Please note that the Osler Library reading room will be closed for a special event this morning from 9:00-12:00. You can still access our circulating books and journal collection by the staircase in the Life Sciences Library.

Thanks!

U.S. government shutdown’s impact on medical databases

A quick note for users of PubMed and MEDLINE: both are available, but indexing for MEDLINE has ceased until the government reopens, which means that new articles are not being added.

Here is the official statement regarding MEDLINE:

Due to the lapse in US Government funding, Ovid Medline is not receiving any record or data updates until further notice.

The latest update to Ovid MEDLINE(R) was October 2, 2013. AutoAlerts scheduled for October 9, 2013 will be sent. The updates included the following:

• Ovid MEDLINE(R) Corrections

• Ovid OLDMEDLINE(R) <1946 to 1965>

• Ovid MEDLINE(R) <2009 to September Week 4 2013>

The latest update to Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations was October 1, 2013. Staff and students who use AutoAlerts and saved searches for Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations will not receive new alerts. Once Ovid receives new data from the National Library of Medicine, you may see larger than normal updates (additions & revised records).

Here is a useful list of the status of various U.S. government information services (including Center for Disease Control Reports, PubMed/NCBI, ClinicalTrials.gov, etc.) compiled and being updated by librarian Alisha Miles.

Osler Library Guide: Almanacs

This is part of a series of posts designed to expose readers to the range of materials we have here at the Osler Library and provide tips on how to find and use specific resources. These various installments will form the basis of a comprehensive Osler Library user guide. Your questions and feedback are welcome!

About

The Osler Library has a large collection of medical almanacs, for which we are still actively acquiring. The almanacs date from 1840 to 1977, with the largest number of holdings falling between 1900 and 1925. The almanac is an old genre of ephemeral—temporary or non-durable publications—that traces its history to the medieval period. These popular  items originally consisted of calendars with events, religious holidays, moon phases, and astronomical tables that provided an outlook on the upcoming year. Medical almanacs in particular were an important facet of premodern medicine as doctors took astrological information into consideration in the diagnosis and treatment of their patients. By the mid-18th century in the US and towards the end of the 18th century in Canada, almanacs were popular household books that provided health and home tips along with calendrical features. As such, they are an important source of information on lay medical culture.

items originally consisted of calendars with events, religious holidays, moon phases, and astronomical tables that provided an outlook on the upcoming year. Medical almanacs in particular were an important facet of premodern medicine as doctors took astrological information into consideration in the diagnosis and treatment of their patients. By the mid-18th century in the US and towards the end of the 18th century in Canada, almanacs were popular household books that provided health and home tips along with calendrical features. As such, they are an important source of information on lay medical culture.

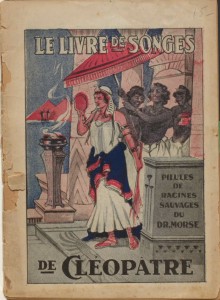

The majority of our almanacs are published in Canada, the oldest of which is Le livre de songes de Cléopâtre (Cleopatra’s book of dreams), published in French in Brocktown, Ontario, and Morristown, New York, sometime between the years 1857 and 1881. The oldest almanacs are American, such as The phrenological almanac for 1841, published in 1840. British almanacs make up a much smaller subset, with a few almanacs published

simultaneously in Canada and the U.K. and a couple homeopathic tractates from the 1970s. The majority of the almanacs in the collection are what is known as patent medicine almanacs, used by drug manufacturers as an advertising medium. Nearly 200 of the almanacs were originally purchased from a Montreal collector and acquisitions are ongoing.

Finding information

Our medical almanacs can be located through the McGill online library catalogue. The almanacs have historically been kept in a separate database, accessible through this website. The database is now no longer updated and new accruals are being catalogued in the McGill Library catalogue. Most of the almanacs that were previously only findable through the Almanacs database have now been added to the McGill catalogue as well.

An easy way to find almanacs in the library catalogue is by using the Classic Catalogue (also linked to on the library homepage) and the name of Almanac Collection, Osler Library. Once in the Classic Catalogue, you can select an Advanced Search, which will give you the option of selecting either “Advanced,” “Expert,” or “Browse.” Select the “Browse” tab and enter in the name of the collection (inside quotation marks to indicate it is a phrase): “Almanac collection, Osler Library.” Click on the link to the collection that should appear on the top of the list. Once you are inside this list of almanacs, it is possible to modify your search by using the “Limit Results” function (accessed through the pink button above the results listing). From here, you can pare down the list of almanacs by entering a keyword, date range, year of publication, or language.

