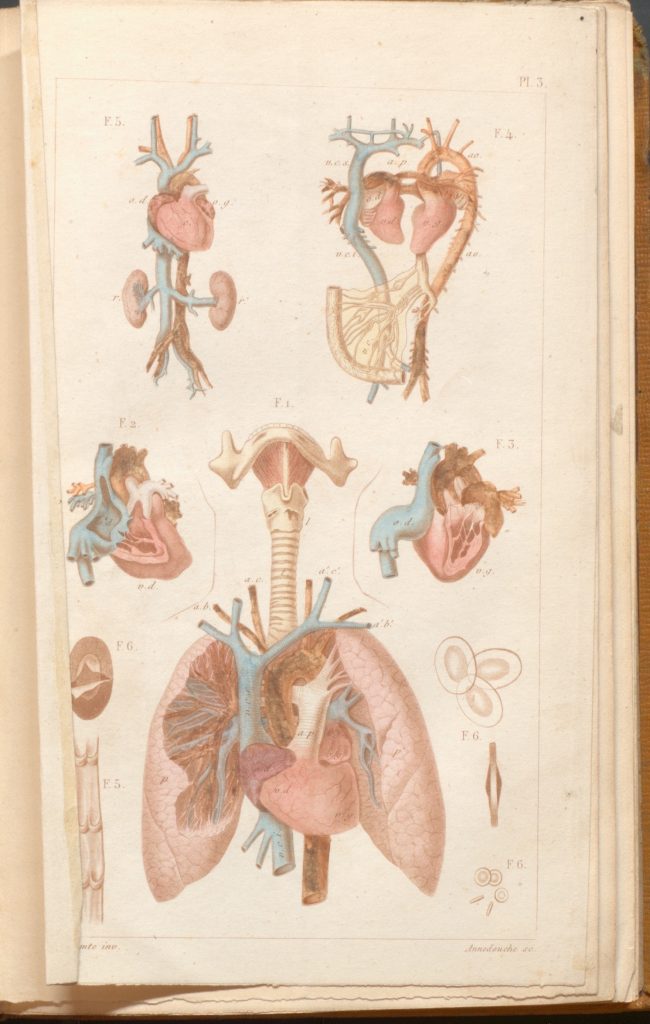

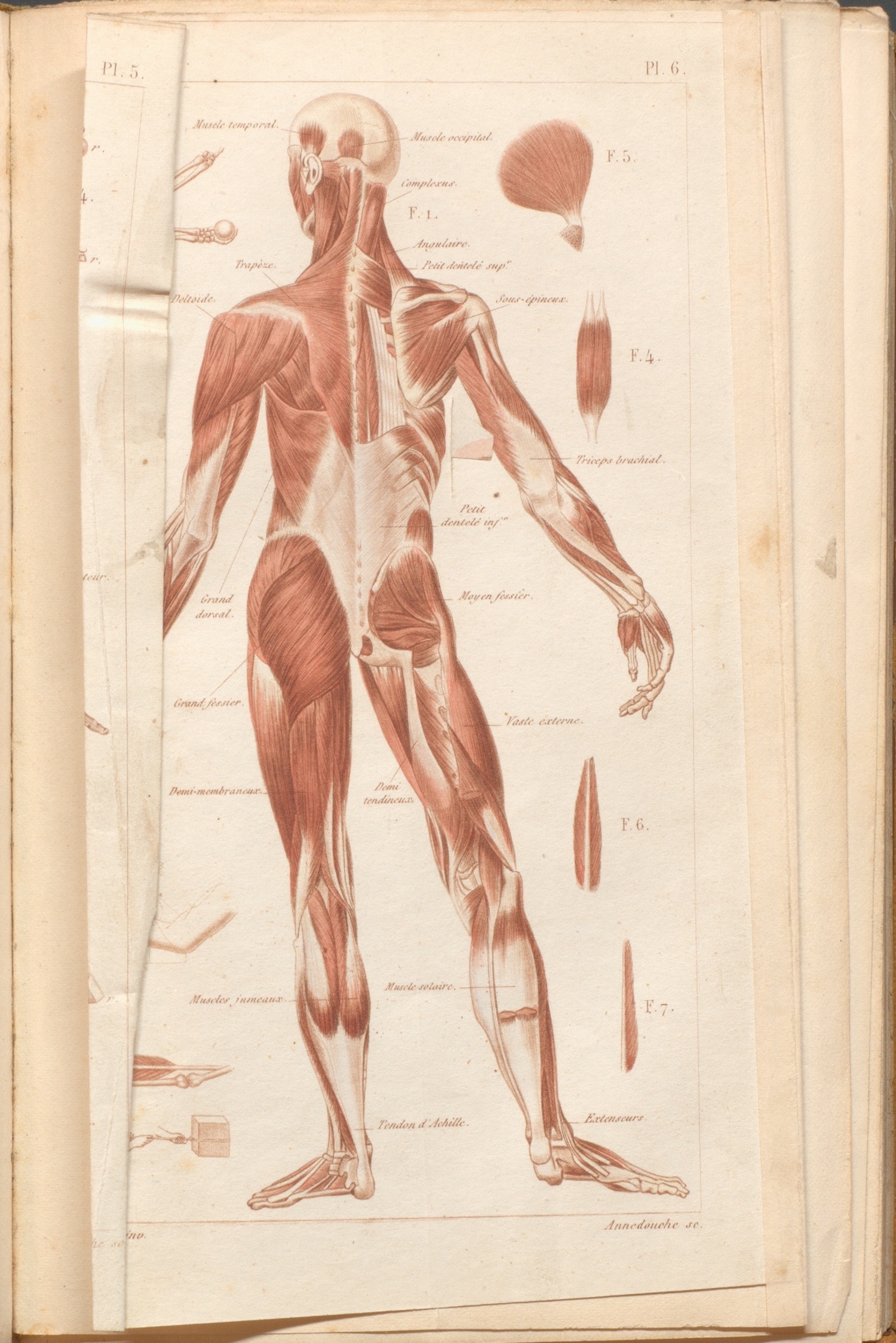

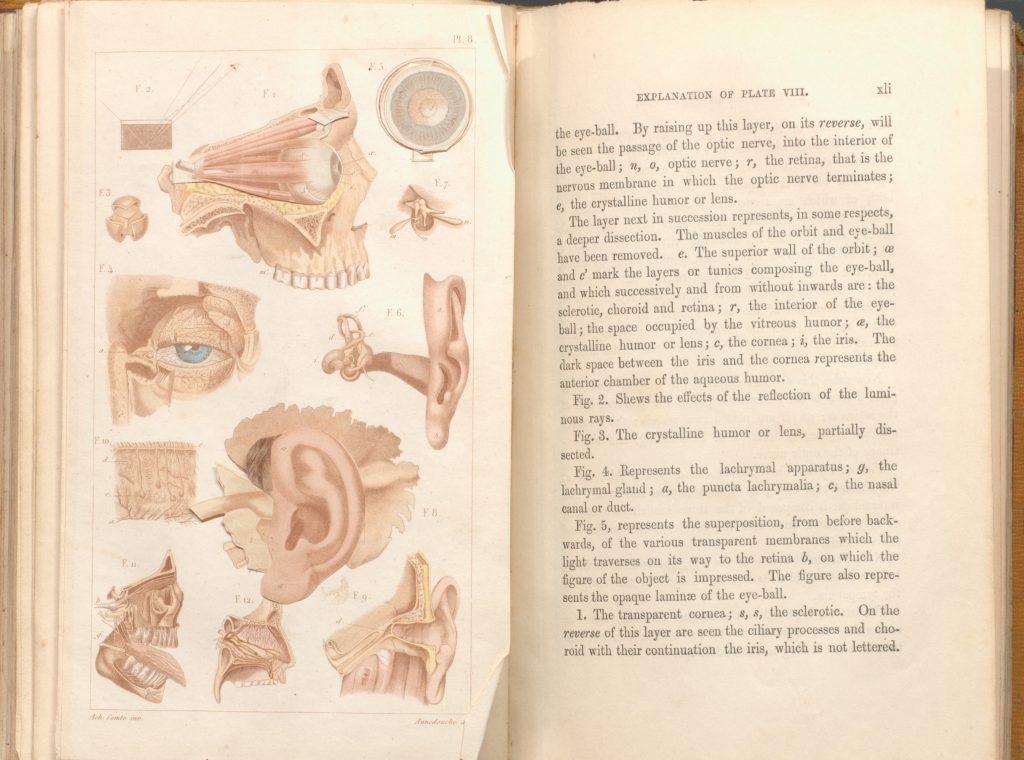

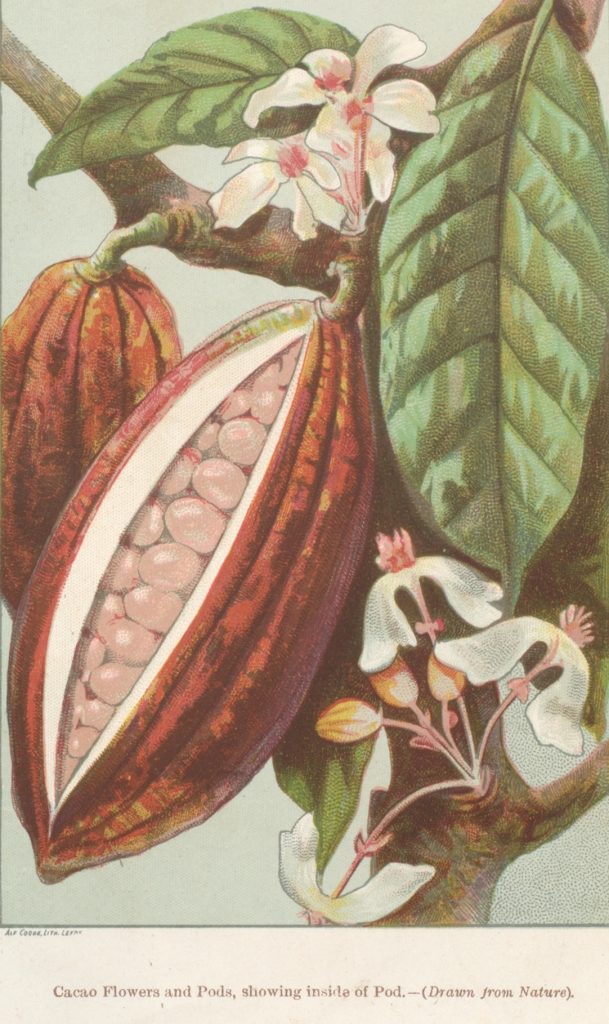

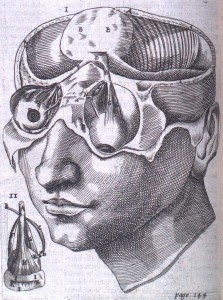

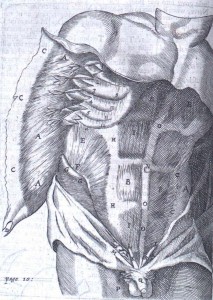

SB: One of the most striking images in the Osler Library’s collection is the “The Flayed Angel” from an eighteenth-century medical atlas by French anatomist and printmaker Jacques Fabien Gautier D’Agoty (c.1716-1785). In this richly coloured mezzotint, a woman’s back skin is peeled away to reveal the inner anatomy of her spine and the musculature of her back. The idea of slicing and paring a portion of the body’s outer boundary led us to question how skin has been conceived as the interface between the body’s depths and surface. Although D’Agoty’s fascinating picture was at the starting point of our thinking process, eighteenth-century mezzotints and prints will (unfortunately!) have to wait for another exhibition. As specialists in nineteenth-century French art and because we knew we could display wonderful wax moulages of skin diseases from the Maude Abbott Medical Museum, we wanted to work within the scope of that century. Moreover, it’s a time when dermatology emerged as a specialized branch of medicine concerned with visualizing and diagnosing skin. Once we began to explore the vast and varied nineteenth-century materials on skin from the Osler collection, it became clear that images had played a significant role in disseminating ideas on what doctors and beauty specialists considered to be normal and healthy skin ―and thus how to diagnose skin diseases and other epidermal conditions. Indeed the authors of many of the medical texts on display in the exhibition stated that medical images were indispensable to teaching doctors how to correctly scrutinize the surface of the body. I was especially interested in why several doctors included the superficial alteration of skin pigmentation in their treatises on skin diseases. In Élie Chatelain’s Précis iconographique des maladies de la peau from 1893, the doctor provided little in the way of an explanation for the cause of vitiligo, and even less for its treatment. Yet Chatelain included a hand-painted photograph that highlights the difference between a male patient’s skin colour and patches of depleted pigment that emerged on his arms, shoulders, torso, and groin. Because of, and due to, the emphasis put on the visible aspects of skin diseases, we hope that visitors at the Osler Library will see how images were part of a medical discourse that considered changes in skin colour, for example, to be a pathological feature. By examining the medical images on display, we hope to raise larger questions about the place of medical discourse in debates about race, class, and gender in nineteenth-century society.

SC: Originally, the exhibition was scheduled to open a year ago to coincide with a guest lecture by Dr. Mechthild Fend, an art historian interested in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century representations of the body, titled “Body to Body: The Dermatological Wax Moulage as Indexical Image.” Although we were unable to move forward with the project until the Osler reopened this year, Dr. Hunter encouraged us to build from Dr. Fend’s scholarship. In doing so, we explored how art historians can profit from medical collections by analyzing depictions of skin from a humanistic perspective.

First and foremost, the availability of material at the Osler guided the scope and trajectory of the exhibition. After agreeing on the representation of epidermis in modernity as the unifying thematic of the display, I began to think about how artists depicted skin. Rather than represent individual abnormalities or eccentricities, artists historically idealized features. With this in mind, I began consulting medical atlases, scientific texts, and cosmetic handbooks with an eye toward issues of beauty and idealization, aging, and birthmarks. Tying together these themes was the ways in which abstract notions of comeliness and what constitutes comeliness shaped the representational strategies used to display “superficial” medical features. I was curious about how physicians attempted to rationalize imperfections, such as wrinkles and birthmarks, as well as how scientific “facts” lent supposedly scientific support to cosmetic “knowledge.” Likewise, I was interested in how the rationalization of imperfection often defied the well-known expression: “beauty is only skin deep.” For instance, the physiognomic study of wrinkles connected the appearance of skin to the deepest recesses of the mind.

AD: Could you describe your curatorial vision or approach to the exhibition? What have you hoped to achieve?

SB: As art historians, a consideration of how skin has been depicted in paintings that are then reproduced in beauty manuals, how skin and the diseases, blemishes, or creases that can mark it have been moulded into wax, photographed or drawn, led us to question how skin has been historically conceived. This is also why we chose to look at a diverse range of materials: treatises on hygiene, beauty manuals, as well as atlases and guides for professional medical practitioners. We believe that this allows us to explore the wider historical and social contexts in which medical knowledge on skin developed. We also hope that visitors will be able to explore the historical roots for the ongoing pressure and pursuit to have smooth and evenly pigmented skin.

SC: As previously mentioned, the broader aim of this exhibition was to convey how art historians can use medical collections. Personally, I hoped to convey the importance of interdisciplinary research to an audience with diverse backgrounds without compromising the complexity of academic scholarship. Several art historians use interdisciplinary research to highlight how other disciplines, such as medicine, shaped artistic production. I sought–and in my dissertation will continue–to do the reverse. I aim to establish how art shapes the way other disciplines have understood and continue to understand their practice. In the case of early dermatology, the most obvious manifestation of this is that physicians often hired illustrators trained in the fine arts and with particular conventions to represent case studies.