General information

The almanacs may be used by in-house visitors only. Researchers are welcome during our opening hours. It’s recommended to make an appointment, but not necessary. You will be asked to leave coats and bags in our coatroom, fill out a form with your information, and leave a student card or other piece of identity with us during the time that you’re consulting materials. Only pencils can be taken into our reading rooms and staff will instruct you on proper handling of fragile materials.

Happy researching!

Further reading

Thomas A. Horrocks, Popular print and popular medicine: almanacs and health advice in early America. Amherst, MA: Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 2008.

Time, tide, and tonics: the patent medicine almanac in America. National Library of Medicine online exhibition.

John B. Blake, “From Buchan to Fishbein: the literature of domestic medicine.” In Guenter B. Risse, Ronald L. Numbers, and Judith Walzer Leavitt, eds., Medicine without doctors: home health care in American history, 11-30. New York: Science History Publications, 1977.

Elizabeth Hulse, “Almanacs.” The Canadian Encyclopedia

Osler Library FAQs

Welcome back! As an introduction, or reintroduction, to your friendly, neighborhood history of medicine library, here are some questions I get asked frequently in the tours and classes I do here in the library. I’ve answered them here for your enjoyment and edification!

Do people actually use the books here?

Absolutely! We have lots of readers come in to consult our rare books and archives, from various levels and fields. Many McGill profs use our collections in their research and McGill students use them for theses and research projects. We also receive visiting scholars from all over, some of whom are winners of our travel grants. You are not required to show academic credentials to use our collection, but if you are unused to working with fragile rare items, we will instruct you in how to use them in a way that doesn’t damage the books and contribute to their deterioration. Please feel free to write to us about your research project and make an appointment to consult our materials.

Absolutely! We have lots of readers come in to consult our rare books and archives, from various levels and fields. Many McGill profs use our collections in their research and McGill students use them for theses and research projects. We also receive visiting scholars from all over, some of whom are winners of our travel grants. You are not required to show academic credentials to use our collection, but if you are unused to working with fragile rare items, we will instruct you in how to use them in a way that doesn’t damage the books and contribute to their deterioration. Please feel free to write to us about your research project and make an appointment to consult our materials.

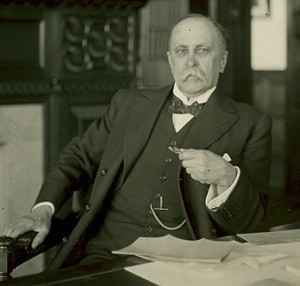

How did William Osler manage to collect all these books? Was he ridiculously wealthy?

From the William Osler Photo Collection.

Osler was a successful doctor, but certainly didn’t have the means it would take to accumulate a comparable collection today. 19th century physicians were generally paid according to what we would call a sliding scale. And since Osler was a famous physician in his day (he wrote one of the most famous medical textbooks), he had many well-to-do patients who remunerated him accordingly. Still, his love of books was so overwhelming that he describes in letters borrowing money from a rich brother to pay for his habit. Beyond that, though, the end of the 19th century and before WWI was something of a golden age for book collectors—rare books were still pricey items, but not nearly as expensive as they are today.

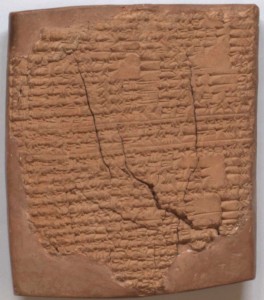

What is your oldest book?

Our oldest “book” is actually a clay tablet, probably written sometime during the 8th century BCE in Assyria (an ancient kingdom in modern day Iraq). The tablet is an example of one of the earliest forms of writing, done by forming tablets out of clay, impressing letters into them with a sharpened stick (called a stylus) in an alphabet called cuneiform, and letting the tablets bake in the sun so the writing is fixed. This tablet lists medical recipes made out of plants and animals. Here’s one particularly appealing example, a treatment for eye problems: “slay a scorpion, pull out its tongue, cut off its head, and with its blood anoint the inflamed eye; [the patient] will live.”