AD: What sorts of other exhibition experiences have you had or been involved in? Have you found there to be particular considerations or challenges involved in working with rare books?

SB: During my undergraduate degree in History at the University of Winnipeg I had the opportunity to intern as a curatorial assistant at the Buhler Gallery, a unique gallery located in the Saint-Boniface Hospital that aims to provide a restful and contemplative space for visitors. While interning there I helped to curate an exhibition of two Winnipeg painters, Arthur Adamson and George Swinton, entitled Marking the Message. Before starting my MA at McGill I also worked as an Art Handler Technician at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. As far as organizing and installing exhibitions, I’m used to dealing with paintings and sculptures in conventional gallery spaces. Installing the exhibition at the Osler Library presented the special challenge of how to best display the images in delicate books. On the one hand, I’m used to handling the material at the Osler Library because of extensive research on a variety of nineteenth-century topics such as serum therapy, vaccination, diphtheria, rabies, breast feeding, and theories of degeneration. For an exhibition, however, we needed to consider how to best keep the books safely open for the duration of the exhibition. This is where the expertise of the staff was a necessary part of the process (thank you Anna, Bozena, Lily, and Chris!).

SC: I have been privileged to conduct research as an intern at several museums including The Museum of Modern Art, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, the Carnegie Museum of Art, the University Art Gallery at the University of Pittsburgh, and at the American Jewish Museum of Pittsburgh. These experiences offered invaluable insight into the nature of curatorial research and exhibition planning, as well as how to handle art objects. Building from my work as an intern, I’ve also been privileged to curate two exhibitions at Parsons The New School for Design titled Cultural Constructs (July 15-August 1, 2013) and (Sub)contracted (July 14-July 28, 2012). Each show featured work by candidates and recent recipients of a Master of Fine Arts in photography at Tyler School of Art, Temple University. Cultural Constructs explored the representational conventions associated with cultural heritage in the contemporary moment. This show questioned the ideological assumptions determining which architectural structures, monuments, and landscapes embody or define a culture and its history. Distinct from this exhibition, (Sub)Contracted tied together the work by five artists who adopt the visual conventions associated with photography’s earliest utilitarian uses. By documenting sculptures and capturing aerial landscape photographs, for instance, their work recalls photography’s first status as a “hand-maiden” to the fine arts and sciences. Working with rare books posed new and exciting challenges for me. Because so many of the texts housed by the Osler are illustrated, the collection offers an overwhelming amount of images from which to work! Along with this, rare books pose curatorial problems in so far as they need to be exhibited in cases. Showcases qualify the physical proximity between viewers and the objects, limiting the viewer’s ability to see the images clearly. This, coupled with the fact that it was impossible to adopt exhibition practices traditionally used in art museums to highlight formal properties or details, such as changing the wall color, curators using this space are required to think creatively about how to exhibit these materials. For instance, in the section on birthmarks, the addition of a bright red cloth highlighted the intricate colors used to represent angiomas and vascular naevus. Rare books also confound the pervasive method of organizing art works chronologically in exhibitions. Because so many of the books are reprinted in different editions over the course of several years, it proved to be easiest to think about the representation of skin thematically as opposed to chronologically. Admittedly, I felt self-conscious about the curatorial process because I am a teaching assistant to a course in which students were required to examine how exhibition practices, such as the way works are organized and hung on the wall, shape the viewer’s interpretation of the show! In many respects, we tried to highlight the “look” or aesthetic of older libraries.

Thank you, Shana and Sylvie! On the Surface/Skin Deep will run through July in the Osler Library exhibition space on the 3rd floor of the McIntyre Medical Building, 3655 Promenade-Sir-William-Osler.