What is your most expensive book?

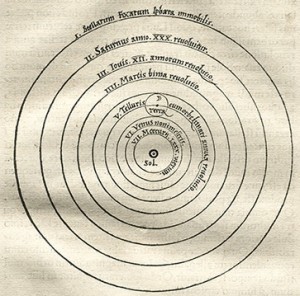

Copernicus (1473-1543), De Revolutionibus orbium coelestium (The Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), Nuremberg, 1543. B.O. 566. Woodcut f.9v depicting the heliocentric model.

It’s hard to say exactly, but this might be a contender: have a look at what this first edition copy of Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres sold for at auction last year. We also have a first edition of this 1543 work in which Nicolaus Copernicus, the famous Polish Renaissance astronomer, describes for the first time in modern history the revolution of the planets around the earth. The Ptolemaic, or geocentric, model of the universe that dominated scientific had by the Renaissance period become extremely mathematically complicated in order to explain the movement of the planets that had been observed and recorded for generations. In this book, Copernicus demonstrated that his heliocentric model could simply and elegantly explain planetary motion.

Why is there one window in the stained glass that is different from the others?

Good question! This window was designed along with the rest of the Osler Room by Montreal architect Percy Nobbs in the 1920s. It features two symbols with medical significance. First is the staff of Asclepius, the Greek patron god of medicine. Asclepius was thought to be a son of Apollo. Temples to Asclepius were found throughout the classical world, and sick petitioners would visit them to sacrifice to the god, spend the night in the temple’s inner sanctum, and receive ritual healing from the temple priests. The symbol’s serpent and staff are thought to represent healing and rejuvenation. The second symbol is a book held out by a heavenly hand. The book represents the university, learning, scholarship, and the idea of medicine as knowledge transmitted through the ages. So why is there one book that has no writing on it? What do you think: mistake or message?

Why aren’t you wearing white gloves?

Generally, it’s no longer the accepted practice in the rare books world to wear white gloves when handling materials, except in some particular cases (like delicate photographs). The theory behind gloves was that the natural oils on peoples’ fingers would wear down the books over time. This may be true (we still try to avoid touching the written and printed text itself and only touch the blank margins of a book’s pages), but it’s counterbalanced by the fact that pages are a lot harder to turn in bulky gloves and the risks of tearing a page are a lot higher. Better to just come with clean hands.

Generally, it’s no longer the accepted practice in the rare books world to wear white gloves when handling materials, except in some particular cases (like delicate photographs). The theory behind gloves was that the natural oils on peoples’ fingers would wear down the books over time. This may be true (we still try to avoid touching the written and printed text itself and only touch the blank margins of a book’s pages), but it’s counterbalanced by the fact that pages are a lot harder to turn in bulky gloves and the risks of tearing a page are a lot higher. Better to just come with clean hands.

Are Osler’s ashes really there?

Yes. But no, sadly, you can’t see them.

Upcoming Osler tours

As part of the university’s orientation activities for the new school year, we’ll be offering two tours of the library next week on Tuesday and Wednesday. Come and get a peek at Osler’s treasures and learn about using the library.

Tuesday, August 27th, 3:30pm

Wednesday, August 28th, 4:00pm

The Osler Library is on the 3rd floor of the McIntyre Medical Building, 3655 promenade Sir William Osler. Tours will begin in the exhibition area.

To find out about other library tours and workshops, have a look here.

A Look into the Osler Library Artifact Collection

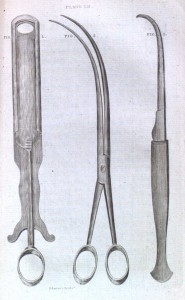

This tonsil guillotine (otherwise known as a tonsillotome) is one of hundreds of relics of the history of medicine housed in the Osler Library artifact collection.

Developed in the decades following the French Revolution, the tonsil guillotine has one glaring similarity to its much more sinister cousin: a sharp, fast-moving blade designed to cut the afflicted mass from its bulk. This much smaller blade is fastened in between two fixed steel plates, and attached to a moveable handle that slides it through an auxiliary ring intended to fit around the infected tonsil.

The instrument was originally developed as an adaptation to Benjamin Bell’s (1749-1806) uvulotome, which was similarly used to excise an inflamed and elongated uvula. Bell describes the use of this tool in his System of Surgery, “that part of the uvula intended to be removed being passed thro the opening of the body of the instrument, the cutting slider, which ought to be very sharp, must be pressed forward with sufficient firmness for dividing it from the parts above.”

Instruments for removing the uvula and small tumors from the throat, from Benjamin Bell’s System of Surgery. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: C. Elliot & T. Kay, 1789.

The physician Philip Syng Physick (1768-1837) used this same device in treating a patient with a relentless cough in the spring of 1826. After noting the patient’s elongated uvula, Physick followed a popular treatment that involved partly removing the infected area. Up until that point, he, among other physicians, had used scissors or ligatures for such operations. Dr. Physick instead decided to try an old instrument in order to make the process easier. His design was very similar to that of Bell’s uvulotome: a sharp sliding blade would pass through two plates into a round opening at the end of the instrument to remove the uvula in one smooth motion. In subsequent years Physick adapted this instrument for use in excising infected tonsils, enlarging the aperture of the ring and making slight modifications to the steel body. The guillotine in our artifact collection follows Physick’s early design of a pointed and movable cutting blade between two steel plates. On one end of the device is a bone handle and ring used to position and slide the blade within the patient’s mouth. The steel hoop at the opposite end of the instrument may have been covered by a strip of wax linen to achieve a cleaner cut, and the thin needle lying flat above the blade would have kept the infected tonsil in place during the operation.

At this time, tonsillectomies were considerably restricted by inadequate anesthetic, so surgeons made every effort to perform the operation as quickly as possible. This is perhaps why the guillotine became a popular tool for the operation; contemporary alternatives involved the use of curved scissors (which often led to excessive hemorrhaging) or the use of a wire ligature to slowly separate the tonsil from the inside of the mouth (a long and excruciating process without viable painkillers). In contrast, the guillotine could perform the excision in one even movement.

At this time, tonsillectomies were considerably restricted by inadequate anesthetic, so surgeons made every effort to perform the operation as quickly as possible. This is perhaps why the guillotine became a popular tool for the operation; contemporary alternatives involved the use of curved scissors (which often led to excessive hemorrhaging) or the use of a wire ligature to slowly separate the tonsil from the inside of the mouth (a long and excruciating process without viable painkillers). In contrast, the guillotine could perform the excision in one even movement.

Further modifications of the tonsil guillotine were made by Morel Mackenzie in the 1860s, popularizing the instrument for wider use. It remained the preferred method for tonsillectomy until the early twentieth century, until it became more common to perform complete rather than partial removal of the tonsil. A technique involving removal of the tonsil with a scalpel and forceps proved much more effective and precise, and tonsillectomy using the guillotine eventually fell out of favor with most physicians.

References

Benjamin Bell. A System of Surgery. Edinburgh: C. Elliot & T. Kay, 1789.

J. Mathews, J. Lancaster, I. Sherman, and G. O. Sullivan. “Guillotine tonsillectomy: a glimpse into its history and current status in the United Kingdom.” The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 116 (Dec. 2002): 988–991.

Neil G. McGuire. “A method of guillotine tonsillectomy with an historical review.” The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 81, no. 2 (Feb. 1967): 187-195.

Ronald Alastair McNeill. “A History of Tonsillectomy: Two Millenia of Trauma, Haemorrhage and Controversy.” The Ulster Medical Journal 29, no. 1 (June 1960): 59-63.

Philip Syng Physick. “Case of Obstinate Cough, occasioned by elongation of the Uvula, in which a portion of that organ was cut off, with a description of the instrument employed for that purpose, and also for excision of scirrhous tonsils.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 1, no. 2 (1828): 262-265.

Final chance to see Designing Doctors exhibit

Designing Doctors, an exhibition curated by Prof. Annmarie Adams highlighting the contributions of physicians to hospital architecture is on through August. Come and see it now if you haven’t yet had a chance! In the Osler Library lobby, 3rd floor of McIntyre Medical Building, 3655 promenade Sir William Osler.

Designing Doctors showcases the Osler Library’s outstanding collection of architectural advice literature on hospital architecture. Its focus is on the development of the so-called pavilion-plan hospital, a ubiquitous typology for hospitals in the English-speaking world in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries which maximized ventilation and daylight; their signature detail, however, was the Nightingale ward, a large, open space which typically housed about thirty patients.