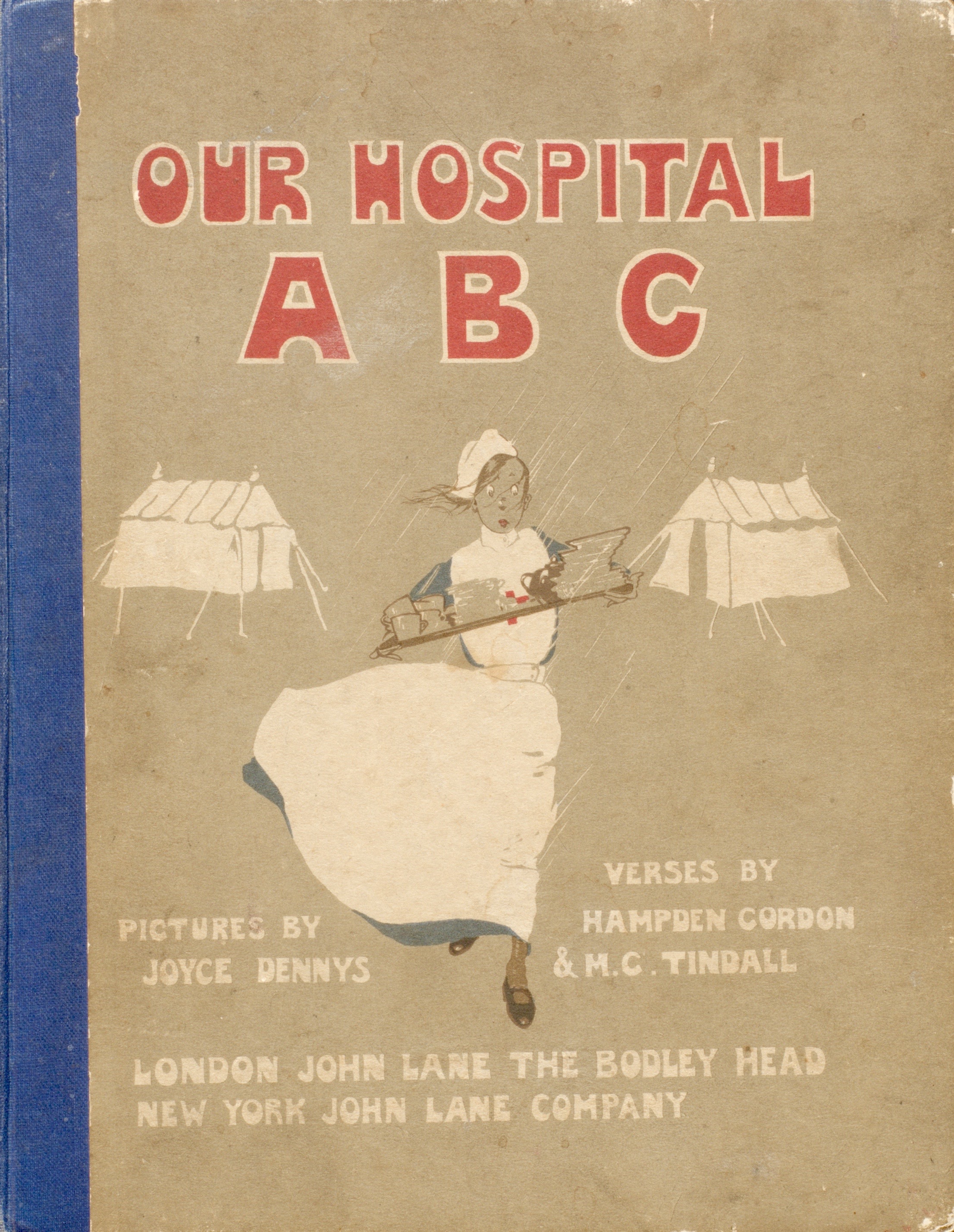

On November 11th, we remember.

On November 11th, we remember.