Two sub-themes shape the organization of the exhibition: the role of physicians in the design of pavilion-plan hospitals and the position of hospitals as tourist destinations. Consequently, Designing Doctors presents a series of classic books written by doctor-architect teams or physicians who saw themselves as architectural experts. Several of these books are dedicated by or to famous figures, including Florence Nightingale, Henry Saxon Snell, and Edward Fletcher Stevens. Included here too are delightful souvenir items featuring hospital imagery: an inkwell, a soup bowl, hospital postcards, and a humorous board game as reminders of the wide reach of hospital architecture images in twentieth-century popular culture.

The exhibition is curated by Professor Annmarie Adams, Director of the School of Architecture, McGill University, and member of the Osler Library’s Board of Curators.

Osler Fellows Library

The Osler Fellowship is programme run by the Office of Physicianship Curriculum Development. The fellows are members of the medical faculty who work with students to encourage them reflect on the role of the doctor as healer and professional. They also happen to be very well read! We have a number of books given to the library by Osler Fellows touching on many different areas of medical humanities. You can see their book recommendations by using the list function in McGill’s WorldCat catalogue.

First, enter the WorldCat catalogue from the library homepage.

Then on the next page, click on “Search for Lists” on the drop-down box under “Search.”

Search for “Osler Fellows Library” and voila! You can even read in the catalogue what the fellows have to say about why they chose a particular book. Most of the books are held in the Osler Library, some in other libraries, but just note that those held in Life Sciences are currently unavailable.

P.S. Anybody can make a list of resources in the WorldCat catalogue. Need to keep track of course readings? Have some great sci fi recommendations to share? Check out this YouTube video that shows you how to create lists. (The look and feel of the catalogue here are McGill, are slightly different than in the video, but the actions are the same.)

Bartholinus Anatomy

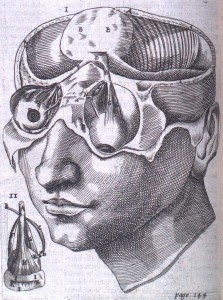

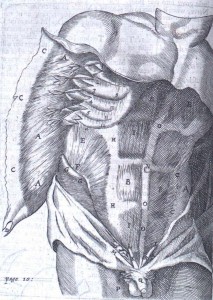

Born into a Danish family of physicians, Thomas Bartholin (1616-1680) was influenced at an early age by his relatives’ forays into anatomical science and medicine. He traveled widely throughout Europe before receiving his medical degree at Basel in 1645, and subsequently made significant contributions to 17th century anatomical knowledge, particularly concerning the discovery of the lymph vessel system as well as first recognizing the thoracic duct in humans. A prolific writer, his work was published both in Leiden and London and translated into several different languages. Like his father, Caspar Bartholin the Elder, Thomas wrote several anatomical treatises which became rather popular textbooks. This 1668 English translation of his most famous work, Bartholinus Anatomy, has recently made its way into the Osler Library. Published in London by Nicholas Culpeper and Abdiah Cole, the anatomical treatise contains 153 copperplate engravings (4 of which are fold-out plates).

The text is a later adaptation of his father’s Anatomicae Institutiones Corporis Humani (1611), which was, for many years, a standard textbook on the subject of anatomy. Caspar’s work was revised and illustrated by Thomas who published the new edition, Anatomia, in 1641. Following his observations on the human lymphatic system (along with some criticism from fellow anatomists) Bartholin updated his Anatomia, publishing a revised and augmented edition in 1655.

The younger Bartholin’s textbook differs from that of his father with the addition of references to the writings of contemporary anatomists, such as William Harvey and Gasparo Aselli. The work of these two physicians is explicitly referenced in the book’s appendix: two letters from Johannes Walaeus to the author, “Concerning the Motion of the Chyle and Blood” and “Of the Motion of the Blood.” The accompanying illustrations likewise updated the original edition. These engraved plates, roughly inserted within and often overlapping the book’s text, supplement Bartholin’s discussion of the human body. Most of these images were not original, but rather were based on the work of Vesalius, Casserio, Vesling, and other famous anatomists.

Bartholin’s Anatomy was one of the most popular anatomical texts of the 17th century. Separated into four books and four “petty books” detailing distinct sections and systems of the human body, the exhaustive work was central to the early modern study and development of the anatomical sciences.

Digital exhibition sneak preview, part 3

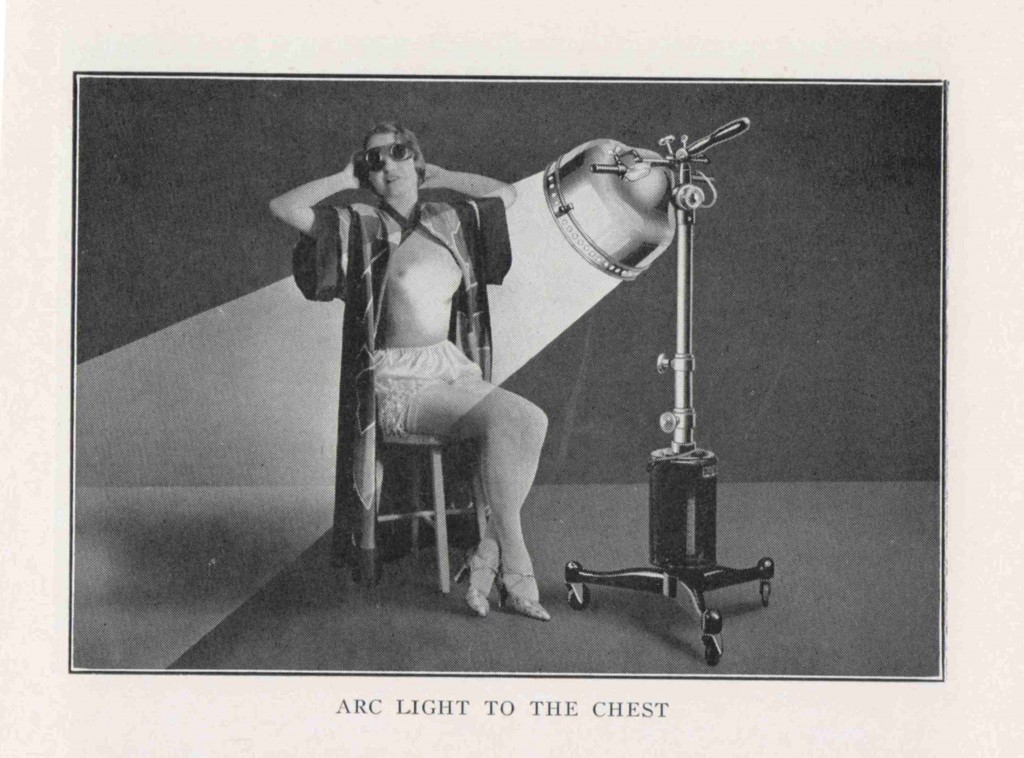

Missed our 2011 exhibition “Our Friend, the Sun: Images of Light Therapeutics, 1901-1944”? Here’s a sneak preview of the digital exhibition currently under construction. You can find the full exhibition catalogue by curator Dr. Tania Anne Woloshyn here. And stay tuned for more!

John Harvey Kellogg. Light therapeutics: a practical manual of phototherapy for the student and the practitioner. 2nd ed. Battle Creek, Mich. : Modern Medicine Pub. Co., 1927.

Remember our long-suffering patient from last week? Contrast that with this week’s gleeful recipient of light therapy. By the 1920s, physicians began incorporating advertising imagery into their textbooks. In this photomontage, we are presented with a fresh-faced, smiling model, coiffed in the latest 1920s crop. The impression is that this phototherapeutic treatment is neither uncomfortable nor distressing, but in fact an enjoyable process. The ambiguity of her surroundings, reminiscent of a photographer’s studio, is heightened by the impossibilities of the scene: the rays of the lamp (which itself appears hand drawn) shine on her chest and yet continue undisturbed beyond her.

Further reading

Simon Carter. Rise and Shine: Sunlight, Technology, and Health. New York: Berg, 2007.

Tania Anne Woloshyn, “‘Kissed by the Sun’: Tanning the Skin of the Sick with Light Therapeutics, c.1890–1930,” in Kevin Siena and Jonathan Reinarz, eds. A Medical History of Skin: Scratching the Surface (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2013), chap. 12.